Two independent but intertwined strategies have had incredible success in keeping a small country’s people in far better shape in coping with COVID-19 than its huge neighbors and many rich countries. I am speaking of the tiny Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan, wedged in by China and India. By pursuing a health requirement that its entire child and adult population be vaccinated against Measles, Mumps and Rubella (MMR), and opting to adopt a One Health Strategy, Bhutan is a place much of the world can learn from.

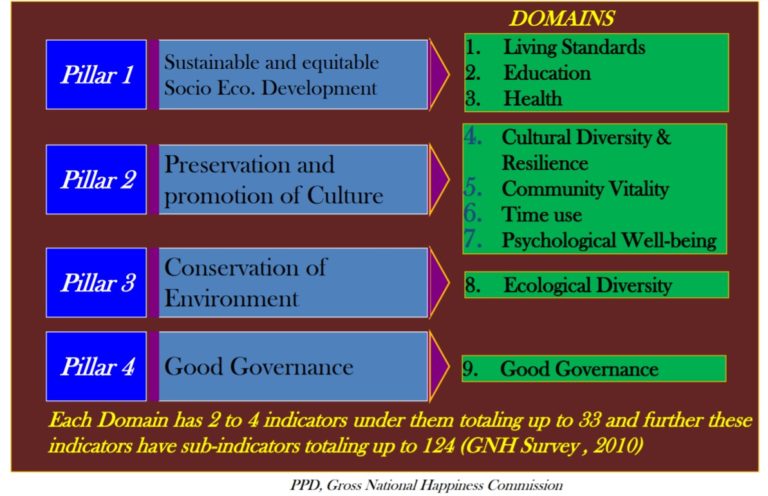

Bhutan is widely known as the creator of the “Gross National Happiness Index”, with GNH replacing Gross National Product as its priority indicator. A single number index was developed with the help of Oxford University scholars from 33 indicators under nine domains. Despite continuing high levels of poverty, Bhutan is a country found among the top in terms of “happiness” – much higher than its level of poverty would predict and systematically divergent from the ranking given to it by the UN-founded World Happiness Index (that was inspired by Bhutan’s GNH). No doubt as a result of a different definition of happiness.

Bhutan’s roughly 800,000 people have been the beneficiaries of a constitutional monarchy with a King who has supported his scientific experts, politically, intellectually and operationally to garner the full support of his people.

Bhutan, which translates to “Land of the Thunder Dragon”, is a small territory landlocked between China and India, the former the origin of COVID-19, the latter rapidly becoming a country with among the world’s highest COVID-19 positive cases and deaths. On 17 July 2020, infections in India surpassed one million, making it the third country with the largest number of infected people, behind Brazil (over 2 million) and the United States (over 3.5 million).

Unlike Nepal with confirmed coronavirus-positive cases of over 17,500 (for a population of over 29 million people and much geographically and ethnically in common with Bhutan but not recent politics), Bhutan has had only 87 coronavirus cases and no deaths. Proportionately, that’s roughly six times fewer cases than Nepal. This, despite having significant trade activities with its two COVID Scylla and Charybdis neighbors.

An investigation by the World Health Organization now suggests that MMR vaccines may help protect adults over 50 from COVID-19, putting it this way:

The neuroscientists suggested vaccinating “at-risk” age groups with an MMR vaccine merits further consideration as a quick way to slow the wave of COVID-19 illnesses and death for older adults.

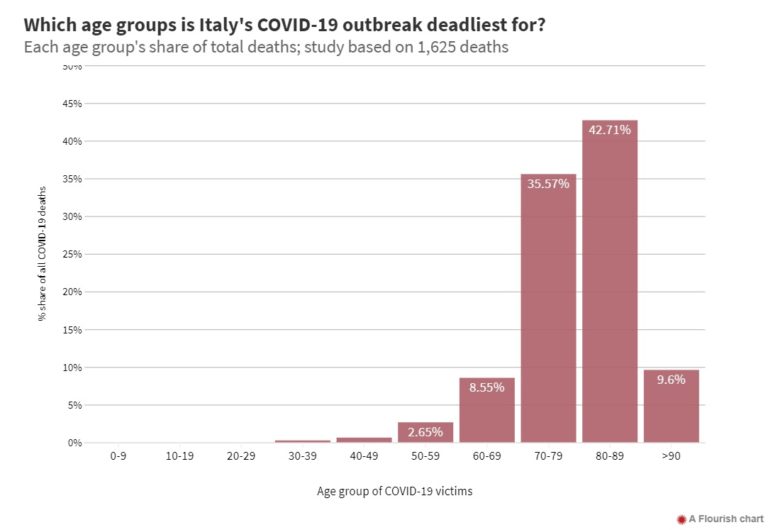

The MMR vaccine was introduced in 1971. It is given as a childhood vaccine in the U.S. and in Europe, which is why most adults over the age of 50 have not received it. But what drew the attention of the WHO is the now well-established fact that coronavirus is far more likely to kill adults over 50 years old in both the U.S. and Europe.

For example, the epicenter of the pandemic in Italy this Spring was the Lombardy region and it was found that the elderly (and immuno-compromised) were overwhelmingly the most likely to die. As this study shows:

But in countries that have created vaccination “catch up” programs where MMR vaccines are commonly given to adults, there appears to be a far lower death-rate from COVID-19.

In this respect, Bhutan stands out with zero COVID-19 deaths. The Bhutan Minister of Health, Dechen Wangmo, a graduate of the Yale School of Public Health, promulgated and implemented their MMR strategy, with support from politicians, civil servants, and ultimately the people. As a result, by the time the pandemic hit, Bhutan had vaccinated nearly its entire population of both children and adults with the MMR vaccine.

Coming second best in this race against COVID-19 is Hong Kong, almost as large as New York City, with only 4 reported deaths from the coronavirus compared to over 12,500 deaths in New York. This difference, arguably, could be due to the fact Hong Kong also has had a mass-immunization program to give MMR vaccines to everyone under 19 years old since 1997 and that it began giving out free MMR vaccines to adults in 2019 and continued doing this into 2020.

There is much further investigations to be done, and of course, any number of factors affect lower numbers of COVID cases. But a coherent national health strategy and strong health leadership is likely to be critical

Bhutan’s One Health Approach

The second strategic direction which in all likelihood has been a contributor to Bhutan’s success is that they chose to recognize the interface between human-animal-environmental health.

The need to institutionalize One Health (OH) concept was recommended during a National and Regional One Health Symposiums held in 2013 during which external experts were asked to assist the Bhutanese in designing their own OH approach.

A strategic framework and action plan were prepared a year later. Their five-year OH framework (2017 – 2021), comprises seven strategies and outlines collaborative mechanisms amongst stakeholders to prevent and control zoonotic and high-impact infectious diseases in the country.

From the outset, the Bhutan multisectoral team recognized that infectious zoonotic diseases such as rabies and highly pathogenic avian influenza caused by the H5N1 virus provided an impetus for adaptation of a One Health approach to disease management. A Bhutanese public health leader put it this way:

“If we look at Bhutan, we get so many outbreaks like rabies, avian influenza which is otherwise known as bird flu. So, when there are such outbreaks in animals, it should act as an early warning to humans.”

Pandemics have been part of human history, each dealt with in varying degrees of success. Measles was thought to be well in hand; however, it has returned with a vengeance, and not just in poor countries with weakened health systems. There was a major outbreak in the United States in 2019, and it remains a significant health risk in the South Pacific, and in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Small developing countries such as Samoa, have had a difficult time containing new measle outbreaks. On the other side of the world, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s most heavily populated countries that had fought hard to contain Ebola in Eastern Congo, had more than 6,000 measle deaths in January 2020 in that region, far outnumbering those caused by Ebola.

In principle, measles herd vaccine immunity should be achievable. In practice it often doesn’t exist– and likely when we get to a COVID vaccine, a similar challenge will have to be faced. A principal reason? Anti-vaccine movements. Such movements build on strong distrust of government at all levels, inundate populations with false information, and acting as a small vocal group, are able to persuade many to resist public health appeals.

None of these impediments were and are to be found in Bhutan. What one takes away from the Bhutan experience is that good values, sound governance, trust in science, good communications to and with the people, make all the difference in the health and well being of a people. It is a recipe others need to follow.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. In the featured photo: All-female picnic lunch, Bhutan Photo by Kandukuru Nagarjun, taken Oct ’14, Flickr