SDG16 AND THE GLOBAL EFFORT TO PREVENT VIOLENT EXTREMISM: BRIDGING THE DEVELOPMENT AND SECURITY DIVIDE

Violent extremism – here defined as support for, or perpetration of acts of, violence with the purpose of advancing a socio-political agenda – has emerged as one of the most critical global threats of our time. Preventing and countering violent extremism can be an important tool for both conflict prevention and development-based on the premise that violence impedes sustainable development, threatens security and undermines human rights.

The recently adopted Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) reflect this recognition. Among them, Goal 16 (SDG 16) on the “Promotion of Just, Peaceful and Inclusive Societies” is particularly relevant given that unmet expectations, inequality (especially aligned with ethnic or religious divisions), marginalization and human rights violations are known to be among the drivers of violent radicalization. The need for collaborative global development to prevent and counter violent extremism is also underscored by SDG 16, one of whose key targets is to “strengthen relevant national institutions, including through international cooperation, for building capacity at all levels, in particular in developing countries, to prevent violence and combat terrorism and crime”.

The pursuit of SDG 16 presents a valuable opportunity to bridge the development and security divide because efforts to prevent violent extremism constitute one avenue to pursue the achievement of peace, justice, and stronger institutions. SDG 16 explicitly provides an entry point for development and security actors to come together to promote inclusive, multi-dimensional approaches to achieving a peaceful society.

SDG 16 was established on the premise that endless cycles of conflict and violence are escapable and must be addressed. Achieving SDG 16 will require development actors to engage with security institutions, especially when operating in contexts – such as fragile and post-conflict ones – that may be particularly vulnerable to terrorism and violent extremism.

In the Photo: Burundian sniper serving with the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) is seen at daybreak on a frontline position in territory recently captured from insurgents, in Deynile District, in the northern fringes of the Somali capital Mogadishu. Photo Credit: UN Photo/Stuart Price.

The potential link between the other SDGs and preventing conflict and violent extremism objectives has been acknowledged by an increasing number governments, organizations and actors which have already identified ways of bridging security with development.

Some favor targeted preventing and countering violent extremism-specific interventions; others focus on what the UN calls “conditions conducive” to the spread of terrorism and promote preventing conflict and violent extremism relevant programs that may resemble traditional development, peace-building and conflict-management activities where preventing and countering extremist violence is a by-product rather than the primary goal.

Violent extremism constitutes both an international security and a development concern.

The link is particularly well-evidenced in areas like Central Africa and the Lake Chad Basin afflicted by both protracted (under)development and increasing radicalization. SDG 16 offers a valuable opportunity to bridge the development and security divide if adequate attention is paid to contextual factors. Recent events in these regions and elsewhere underscore the need for a focus on “peace, justice, and strong institutions” as an entry point for development and security actors to foster collaborative inclusive approaches to prevent violent extremism and promote a more peaceful and prosperous society.

THE DEVELOPMENT-SECURITY NEXUS

The Agenda 2030 is a plan of action that “seeks to strengthen universal peace in larger freedom”. The SDGs integral to this Agenda are neither legally binding nor intended to prescribe national policies, but conceived as a compass for the coordination of global efforts. As a whole, these goals aim to significantly reduce all forms of violence – both kinetic and structural – and work with governments and communities to find lasting solutions to conflict and insecurity.

Related Article: “Integrating Peace, Justice and Stronger Institutions“

It is well documented that sustainable development cannot be achieved in the absence of peace, stability, human rights and effective governance based on the rule of law. High levels of armed violence and insecurity have a destructive impact on a country’s development. They negatively affect economic growth and often result in long-standing grievances that can last for generations.

Responding to these geopolitical realities, the UN Security Council described the relationship between security and development as “closely interlinked and mutually reinforcing and key to attaining sustainable peace”, underscoring the synergy between conflict, violent extremism and development.

Furthermore, although poverty does not constitute a direct causal relationship to violent extremism and terrorism, poor countries are among the most affected by extremist violence. Broader interpretations of security – understood as “human security” which attends to environmental, economic, health and crime-related threats, as opposed to narrower views of “national security” – more clearly illustrate the synergistic overlap between preventing and countering violent extremism efforts and development assistance.

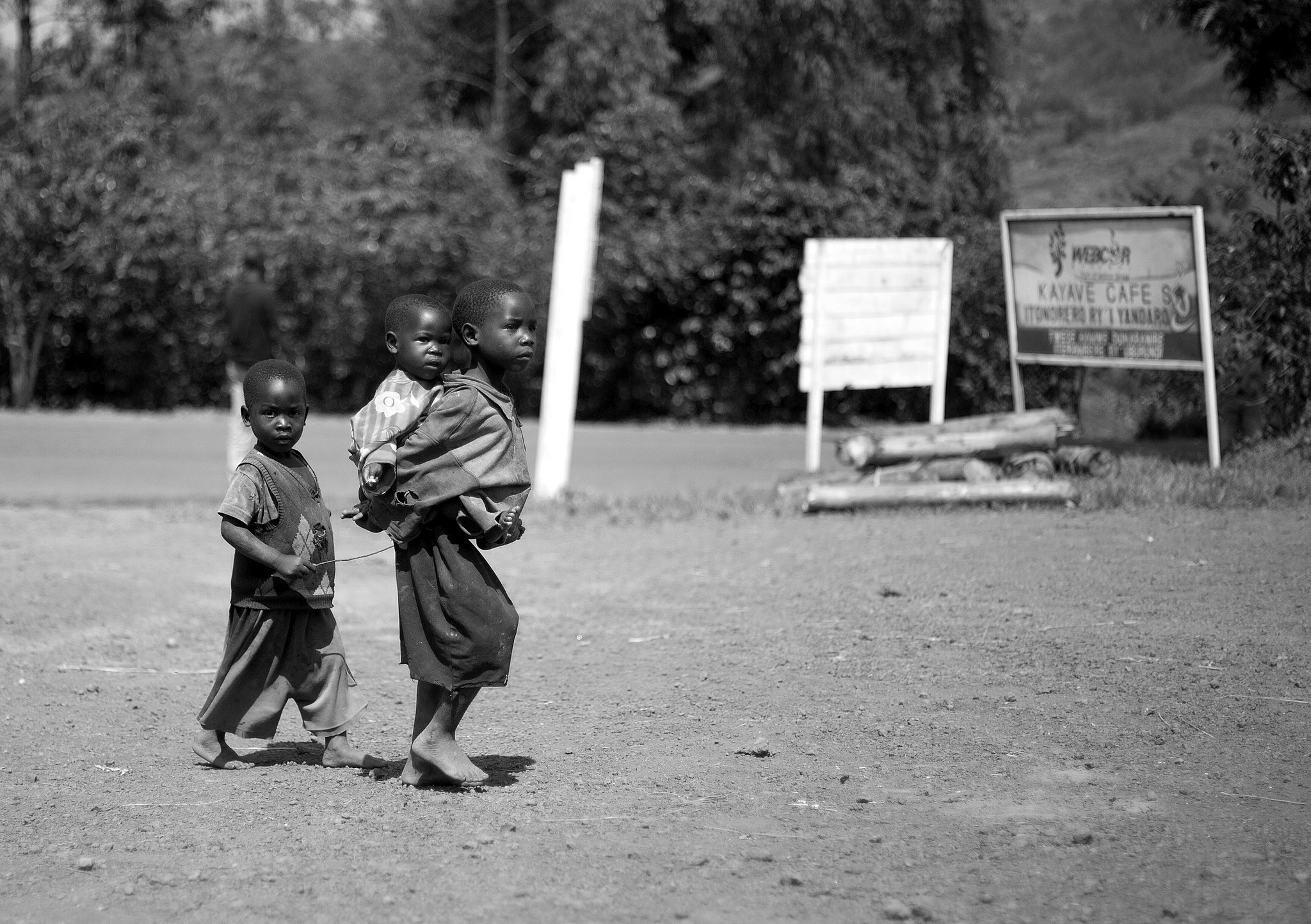

In the Photo: Burundian Kids near Butegana’s Coffee Washing Station, Kayanza, Burundi. Photo Credit: Daniel Pereira

As a case in point, the World Bank, in its World Development Report 2011, focused specifically on conflict, security, and development. This report highlighted the severe developmental consequences and human costs of conflict, arguing that violence had been the main impediment to meeting the Millennium Development Goals.

Restoring confidence and transforming the institutions that provide citizen security, justice, and employment are thus key to breaking cycles of insecurity and realizing economic development and stability.

The UN Development Programme (UNDP) offered similar conclusions in its Human Development Report 2015. In this report, the UNDP cautions that violent extremism not only deprives people of their freedoms but also limits opportunities to “expand their capabilities”. A sustained high level of insecurity has adverse consequences for the socio-economic prospects of individuals and communities and impedes the advancement of the SDGs with dire implications for terrorism and extremist violence.

As mentioned above, in January 2015, the UN Security Council had identified the nexus between security and development, expressing it as “closely interlinked and mutually reinforcing and key to attaining sustainable peace”. Further emphasizing this connection, the UN Secretary-General’s Plan of Action on Preventing Violent Extremism (PVE) made a clear association between efforts to prevent violent extremism and development, calling for the establishment of national and regional PVE action plans.

Specifically, he stated that “violent extremism aggravates perceptions of insecurity and can lead to repeated outbreaks of unrest which compromise sustained economic growth,” warning that “violent extremism threatens to reverse much of the development progress made in recent decades.” He further encouraged Member States to align their development policies with the SDGs, many of which were highlighted as critical to addressing global drivers of violent extremism and enhancing community resilience.

CASE STUDIES: AFRICAN LESSONS IN EXTREMIST VIOLENCE AND UNEQUAL DEVELOPMENT

Central Africa and the Lake Chad Basin are two of the regions where unequal development and extremist violence have increased in recent years. Between 2014 and 2016, I carried out a UNICEF-sponsored study focused on local means of conflict resolution and the determinants of social cohesion as a protective mechanism against violence and radicalization in returnee – and refugee-hosting areas of Chad and Burundi (to be published in 2018).

While historically and culturally these two countries are quite disparate, they also share notable similarities.

Their respective populations are experiencing the compounded impact of protracted crushing poverty, ethnic conflict, forced displacement and, in recent years, heightened levels or violence and radicalization.

Uprooted individuals (e.g. refugees, internally displaced and other forced migrants) have been identified as at-risk groups, vulnerable to recruitment and radicalization to violence.

This is often more the case in contexts where they are not integrated and lack human security, as the findings of my study in Chad and Burundi evidenced. It is, however, imperative to recognize that “vulnerable” or “at risk” does not imply an automatic assumption of support for or participation in extremist or other forms of violence.

The threat of radicalization and mobilization into violence can only be mitigated if comprehensive, context-specific policies are adopted and implemented that extend beyond immediate life-saving needs and address the long-term prospects of the displaced population.

A focus on the younger generations who are more likely to be negatively impacted and more vulnerable to radicalization is also paramount, as findings from this and other analyses indicate a differential targeting of youth – especially, although not exclusively, young males – for indoctrination.

In the Photo: Dr. Ensor conducting focus group discussions with religious leaders in Koumra, Chad. Photo Credit: Dr. Marisa O. Ensor

My study also shows that both vulnerability and resilience are gender and generationally-differentiated.

A shared aspect of SDG 16 and conflict and violent extremism is the recognition of the vital roles of women in both countering violent ideologies and working as peacebuilders. Security Council Resolution 2242, adopted in 2015, following the high-level review of Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, adopted in 2000, reflects this approach. So does the parallel Security Council Resolution 2250 on Youth, Peace and Security adopted in 2015, which emphasizes the importance of youth as agents of change in the maintenance and promotion of peace and security.

It is recognized that women and youth of both genders – not just adult males – play varied roles in relation to both development and violent extremism. These roles are reflected in SDG 16’s advocacy of peaceful and inclusive societies that uphold the rule of law for all.

As Dr. Alaa Murabit has posited in her recent article on gender equality as the foundation for achieving the SDGs, “women’s roles as nurturers and community builders elevate peace and security discussions and have the potential to realize SDG 16 into fruition”. Furthermore, peace agreements are estimated to be 35 percent more likely to be respected for 15 years or more when women are involved in the drafting process.

Women’s involvement in peace negotiations can make the difference in the reemergence of violence or the maintenance of peace, and must thus also be recognized as vital stakeholders in efforts to promote security and prevent violent extremism.

In the Photo: The Inbonerakure (meaning those who see far in the local Kirundi language) are a youth militia armed by Burundi’s ruling party widely believed to engage in violence for both personal and political aims. Photo Credit: Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Overcoming Challenges and Moving Forward

In the last few years, a number of initiatives have emerged under the rubric of preventing and countering violent extremism (CVE) efforts, including those concentrating on the role of youth, gender, social media, religion, education, livelihoods and security sector reform, among others. Although development and security aims can be overlapping and mutually reinforcing, there are challenges in integrating CVE objectives in stabilization and development programs.

The range of programs addressing the prevention of conflict and violent extremism suffers from a lack of conceptual clarity, an unclear scope, and underdeveloped monitoring and evaluation frameworks.

Ascertaining the success of SDG 16 in promoting just and peaceful institutions, thereby advancing development and objectives preventing conflict and violent extremism, is a challenging task as this Goal is inextricably linked to the all of other SDGs.

The most recent figures show mixed results; while homicides have slowly declined (SDG 16 target 16.1.1) and more citizens around the world have better access to justice (SDG 16 target 16.3), high-intensity conflicts and various manifestations of political violence (SDG 16 target 16.1.2) have increased in recent years.

In the Photo: Dr. Ensor visits a rehabilitation center for at risk female youth in Rumonge, Burundi. Photo Credit: Dr. Marisa O. Ensor

The cases of Chad and Burundi suggest that complex political, ethnic, and religious environments, the succession of intensified violence and subsequent waves of displacement defy simple, mono-causal links between poor development outcomes, lack of peace and security, and radicalized attitudes.

A development-heavy approach alone is unlikely to address some of the ideological and political factors that may contribute to support for violent extremism. Additionally, the long-term nature of development initiatives runs contrary to the urgency and focus on immediate gains seen as necessary to address the rapidly evolving contexts in which efforts preventing conflict and violent extremism are implemented.

Ethical concerns about the “securitization” of development and humanitarian aid, and the resulting legacy of distrust between governments and civil society, further contribute to reluctance on both sides to engage in collaborative partnerships.

…the succession of intensified violence and subsequent waves of displacement defy simple, mono-causal links between poor development outcomes, lack of peace and security, and radicalized attitudes.

The UN is well-positioned to help establish such a multi-stakeholder platform. Within the larger framework of the globally agreed upon SDGs, strengthening local institutions and political empowerment will be key to the successful implementation of SDG 16.

The hope is that this will contribute to promoting the means of addressing local grievances through a non-violent, and more inclusive process supportive of global efforts that prevent conflict and violent extremism.