HOW THE WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME USES INNOVATION TO FIGHT HUNGER

My first introduction to the United Nations and organizations such as the World Food Programme came in secondary school as a delegate for Libya at The Hague International Model United Nations. The school I attended represented Libya with the goal to further its social, economic, and development concerns as much as we could in the G2 Assembly. One highly active organization at our mock General Assembly was the school representing the World Food Programme (WFP). Their main goal seemed lofty and highly unrealistic in our given timeline: zero hunger by 2015. [1]

“Zero hunger? Why are they even trying with so many other partner organizations and delegates lobbying for fair working conditions, ensuring environmental sustainability, and maternal health?” I asked myself. I had the utmost respect for their passion, but thought indignantly that they need to break their points down into actionable solutions when presenting their proposals.

“Zero hunger,” they maintained, “is the path to equality and reaching the Millennium Development Goals. If we can eradicate hunger, we can save the world.” (Note: the Sustainable Development Goals went into effect in 2015.)

The road to zero hunger is a journey the World Food Programme has been fighting for since its founding in 1961. Originally proposed as an experiment in creating a “multilateral food aid programme” resolutions were approved to establish WFP on a three-year experimental basis within the structure of the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), historically one of the first and largest specialized UN agencies focused on rural development. In 1965, resolutions between the FAO and the UN General Assembly established WFP on a continual basis “for as long as multilateral food is found feasible and desirable.”

Today, according to the FAO, 795 million people do not have enough food to lead healthy, active lives. That is roughly one in nine people in the world. Additionally, The Lancet maintains poor nutrition has caused 45% of all of the deaths in children under five. If you break that down, it’s roughly 3.1 million children per year. Further, 66 million primary school-age children attend school hungry in the developing world. These statistics seemed to reflect what I was previously denying: if you solve hunger, you will find sustainable economic, environmental, and social changes across the world.

795 million people do not have enough food to lead healthy, active lives.

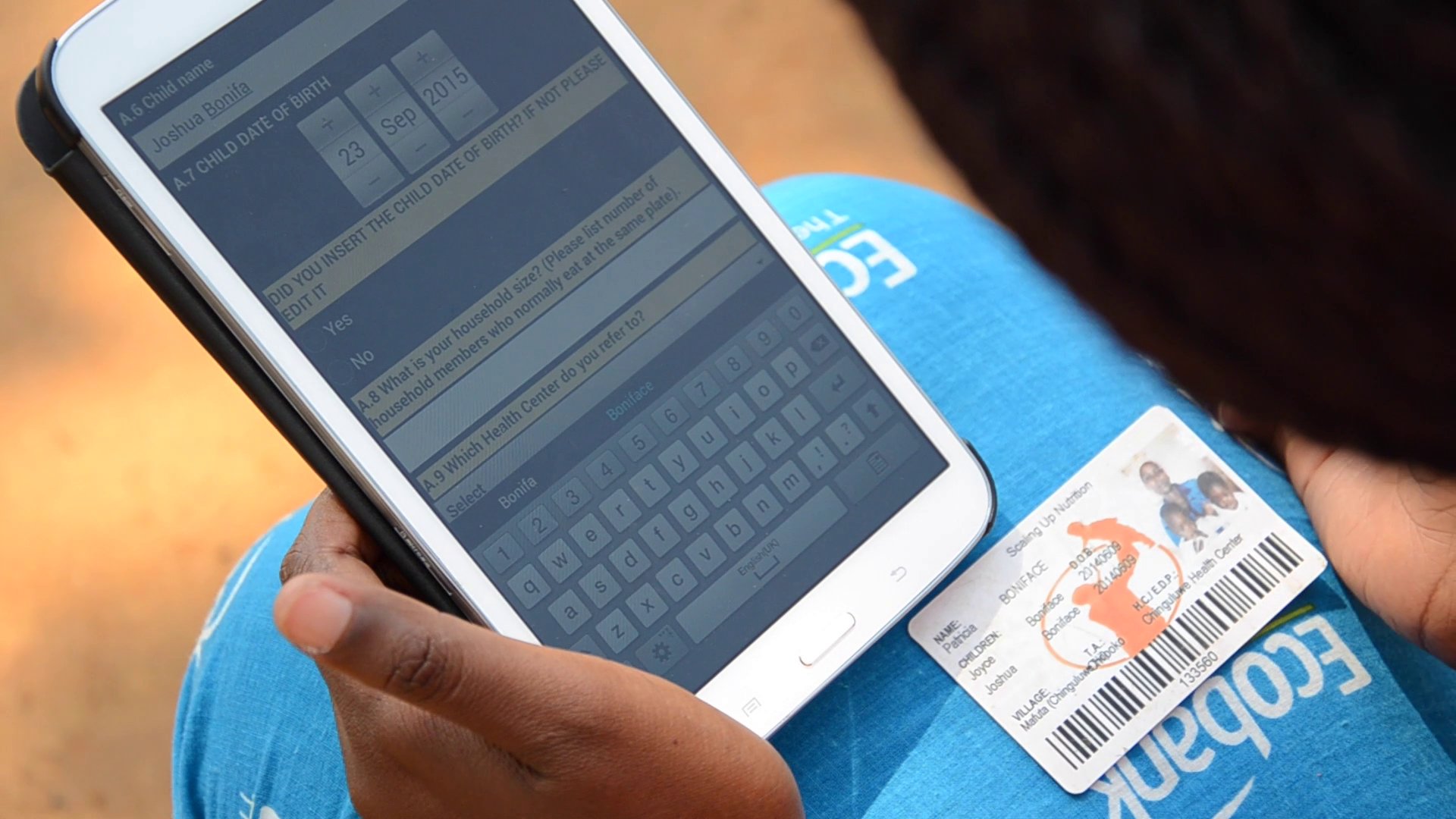

Photo Credit: WFP/Uganda

One such initiative of the World Food Programme (WFP) has silently been utilizing novel innovations to implement small and large-scale changes to deliver on its mandate to end hunger. In 2014 WFP kicked-off its first Innovation Challenge, an internal WFP challenge to source “great innovations within the organization” and “harness the power of innovative staff” to make small and large scale changes. Over 100 ideas were submitted to the challenge ranging from remote mobile surveys to determine food security to a biometrics project to ensure identity when distributing food assistance.

The success of the Innovation Challenge saw the introduction of the WFP Innovation Accelerator with the dedication to solving hunger and its root issues that have previously been a burden to development. Handed down directly by Ertharin Cousin, WFP Executive Director, the accelerator links the latest business model and technology trends with WFP’s mandate to end hunger.

Related articles: “UNITED NATIONS: GEARING UP FOR AGENDA 2030”

“ZERO HUNGER GENERATION — THE ROAD IS PAVED”

I had the opportunity to speak with the Head of the WFP Innovation Accelerator, Bernhard Kowatsch, about what type of innovations are garnering support and the real impact of using an innovation accelerator to solve social challenges. “The starting point for the accelerator,” he said “was the recognition of the need for better ideas and implementation.” “The Innovation Accelerator takes the best practices of a Y Combinator and … [brings] that to the humanitarian and development base.” Strapped like any startup, it takes roughly 3 months from proof-of-concept to move onto the next scale of stage. In 3-month intervals, there is a dedicated team fostering and supporting all the innovations proposed.

A second internal Innovation Challenge launched in 2015 has sourced innovations from over 150 countries. The most viable innovations are happening somewhere out there” and could have a positive effect if applied in a focused project directly by WFP. When asked for some specific examples drawn directly from the Innovation Challenge, Kowatsch grew excited. I could see this was work he was passionate about and happy to share their many recent successes. He expounded, “it is not possible to just develop innovations in a room [filled] with people.” He went on, explaining you need people on the ground, “harnessing the power … giving people the platform of great work that is happening.”

The Innovation Accelerator takes the best practices of a Y Combinator and … [brings] that to the humanitarian and development base.

In December 2015, four Innovation winners were chosen that exemplified the best and brightest ideas. Evaluating the current impact now and utilizing those results to prioritize accelerator support is, according to Kowatsch, the best way to ensure success.

One of the winning projects was submitted by a WFP team in Uganda. They utilized farming silos to improve food storage and limit post-harvest food losses. This project was particularly adequate in sub-Saharan Africa since “close to one third of local farming production is lost yearly due to inadequate post-harvest management and household storage.” Kowatsch explained how the innovation is not always the product in front of you, but the innovation can be “how you train people and scale it up. Working together with the private sector and NGO’s, scaling this from 6,000 to 60,000 small-holder farmers, we worked with innovative companies in small sections of the country relying on people with smartphones who are operating on their own. The silo triples household income, without anything else.”

Photo Credit: WFP/Malawi

To improve food assistance, real-time data usage and monitoring was proposed to identify those who are undernourished and the types of assistance they need. Ultimately, utilizing mobile calling and local surveys, WFP can determine where specific gaps in nutrition are on the ground level and how to optimize assistance.

Based on the success of the ideas brought forth internally in the Innovation Challenge, Kowatsch stated that in 2016 they are planning on opening an external innovation challenge to understand how we “communicate and connect with external networks, startups, and entrepreneurs who care about social causes, universities and think tanks.” This would be a huge step for WFP since currently all innovations sourced through the challenge are internally produced at WFP and utilized via WFP partnerships and startup collaborations.

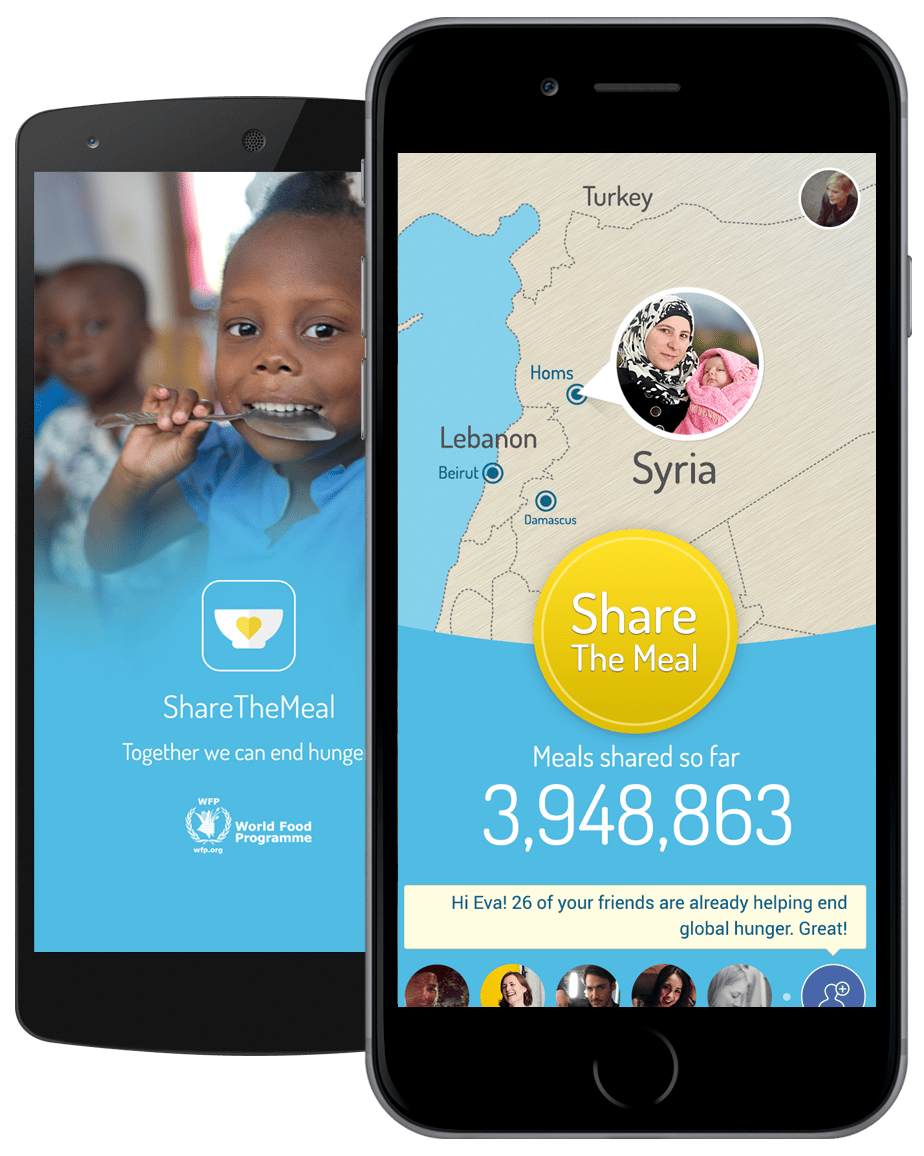

One of Kowatsch’s arguably “favorite” applications, although he shies away when I use the word, is the ShareTheMeal app. It began as a small pilot project he developed in collaboration with Sebastian Stricker, founder of the SharetheMeal app. In 2014, a prototype was funded by the Federal Republic of Germany, business angels, and a grant from WFP.

It only cost US$0.50 to feed a child for a day. We just need to make it easy for people to do good.

The objective is simple: It provides users with the opportunity to “share their meal” with those in need. In December of 2015, in its first year of operation, the application had already reached 20,000 refugee children living in camps in Jordan, providing them with school meals for a full year. Currently, the application is targeting pregnant and nursing mothers and their children who are living in Homs, Syria. The support is provided directly by the World Food Programme to ensure those in need are cared for.

This application is unique however in that it relies on users making small micro-donations in the form of global crowdfunding. I downloaded the app myself to see the social impact that is tied to fighting hunger. Immediately you are prompted to connect your Facebook account, and although I am typically wary of connecting social profiles to apps (Candy Crush, I am looking at you), it was great to see who else in my “social community” has already donated. I am also able to see that currently, 56% of the goal to reach pregnant and nursing mothers in Homs, Syria has been completed as well as the total impact to date with other projects ShareTheMeal has previously focused on.

What was special about this project, Kowatsch noted, was the intersection between technology and philanthropy. For example, what was particularly striking was that “it only cost US$0.50 to feed a child for a day. We just need to make it easy for people to do good,” he said, “focusing on a specific target, contributing to a bigger goal, every meal counts and adds up to something that is significant.” Looking at what can be done to enable global action and allowing the app users to have a say in where their funding is going empowers them to make changes that would have not been possible otherwise.

As we progress further with technological innovations in support of development, Kowatsch emphasized the importance of crowdfunding and micro-donation models as critical players.

Photo Credit:WFP/ShareTheMeal

The key success factor here is that it’s made easy. Smartphones allow you to have more benefits than relying on a donation website, considering the different steps required, from notifications to inviting your social community to contribute. By contrast, bringing whole communities together through the use of smartphones, larger donations and social connections can be made and fostered.

In the ShareTheMeal app example, there are over 470,000 active users and 4.7 million meals that have been provided so far. “Technology is one of the big primaries, the new normal for humanitarian response, the core of innovation,” says Kowatsch. Citing the second source of innovation as successful business modeling, he asks, “how can we disrupt the way we receive funding, how can we pre-empt crises before they happen?”

If we want to end hunger by 2030, we need to become better at actually implementing innovation.

Currently WFP maintains a flexible model of collaboration with innovators and other UN agencies and is looking into how it can achieve more productive collaboration either formalized or non-formalized. With a plethora of ideas being tossed around, one of the key principles to a successful Innovation Accelerator is the entrepreneur driving progress forward.

Encouraging all interested entrepreneurs or startups to get involved, Kowatsch states, “we are actively looking for some of these innovations to become self-sufficient or private-sector startups. We strongly believe that innovation is the key to ending hunger. Twenty years ago, 20 percent of the population was considered hungry, now 11 percent. We need to make progress if we want to make it to zero hunger by 2030.”

[1] Note: The Millennium Development Goals have been replaced in 2015 by the Sustainable Development Goals. Goal #2 represents ending hunger in all forms.

_ _