After twelve years of working as an advocate in the environmental and LGBT human rights movements, I started a career in the climate field in 2009. Nine years later I entered the energy field. I have learned a few things along the way.

1. People used to living on borders know things about intersections.

I was born and raised in Northern New York, on the Canadian border. It is a stronghold of individualism. In my youth, it was home to active military, veterans, and farmers, plus a handful of hippies living on the communes that popped up in the 1970s. I joke that the two political parties are Republican and Unabomber. Everyone hates the government for different reasons—sometimes excellent reasons (ask any Vietnam War veteran).

I knew by fourth grade that I did not fit in there. I came out as bisexual when I was in college, but I had access to queer culture before that, thanks to the hippie-children I met at Model UN. We went to Canadian gay bars, voraciously read Susie Bright’s books on feminist sex-positivity, and tried on different gender presentations. This was a healthy counter-narrative to grade school, where different was wrong.

Though I had my queer-positive posse, I have become clear-eyed about the conservatives who comprise the majority of my neighbours. They would support the current administration, with its xenophobic, white-supremacist narrative. They distrust the “liberal media” that talks about climate change (the climate has always changed!). I also have compassion for them. My parents, returned Peace Corps volunteers who came from the city, pushed me to broaden my horizons. If they hadn’t, I would have grown up in a rural bubble. There would not have been many opportunities for education or employment. Especially under the unmitigated influence of the institutions that produced the segregated community in which I grew up.

I left and got citified, but part of me will forever be rooted under that vast sky. My survival ties to that of the people who still eke out a living on that rugged borderland. It also ties to my queer community. And, as my world has enlarged, I see my survival also connects to that of all marginalized people.

I have not seen a statistical analysis. However, from my experience people living at the margins are often more resilient in crises. The social norm at the margin is mutual aid. In a rural community, you would never turn away a stranger whose car broke down on your road. People in the country discuss the weather not because we have nothing else to talk about. Where I grew up, we discussed the weather because it is always trying to kill you. Therefore, sharing that information could be a matter of survival.

Similarly, my queer community is a repository of survival information for all kinds of crises, from homelessness to mental breakdown. Queer Facebook groups were my main source of information on wildfire smoke mask availability during California’s 2018 fire season. The queer community has a long tradition of pooling money for medical treatments or rent for the most vulnerable. In this way, marginalized communities may have stronger informal support networks than mainstream society. At the same time, climate change threatens marginalized people disproportionately.

Climate vulnerability is greater for those facing barriers to resources. The further society marginalizes you from the center of power, the greater those barriers. These barriers can be compounded. For example, climate vulnerability uses poverty as a proxy, and poverty correlates with gender. According to the U.S. census, the poverty rate is higher among women, especially women over 65, while global numbers show a higher poverty rate among young women, divorced women, and single mothers. Climate change puts a particular burden on women through displacement, civil conflict, crop failure, cook fire fuel and water collection hardships, and health impacts. More women die in natural disasters. Poverty and gender is one intersection, but there are many others.

Socioeconomic factors like race, health, language, age, and citizenship status are other contributors to climate vulnerability. Additional factors may be gender nonconformity (including being a woman but not conforming to society’s expectations, or being transgender or nonbinary), lack of access to identification documents and insurance, instability of natal family relationships, lack of legal and societal recognition of non-natal family relationships, exposure to trauma (including housing insecurity and sexual violence), or institutionalization. Due to the correlation between many of these factors and being lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ), the LGBTQ population may have a higher climate vulnerability than straight cisgender people. In particular, young LGBTQ people are vulnerable: one 2012 study found that 40% of the clients of homeless youth service providers in the U.S. were LGBT.

One frightening example stays with me. 20-year-old Sharli’e Vicks survived Hurricane Katrina only to end up in jail because someone in authority took exception to a transwoman using the women’s shower at the shelter where she was sent. In a disaster, Sharli’e’s safety will always be contingent on passing as cis-female or finding a shelter with trans-competent management.

2. This picture needs a bigger frame.

I call climate change an “everything problem”—it is not just about biodiversity or clean air. It touches everything. Climate change also touches everyone—a fire or flood can displace anybody, not just the poor.

I try to remember to pull the camera back and see that I’m not alone. While this problem affects everyone, it also could serve to engage everyone—tap humanity’s collective genius. And, while I can’t fix climate change, any small action I can take is better than no action. I think about T.S. Eliot’s words in “East Coker”:

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

“There is only the trying” is my motto most days. I might be small, my actions might seem inconsequential, and I will not live to see the ultimate outcome. However, I still have a heartbeat and breath, so I can keep trying.

Also, it’s the only ethical thing to do if you have privilege. I am a healthy, educated, employed white woman in a wealthy country. The people on the front lines of climate change—the people living at sea level in the Irrawaddy Delta—don’t get a choice, they just have to cope. So, I can use my privilege, and keep trying.

3. Secrets are everywhere. (So is hope.)

I do not know if this is a secret: there are a lot of queer women working on climate. These include many of my role models. (I project “queer” here: I do not know their preferred self-descriptors, just that they aren’t straight-identified.) Perhaps queer women are drawn to wicked problems like climate change, being accustomed to tackling intersecting oppressions. Perhaps we bring special tools to the table. We might provide skepticism about dominant norms and an openness to alternative approaches (see J. Halberstam’s Queer Art of Failure). Additionally, we seek out the hidden. The history of queer women was buried, but we learned to dig for evidence, and to find hope in uncertainty.

While seeking out hidden possibilities, queer women have become accustomed to being vigilant about hidden threats. You never know who is a secret misogynist or homophobe. I semi-closeted myself at my job in the energy field: I don’t decorate my cubicle with rainbows. I know there are relatively conservative people in my workplace. Soon after I was hired, a total stranger, a white cis-man, randomly unloaded on me in the break room. He thought illegal immigrants drain the welfare coffers, ignoring my comment that they can’t get welfare without a social security number. (I would know, I worked in an immigration law office.) It turned out he is a senior member of staff. So, I remain semi-closeted and wonder if there will be consequences if I become more public.

4. Allies are not obvious.

I do not presume anyone is either friend or foe. If you are flagging “Conservative,” such as my colleague yelling about immigrants, I still expect we could find common ground. Just the same, if you are flagging “Gay,” I don’t presume you are politically pro-gay. It is a sexual, not political, orientation. I can’t afford to navigate by overt signals of ally-ship without looking for further evidence. Everyone gets the same scrutiny.

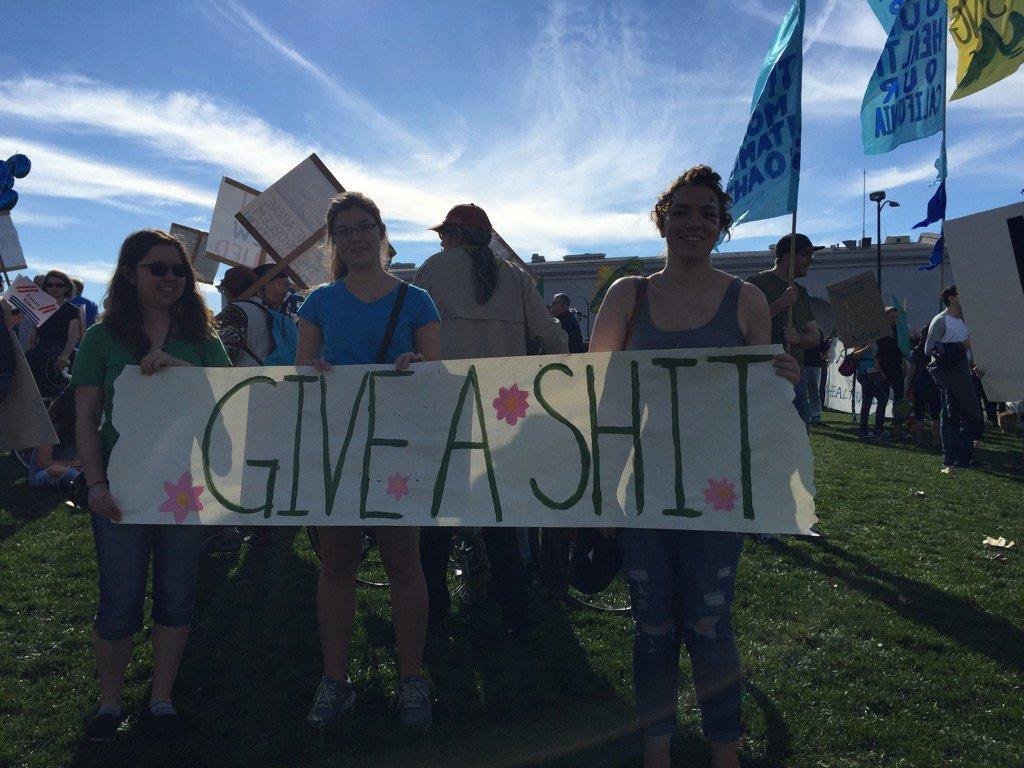

5. Attendance is everything.

I always aspire to be more than an armchair advocate for my ideals. Additionally, I try to connect in real-time to people who share my vision of a better world. Supporting a livable climate is a serious commitment that requires showing up. Whether it’s with a sign at a march or taking a work commitment to the next level.

I am inspired by the story of one Russian family’s commitment to science: for 58 years without interruption Dr. Lyubov Izmest’eva, her mother, and her grandfather measured the water of Siberia’s Lake Baikal every two weeks. They “quietly maintained one of the world’s most detailed and consistent limnological [inland aquatic ecosystem] monitoring programs.” One 2011 study used that data set to show that the lake’s “temperature patterns shift in concert with the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO).” Along with this amazing teleconnection to the Pacific Ocean, the data show rapid surface water warming correlated with global warming. This family had no promises that their work would amount to anything. Yet they created a data set that can support future climate action.

6. BOUNDARIES are also everything.

I attended a conference on transformational resilience a few years ago, and I’m still pondering what I learned in a session taught by Sarri Gilman, a marriage and family therapist. She wrote a book responding to the problem that front line social workers are often too overwhelmed to do their jobs properly. Climate impacts overwhelm those trying to address it in the same way. This includes people working in the post-disaster context, from public health workers to climate scientists. Being in the climate field can make you feel too overwhelmed to do your job properly. According to Ms. Gilman, the cure for overwhelm is boundaries, and you can set boundaries with a good yes/no compass.

I work every day at improving the strength of my yesses and no’s. I want to really mean it when I set a boundary. Being socialized as a woman, I tend toward the “go along to get along” position. To make things muddier, as a queer woman I feel that my personal choices always have a political dimension. I worry both about taking a stand and staying silent. Going to a march usually gives me a boost, helping me feel connected to my community. However, burnout is a real risk: I cannot attend every march.

I also worry about modelling good practices. It does not matter whether it is for the next generation or just my co-workers. I should model a good yes/no compass as part of good self-care. We will all stay in this fight longer that way.

Editor’s Pick – Related Articles:

“Centering the Queer Patient Experience”

“Connections That Matter: Climate Change and Gender Equality”

7. Art saves lives.

When I first came out, I played Ani Difranco’s first two albums on a cassette that I wore to ribbons. “Looking for the Holes” still gets stuck in my head:

Do your politics fit

between the headlines

are they written in newsprint

are they distant

mine are crossing an empty parking lot

they are a woman walking home

at night, alone

they are six strings that sing

and wood that hums against my hip bone

Those words have carried me across many empty parking lots at night. I have always found solace in art. It catches me when I fall. I once told a friend that I felt desperate, and he said, “You are too creative to be desperate.” Fashion professor Tim Gunn once said, “there is no excuse ever to lack inspiration.” On Project Runway he railed at depressed designers to walk outside, look around, go to a museum or a movie—inspiration can be found anywhere. This is advice I try to follow.

I also believe we need to inspire each other. In the 1990’s and early 2000’s I performed at and facilitated queer spoken word events. I see storytelling as an important survival activity for the queer community, and for any marginalized community. It is how we share our stories of overcoming trauma, or at least transforming it into art. Climate change gives us both adversity and the opportunity to share survival stories.

8. Listen to women of color.

I learn about ways to stay strong in the face of adversity and loss by listening to women of color. This includes transwomen of color. I recommend to those who attend climate or energy conferences to scan for women of color at the next gathering. Figure out who they are and when they are presenting. Show up, listen, and if you speak, ask a thoughtful question. Preferably, start with an expression of gratitude for their work.

When I recommend that people seek out women of color at a conference, to clarify, I am not saying go find them and ask them to teach you. I mean attend their presentations, ask thoughtful questions, and read their books. If they are teachers at your university, attend their classes and support them when they are up for tenure.

9. Persist.

A 2018 report shows that young people, especially young women, are growing less tolerant of LGBTQ people in the U.S. A 2016 study shows that a resume flagging a woman as having worked at an LGBT student organization got 30 percent fewer callbacks than a similar resume that mentioned working at another, non-LGBTQ, progressive student organization. Prejudice persists. So must you.

More experienced female colleagues in the energy sector told me the key to success: be willing to defend your assertions with evidence when challenged. One friend said her male engineer colleagues in the solar field were more pleasant to her than to each other. She found them more incensed than her when a man challenged her credibility or was condescending to her. She was used to it; they were not.

10. Safety might be where you least expect it.

I often ponder Margaret Atwood’s poem, “The Two Fires”. It references a 19th-century settler family surviving a summer forest fire and then a winter cabin fire.

each refuge fails

us; each danger

becomes a haven

I think about this poem especially when I ponder what climate change is asking us. Whether to contract our world, reduce, retreat, or whether it is asking us to transcend, explore, burst our customary boundaries and invent something new. The danger could lie in staying within our comfort zone, it could lie in going too fast outside this zone. For example, what false assumptions are we making about our public infrastructure? Is any height of seawall high enough?

~

I hope these bits of wisdom are helpful to you, dear reader. Particularly if you are a young queer woman considering a career in climate change, energy, or another STEM field. I recommend you keep a journal as you go. Someday you might be able to share insights with the next generation.

Learn more on Sara Moore’s Adaptation Blog, The Past is Not an Option, and follow her on Twitter: @stripeygirlcat

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com – In the Featured Photo: Rainbow falling upon a hilltop with a windmill in Montescudaio, Italy. Photo Credit: Chris Barbalis via Unsplash