(Part Two)

Part One of this article provided an explanation of who indigenous peoples are, why they are considered a special legal category, and what rights they have as outlined in international law. In this piece, I explore how colonization has affected indigenous groups and what prevents their communities from achieving sustainable development.

The Legacy of Colonization

When discussing the problems of development many indigenous communities face, I always make a point that the root of such disastrous conditions is, in part, in the colonial legacy affecting indigenous peoples even now. I often, however, get to hear that (1) I should get over it as colonialism is in the past; (2) it’s not the first time it happened that a weaker group was colonized and abused; or (3) governments have apologized (e.g., New Zealand, Canada, Taiwan), they have been pouring resources to those areas, what else do you want?

I personally want such individuals to understand that:

1. Colonialism may well be in the past, but its effects are not: indigenous peoples worldwide lost their land, resources, connection to ancestors in burial places, and control over their lives. This in turn broke down traditional structures, institutions, and families. Residential schools established to ‘civilize’ indigenous people destroyed indigenous education, cultures, languages, identities, and ties to communities.

Reconciliation efforts have been superficial and on the terms established by dominant groups – those who colonized and created top-down racist power structures in the first place. Apologies are window-dressing – Taiwan’s president apologized last year (2016) and promised the establishment of a historical and transitional justice commission. Qualitatively nothing has changed. Not in Taiwan, not anywhere else.

A continuing injustice is what indigenous people have been suffering from despite the fact that on paper colonization ended.

2. The fact that this happened in the past only means it shouldn’t happen again. For this we need to ensure that minority rights are protected, past legacies and their impacts are assessed and addressed.

3. In spite of the aid proffered, who owns the land and control the resources? Once a Chinese person in Taiwan told me everyone would like to be indigenous in Taiwan because of all the perks indigenous people get. Let’s take a look at the so-called perks and development projects and aid.

Land rights and resources

One of the key issues on the agenda of indigenous groups is the issue of land rights and control of resources their traditional habitats hold. Land is not solely an economic asset that allows indigenous groups access to natural resources, hunting, farming, or gathering.

Land has a spiritual and cultural significance, forms a space to maintain and protect traditional institutions and structures to help exercise autonomy and self-determination. Control over land also allows indigenous peoples to protect the environment.

International law (UNDRIP, ILO C107, and ILO C169) stipulates that indigenous groups have a right to territorial control of their homeland and to cultural practices that are connected to that territory. Governments and corporations, however, try to take control of indigenous land through various means. Indigenous land is wanted for a country’s “development” and “progress”.

Indigenous peoples in many countries face relocation of their communities for projects that are supposed to bring economic advancement. Cambodia is one such example. In order to build a dam for energy-poor and dependent Cambodia, the government and the Cambodian-Chinese consortium wanted to relocate an indigenous group from their traditional territory, providing families with a compensation.

Apart from the negative influence such relocation can have on the traditional way of life, connection to ancestors, and indigenous collective identity, the new land they received brought damage to their community as it was not good for farming, too far from the forest, and eventually affecting fish migration and water quality. Fierce opposition to building of the dam has caused confrontations between indigenous people on one side and officials and the company on the other. As in many such similar cases around the world, indigenous people were threatened with murder and destruction of their property, and in some cases treated as political opposition which brings its own adverse consequences.

Despite the protests and the domestic and international laws that recognize indigenous rights, the dam was still built.

Storage of nuclear waste on the Orchid Island in Taiwan is another example. The Island is a home to the indigenous group Dao. Since the 1970s, the government has been storing nuclear waste on the island without ever informing or consulting the Dao. The nuclear waste dumpsite was mis-represented to them as a fish-canning factory to help local people receive additional income and improve infrastructure and electricity.

IN THE PHOTO: DAO INDIGENOUS PEOPLE PROTEST AGAINST THE STORAGE OF NUCLEAR WASTE ON THEIR LAND – THE ORCHID ISLAND, TAIWAN. PHOTO CREDIT: CHANG TSUN-WEI.

The protests against the dumpsite started in 1988 when the Dao discovered what was stored on their land. Although the government has promised to remove the waste and provide a compensation, especially for the increase of the liver, stomach, and other types of cancer rate and birth defects among local people, the nuclear waste is still stored in the Island while consultations were conducted with the Paiwan indigenous people in yet another poor area of Taiwan about relocating it to their land for a compensation.

There are other examples of such criminal neglect of indigenous rights to land and informed consent, at the expense of their well being and the environment. The most powerful recent case includes that of the Standing Rock Sioux pipeline battle (USA) that saw a Native American community standing against an oil company and its backers who used threats and violence against them .

The First Nations in Canada are experiencing similar threats from oil extraction companies that are supported by the government. Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain project is one case in point. Not that far away are Russia’s indigenous groups in the North of the country that have been countering the expansion of oil and gas extraction to their lands for years, and the Sami people of Finland that are being affected by mineral extraction and the development of renewable energy projects.

And it’s not only about the abuse of indigenous rights to their ancestors’ land and resources. This is also about the environment in the territories they inhabit. In January 2017, an oil pipeline spilled 200,000 liters on aboriginal land in Saskatchewan, Canada. It’s not the first incident in Canada, and certainly not the first in the world. Oil spills pollute the environment: rivers, lakes, and the earth – on indigenous lands used by indigenous groups.

Another major issue with land rights and protection is the establishment of natural reserves and so-called conservation projects. Indigenous peoples are forcefully relocated allegedly for INGOs and governments to protect wildlife and the environment.

Indigenous rights abuses complaints against the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the largest conservation organization, are the most notable example. In Cameroon, anti-poaching “eco-guards” destroyed property of the hunter-gatherer Baka people, used violence against them, and denied access of the Baka to their ancestral lands. WWF, that helped the government establish these protected areas, never received a proper, informed consent of the Baka people as required by international law.

IN THE VIDEO: BAKA INDIGENOUS PEOPLE PLEAD FOR AN END TO ABUSE IN THE NAME OF CONSERVATION. VIDEO CREDIT: SURVIVAL INTERNATIONAL.

Not that far away, in India, an indigenous group was evicted from the Kanha tiger reserve to allegedly protect tigers. Despite the evidence that people can live peacefully with tigers and that indigenous people have been protectors of wildlife and wilderness for centuries. Similar cases can be found in Nepal, Kenya, and many other places.

Many indigenous rights activists have been murdered for opposing projects that are to bring “development” but that essentially mean deforestation, relocation of indigenous peoples from their ancestral areas, or other equally damaging projects that can be destructive to the environment and lives of indigenous communities.

In 2016, 200 people defending the environment and land rights of indigenous communities were killed. Among them are land rights activist Bill Kayong (Malaysia); Isidro Baldenegro López (Mexico) who fought against illegal logging, and Berta Cáceres (Honduras) for her activism against an internationally financed hydroelectric dam. 2017 saw the death of Alicia Lopez Guisao, a leader of Colombia’s Asokinchas community, who organized the Agrarian Summit Project to distribute land and food for 12 Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities in the country.

IN THE VIDEO: INDIGENOUS ACTIVIST BERTA CACERES WHO WAS MURDERED IN HONDURAS FOR FIGHTING FOR INDIGENOUS RIGHTS AND AGAINST ENVIRONMENTAL DESTRUCTION. VIDEO CREDIT: AJ+

Environment

The issue of land ownership and control is clearly tied to the environment. Indigenous peoples are believed to be the best protectors of the Earth due to their traditionally sustainable lifestyles and treatment of the land as a spiritual and cultural dimension of their lives.

Yet, they are seen by some governments and INGOs as an obstacle to development and conservation. And when a disaster happens due to this “development” (oil spill, landslides, etc.), it is indigenous communities that are affected most.

Indigenous groups are also the ones most severely influenced by climate change. Coastal communities in Alaska, for example, suffer and/or are predicted to suffer from the rising sea levels and coastal erosion. Forest fragmentation and droughts affect the livelihoods of indigenous peoples in the Amazon. The Kalahari Desert in southern Africa has experienced rising temperatures and increase wind speeds which led to the loss of vegetation and, thus, has had a negative impact on the lives of the San indigenous people who now heavily depend on the government. Glacial melts in the Himalayas endanger long-term water supply for local indigenous people. Changing ice and weather conditions in the Arctic region put health and physical safety of indigenous people living and traveling there at serious risk.

It is especially devastating because indigenous peoples’ negative environmental footprint is virtually nonexistent or very minimal compared to non-indigenous communities. Also, it is indigenous peoples across the world that have been at the forefront of protecting the environment through various means.

IN THE PHOTO: THE 2017 CLIMATE CHANGE MARCH IN WASHINGTON, D.C., INCLUDED A NUMBER OF PROMINENT NATIVE AMERICANS, SUCH AS CHIEF ARVOL LOOKING HORSE OF THE CHEYENNE RIVER SIOUX TRIBE, PICTURED AT CENTER. PHOTO CREDIT: INDIANZ.COM.

Indigenous peoples lead and are part of various projects that address the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation in their respective areas (e.g., adapting infrastructure, monitoring ocean acidification levels, establishing biomass and geothermal energy projects). They also share their traditional knowledge with scientists who acknowledge indigenous authority in management of the environment, wildlife, and natural resources.

Some examples of collaborative projects using indigenous knowledge include: development of marine turtle monitoring in Australia, wildlife management in Amazonia, and the improvement of knowledge of environmental changes in the Bering sea.

At a global level, indigenous peoples work with the United League of Indigenous Nations (ULIN) that has a special climate program and the International Indigenous Peoples Forum on Climate Change (IIPFCC). The 2015 Paris Agreement was an important step taken by the international community and indigenous peoples especially to start working as a unifying force to build environmentally sustainable societies. While the US administration under Trump rejected the Agreement – making the US with Syria and Nicaragua the only three countries that haven’t signed – Native American communities pledged to keep their commitment to support it and abide by its principles on their lands.

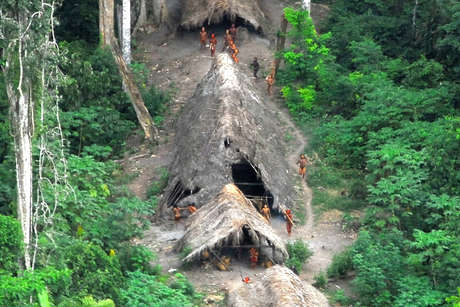

Uncontacted tribes

Closely related to land rights and protection of the environment are the rights, survival, and wellbeing of uncontacted tribes. Such groups lead a sustainable lifestyle in absolute harmony with nature.

While it’s impossible to say exactly how many of such tribes exist, Survival International, the organization that protects tribal peoples’ rights, estimates that there are over 100 groups around the world who have chosen to have no or a limited contact. It’s not to say that they are not aware of the world outside of their small communities – at some points they have had different encounters with outsiders. But out of fear of being murdered or enslaved – which has happened in the past and has been transmitted as oral history from generation to generation – they prefer not to engage.

IN THE PHOTO: AN UNCONTACTED TRIBE IN BRAZIL. PHOTO CREDIT: SURVIVAL INTERNATIONAL.

Their right to self-determination, violence inflicted on them and their land, and the threat of contracting diseases that can kill them are the reasons indigenous rights activists call for the tribes to be left alone. However, they often live in areas that are considered empty hence in need of development; that contain valuable resources wanted by governments and big corporations; or that are viewed as safe spaces to escape or control by criminals. Illegal logging on the border of Brazil and Peru and drug trafficking and resource extraction in Peru, for example, force local tribes to flee from their traditional habitat and seek help in the mainstream world where governments, very often, prefer to ignore their existence or assimilate them into the dominant society.

Health

Regardless of which country we are talking about, indigenous peoples’ health indicators are always lower than those of other groups. While reasons may differ from place to place, the general factors that predispose them to diseases and injuries are socioeconomic disadvantage (poor housing, unemployment, inadequate incomes, etc.), alienation from their ancestral land and culture, and environmental degradation.

Poor socioeconomic status leads to lower life expectancy, high child and maternal mortality rates, malnutrition, and increased levels of chronic diseases, for example. Alienation from traditional habitat and culture results in depression, substance abuse, and suicides. Environmental degradation can exacerbate all the above.

Access to healthcare, especially quality healthcare, is frequently limited for indigenous people. If such services exist at all, they are often culturally inappropriate, discriminatory, and not provided in indigenous languages. As the United Nations OHCHR study on “the right to health and indigenous peoples, with a focus on children and youth” stated back in 2016:

States often turn a blind eye to racism in health care settings, even in the presence of pervasive, persisting evidence that indigenous peoples are treated discriminatorily.

Indigenous culture and traditional practices that have a potential to help develop sensitive and relevant responses and the environment that would prevent diseases, are often overlooked.

Related article: FROM WHERE I STAND: MARIA JUDITE DA SILVA BALLERIO by UN Women

Education

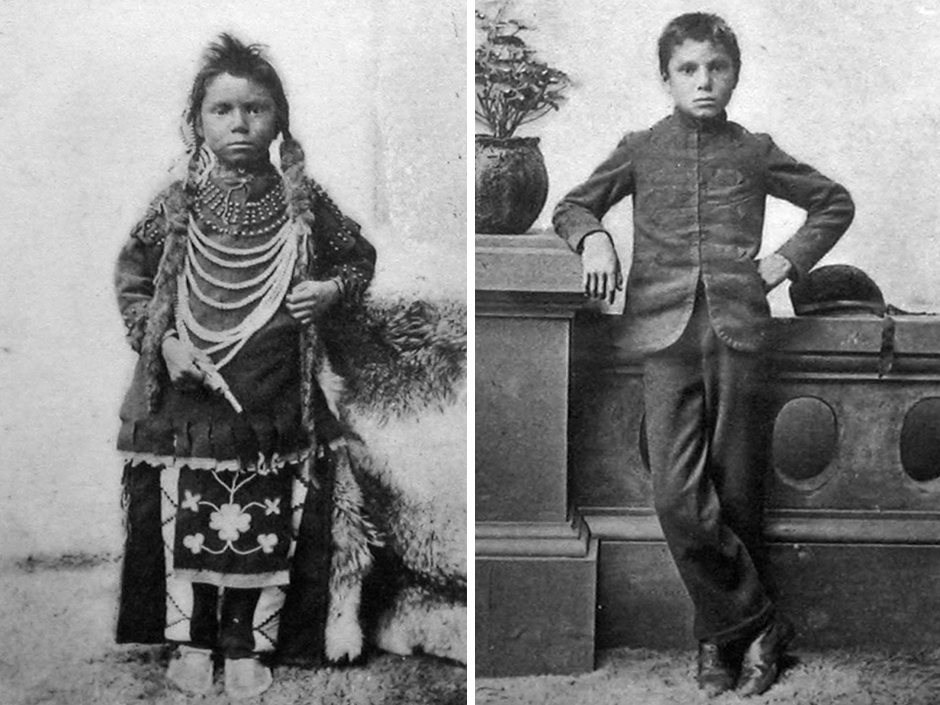

Since colonial times, indigenous people have been forced to attend mainstream educational institutions that promote dominant languages, values, knowledge, and beliefs at the expense of those indigenous peoples hold themselves. Because of such assimilationist educational strategies, many communities have lost their traditional knowledge and value systems and languages. Those who managed to preserve them to different extents, find themselves in a harsh reality where education systems and the society at large are not interested in supporting them in this endeavor.

IN THE PHOTO: AN EXAMPLE OF AN ASSAULT ON INDIGENOUS IDENTITY AND CULTURE IN A RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL IN CANADA. PHOTO CREDIT: LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA, 1897.

Mainstream schools are culturally-insensitive and contextually-irrelevant for indigenous youth, so they find little value and interest in them. Schools that serve indigenous communities specifically, lack well-trained teachers, often have inadequate educational resources, and still act to assimilate through their culturally inappropriate curricula. In both cases, such schools don’t represent the indigenous students, don’t reflect their realities and don’t consider their lifestyles.

As a result, indigenous people have lower levels of education, poorer educational achievement, and higher dropout rates as compared to other, non-indigenous groups. In general, their experiences in schools cause trauma due to the loss of a part of their identity, emotionally unsafe environment, and isolation from both mainstream and home communities. This feeds into health deterioration, substance abuse, depression, and may lead to suicides.

Poverty and underdevelopment

Lack of formal education and credentials valued by mainstream societies leads to high levels of unemployment among indigenous people or employment as manual labor in urban areas. Staying in indigenous communities in rural and remote areas may not always be an option – their rights to land, resources, traditional hunting and gathering activities, have long been tampered. Agriculture is an attractive option only for few, and that still is under threat in many cases. Rural areas in general have not much to offer hence migration to urban spaces which are often hostile to indigenous people.

Such developments have led to unsustainability and underdevelopment of traditional communities and rampant poverty in urban areas. A World Bank study found that indigenous peoples are not only poorer than all other groups, but also that their poverty is more severe than everyone else’s and this gap is not getting smaller with time, despite efforts.

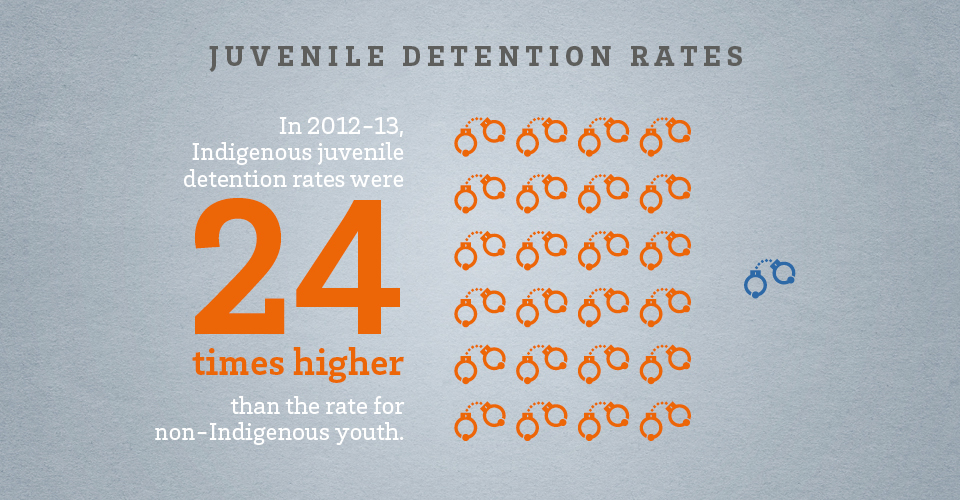

Their poverty is also not only about low income or lack thereof. It’s about general trends of indigenous peoples being less likely to live in adequate housing, being more likely to have limited or no access to safe water and sanitation, and being more likely to be malnourished. As with the other trends (e.g., land theft, lack of proper education), such processes lead to high levels of substance abuse, high rates of incarceration, prostitution, and suicide.

IN THE PHOTO: JUVENILE DETENTION RATES OF INDIGENOUS YOUTH IN AUSTRALIA. PHOTO CREDIT: AUSTRALIANS TOGETHER.

Racism and discrimination

Rampant racism, stigma, and institutionalized discrimination persist for many reasons, of course. Colonial legacy and its division of superior/inferior groups plays a big role in that, reducing the power and influence of indigenous people to zero. Lack of proper credentials and education is harmful not only for economic and social development of indigenous communities, but for the treatment indigenous people receive as they are seen ‘less than’.

Another important reason is misrepresentation of indigenous peoples in textbooks and media. This lack of real knowledge about indigenous cultures and histories, what dominant groups have done to indigenous communities and heritage and how they have driven indigenous people to the current level of destitution, leads to further stereotyping, bias, and discrimination.

Tourism

Creating ‘ethnic minority’ or ‘indigenous’ cultural parks to attract tourists has been one of the major ways to help advance indigenous peoples out of poverty.

On the surface it sounds like a great plan – indigenous people ‘preserve’ their cultures and traditions and earn money by doing so: tourists find it adventurous, inspiring, and authentic to watch indigenous dances, listen to indigenous songs, and buy ‘authentic’ indigenous arts and crafts.

First, there’s nothing ‘authentic’ for indigenous peoples in this. They are forced into a box of oppressive authenticity: someone else – those who pay for the show – decide what indigenous is expected to be. And they are expected to be ‘the other’ in visible ways: in what they wear (traditional clothing becomes a ‘costume’), what they perform (sacred ceremonies become ‘shows’), and where and how they live ( seen as primitive, simple, and close to nature).

But that is not all. Their physical environment suffers too. In Thailand and Malaysia, communities were displaced to build hotels on the coasts. In Canada, Hawaii, and Indonesia, indigenous burial grounds were threatened by the expansion of tourist resorts. In the Amazon tourists disrupt sacred religious ceremonies. Such examples can be multiplied: indigenous archaeological sites are plundered, land desecrated, and people are exploited as low-paid or forced labor or used in the growing sex tourism industry.

Cultural Appropriation

Another issue is appropriation of indigenous cultures – which non-indigenous people disrespect, misuse, and misrepresent. Cultural appropriation happens when a fashion, fine art or entertainment industry uses traditionally indigenous sacred items and patterns (headdresses, clothing patterns, etc.) to make a profit. High-end fashion houses have been accused of (ab)using indigenous beading, feathering, and other sewing techniques without any consent from indigenous groups.

Cultural appropriation is not only a big business for Chinese factories or western fashion houses, however. It is an identity theft by non-indigenous individuals who imagine themselves as ‘tribal’, ‘awake’, and ‘spiritual’ by wearing Native American headdresses, putting on ‘tribal’ makeup, donning ‘indigenous’ jewelry and clothing, or living in a teepee during some sort of ‘spiritual’ festival.

IN THE PHOTO: A FESTIVAL-GOER WEARS A HEADDRESS . NOTE THAT INDIGENOUS HEADDRESSES BELONG TO SPIRITUAL DOMAINS OF FIRST NATIONS AND ARE NOT TO BE WORN CASUALLY, ESPECIALLY BY NON-INDIGENOUS PEOPLE. PHOTO CREDIT: OLLIE MILLINGTON/WIRE IMAGE

As Pegi Eyers describes it, it’s an act of racism to use indigenous cultural markers. Not long ago indigenous people were killed for using them and it interferes with indigenous attempts at “resurgence and sovereignty.” Pegi Eyers explains that:

Cultural appropriation dominates how oppressed groups present themselves to the world, and undermines their efforts to preserve their own traditions.

This year, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), an agency under the UN, was asked to develop “effective criminal and civil enforcement procedures” to stop cultural appropriation of indigenous heritage. It seems that open letters to non-indigenous people and other attempts to stop this cultural, spiritual, and identity theft aren’t helpful, and legal measures need to be taken to protect indigenous communities from such abuse.

On the downside, it is clear that indigenous people still have a long way to go to achieve full recognition. But, on the upside, the good news is that general awareness of their plight has been raised and that the road to achieve justice for them has been traced. It now needs to be taken.