The early 2000s saw coltan help further technological development – but at what cost to the DRC?

To understand the weight coltan has on the people of DRC and its wildlife, we need to talk about what coltan is. Also known as columbite-tantalite, coltan is a metallic ore that is mined in the eastern part of the DRC, it is one of the most important minerals for today’s technology.

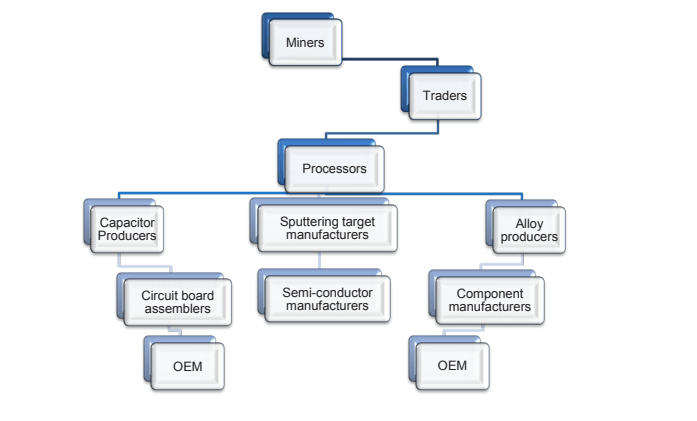

Niobium and tantalum are extracted from coltan, with tantalum specifically playing a key role in the electronics industry. Its usage specifically contributing to capacitors, surface acoustic wave filters for sensors and touch screen technologies, hard disk drivers and led lights – according to the Polinares Case Study.

You will know touch screen technologies quite well, in fact, you’re probably using one to read this right now. The majority of the world’s population use smartphones, Statista states that China, India and the United States easily surpass the 100 million users of smartphones mark alone.

Tantalite was first discovered in the Congo in 1910 through artisanal mining. ABC News reports that the mining itself is done in a primitive manner, with men working together to dig large craters in stream-beds and scraping dirt away from the surface in order to find the coltan. A worker can produce one kilogram of coltan on a good day.

However, an issue with mining coltan is that the process is complex and long, making it difficult to pin-point exactly where it is sourced. Due to this process, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) may experience confusion between legitimate and rebel mining practices.

Despite this, it is estimated that coltan mining and trade employed hundreds of thousands of people in the DRC. Additionally, artisanal mining supports up to 16% of DRC’s population – according to the Polinares Case Study.

But this large number of employment, whilst appearing to be successful and booming, doesn’t come without setbacks. Statista states DRC is the fourth largest population in Africa as of 2020, with 89,561 thousand people. The country’s quality of life is low and compared to other countries in Sub-Sahara Africa, its economy is very poor.

Bad economy goes in hand-in-hand with weak infrastructure, meaning these miners face difficult working conditions due to travelling to-and-from mines via poor road systems at large distances. The BBC states that the DRC has barely any roads or railways, with a health and education system mostly obsolete.

Regardless, the mining industry historically in the Congo made up 25% of its GDP, noted by the Polinares Case Study. Whilst the DRC’s mining efforts contributed and profited from large projects, poor economic management and political struggles contributed to the drop of the sector’s share of the GDP to 6% in 2000.

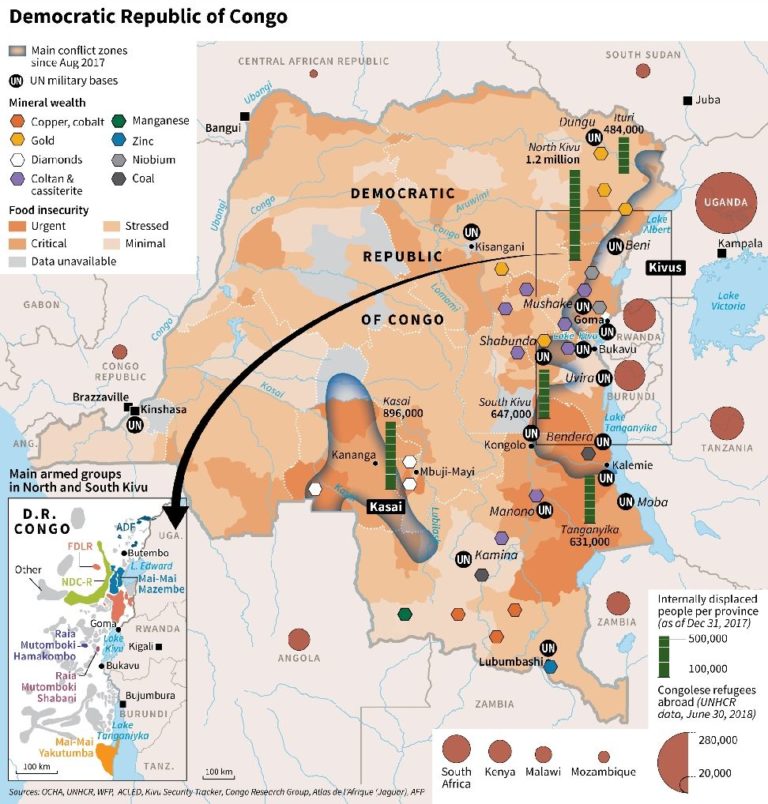

This was not helped by conflict in neighbouring states, such as Rwanda, contributing to the higher chance of violence in the DRC, alongside the common knowledge of the DRC being mineral rich.

It is well-known that non-renewable resources, like minerals make countries vulnerable to conflict. The mining of coltan contributed to this in the DRC, due to it being extracted in the 1990’s before the First Congo War as a by-product of tin – making it limited.

Coltan mining boomed in 2000, prices rose rapidly, attracting many workers as it was seen as an unmatched way of making money. It did not only attract adults, many children were drawn to the ‘gold-rush’ of coltan mining.

According to the Polinares Case Study, a teacher noted that more than 30% of children in 2000 dropped out of school to mine coltan. What attracted these people to the mines, ABC News notes, is that coltan mining pays very well. The average worker in the DRC makes $10 a month, whereas a miner can make between $10 to $50 per week.

More than 30% of children in 2000 dropped out of school to mine coltan

The boom didn’t last long, prices of coltan crashed in 2001, with artisanal miners ditching coltan mining and production. This resulted in the mining, production and trading being taken over by armed groups as a source of revenue.

Coltan’s link to conflict goes back further than this, though, during the Second Congo War between 1998 and 1999, the Rwandan army ransacked over one thousand tonnes of coltan from the eastern part of DRC and brought them to Kigali.

They also generated revenue by creating illegal taxes on coltan and gate-keeping mines. The RCD rebel government used coltan for revenue in 2000, making $1 million monthly exporting coltan, compared to $200,000 monthly from exporting diamonds.

Competition between these groups over the control of coltan often leads to violence, leaving devastation in their wake on the sites and the workers caught in the middle.

RELATED ARTICLES: Making the Crisis Connection: Global Security, the Environment and Climate | Transform Together: Become Prouder of Your Smartphone and Help to Achieve the SDGs | Shrinking the Environmental Footprint of Mining

As of 2020 children in the DRC still continue to work in the mines, where they earn just $21 weekly and work constantly with no day off. Children are also at risk of sexual advances being made at them by their employers, alongside working inside narrow manmade tunnels that can potentially cause permanent lung damage.

Amnesty International have raised concerns over these conditions back in 2016, accusing Apple, Samsung and Sony of failing to do basic checks over where their smartphone metals are sourced from.

A lawsuit was filed on behalf of fourteen parents and children from the DRC by International Rights Advocates, naming Apple, Google, Dell, Microsoft and Tesla as defendants. The companies were accused of aiding in the death and serious injury of children who worked in mines in their supply chain.

Coltan mining not only causes human devastation, but it also creates masses of environmental damage. Forest clearance and water use being large factors in environmental harm caused by coltan mining.

Michael Nest, anti-corruption expert and author of Coltan (2011), also pointed out that when a coltan deposit is found, “miners rush in to exploit the site, regardless of whether it is on agricultural land or in a national park, and the mining destroys the potential for the land to be used for grazing or cropping, or as a biological reserve for fauna and flora.”

Coltan mining also poses a great threat to gorillas. The Gorilla Fund website reports that Grauer’s gorillas – which are found only in the DRC – numbers have fallen by nearly 80 percent over two decades due to the effects of mining. There is fear that they will go extinct if the situation doesn’t change.

There are organisations tackling the effects of coltan mining in the DRC, one being Humane Society International. They have partnered up with Born Free, to provide vital funding and support to the Grauer’s Gorilla Conservation initiative. According to the Born Free website, the initiative researches, monitors and protects the endangered species in the DRC.

We have managed to get a statement from Evan Quartermain of Humane Society International/Australia, who notes the ongoing struggle of gorilla conservation and what can be done to make a change.

“Fortunately significant conservation efforts appear to have recently arrested this decline [of endangered Grauer’s Gorillas], but with numbers still critically low there’s absolutely no room for complacency. Simple acts like recycling old mobile phones and chargers can help reduce the demand for coltan mining.”

Another organisation tackling the conflict-material crisis in the DRC, is The Responsible Minerals Initiative, founded in 2008 by members of the Responsible Business Alliance and the Global e-Sustainability Initiative.

Their Responsible Minerals Assurance Process gives companies and suppliers a third-party audit, determining which tantalum smelters and refiners have systems in place that responsibly source minerals without the exploitation of children and the environment. Tantalum smelters have been taking part in the program since 2010.

Apple’s Conflict Material Report of 2019 shows that Apple has been using existing programs to source minerals such as tantalum responsibly. Samsung also operates a mineral management system: OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas and share their smelter list openly with stakeholders and customers.

Hopefully more businesses continue to follow suit with these initiatives, to clear the murky water that is the lengthy chain of the mining and trading practice of coltan, and begin to reverse the impact it has had on the DRC.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. In the cover photo: A Coltan Mine Photo Credit: ©MONUSCO/Sylvain Liechti