Non-communicable diseases are the major global health issue that most people have never heard of. Yet it kills nearly 40 million people every year, more than traffic accidents (1.3 million) or scary communicable disease outbreaks like Zika and Ebola that do make it in the news, but rarely exceed 10,000 deaths. For example, the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa killed 11,310 (latest Centers for Disease Control data).

NCDs include four major diseases that you can’t catch from someone else:

- cardio-vascular diseases (stroke and heart attacks, 48% of NCD deaths),

- cancer (21%),

- chronic respiratory diseases (12%),

- diabetes (3.5%).

This is not to belittle the threat or devastation caused by communicable diseases. Currently, the massive cholera outbreak in Yemen that has infected some 800,000 people in the past year and a plague outbreak in Madagascar that has killed nearly 100 people in two months are making the news. Rightly so, these are people in urgent need of help.

But NCDs should not be underestimated: They cause 70% of deaths globally, and nearly 50% of global disability. High-income countries are more affected than low-income countries (88% vs. 37%, 2015 data). As a result, there is a misperception that NCDs are a high-income country problem, but that’s not the case.

It’s a global problem.

In terms of absolute numbers, NCD deaths are far more numerous in low-income countries than in the developed world that benefits from functioning public health systems and generally accessible disease prevention measures and treatment. 4 out of 5 of NCD deaths occur in developing countries, and if nothing is done to reduce them, WHO estimates that this will add up to stunning total of US$7 trillion in cumulative economic losses over the next 15 years.

NCDs have grown alarmingly in developing countries since the 1970s, as risk factors, unknown before countries opened their doors to global trade, suddenly began spiking – notably rising consumption of tobacco and sugary drinks. Even the poorest can afford the occasional luxury of a cigarette or a Coke, and with growing incomes, consumption of American products symbolizing the middle-class way-of-life has skyrocketed.

In the Photo: Beedi smoke at sunset (India) Photo Credit: Shreyans-Bhansali (Flickr)

But NCDs have grown alarmingly everywhere, including in the developed world. Some NCDs are getting worse, obesity in particular. The epidemic that started in the United States is now on the rise everywhere. The number of obese adults increased from 100 million in 1975 to 671 million in 2016, with more women obese (390 million) than men (281 million). Another 1.3 billion adults were overweight, but fell below the threshold for obesity. A new study by Imperial College London and WHO published in The Lancet ahead of World Obesity Day (11 October 2017) warned that children were at special risk:

The world will have more obese than underweight children and adolescents by 2022, a result of a tenfold increase in childhood and adolescent obesity in four decades.

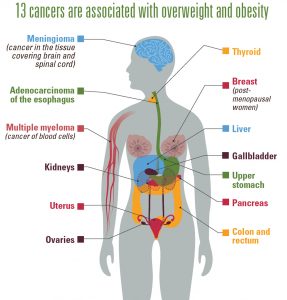

Equally worrisome: Recent data from the US Centers for Disease Control (CDCs) showed that overweight and obesity are associated with increased risk of 13 types of cancer, accounting for about 40% of all cancers diagnosed in the US. In 2014, 630,000 Americans were affected. While the rate of non-obesity cancers declined from 2005 to 2014, obesity-related cancers increased by 7% (excluding colorectal cancer, a case apart as it is amenable to resolutive treatment if taken in time). This is why regular colon cancer screening is important—just like any other types of cancer, early detection of colon cancer makes a huge difference in the effectiveness of the treatment.

Photo Credit: CDC diagram

The Strategy to Beat the NCDs: Four by Four

The continuing rise in NCDs threatens achievement of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Yet health scientists and professionals feel strongly that the NCDs are not a lost cause, they can be beaten.

Along with the four diseases identified as causing the bulk of the NCDs, four main risk factors caused by people’s lifestyles were also identified:

- tobacco use,

- unhealthy diets,

- physical inactivity,

- alcohol use.

Since these are all major risk factors that can be modified and controlled by people at a relatively low cost, it became apparent that they were the key to beating the NCDs. Soon, the strategy was given a catchy name: Four by Four.

An earlier version of this strategy was enshrined in a major World Health Organization decision: Resolution WHA. 53.14, adopted by all the 194 state members of the World Health Assembly (WHA), and published in March 2000.

Widely considered a historic watershed, it capped a long process of discussions at WHO in the 1990s and launched for the first time a global strategy on noncommunicable disease prevention and control. The Director General’s Report presenting the Resolution admirably encapsulated the achievement (my highlights added):

Four of the most prominent non-communicable diseases – cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes – are linked by common preventable risk factors related to lifestyle. These factors are tobacco use, unhealthy diet and physical inactivity. Action to prevent these diseases should therefore focus on controlling the risk factors in an integrated manner.

Since that was written, as we know, a fourth factor was added: alcohol use.

Yet, in spite of increased global awareness of the risk factors and of the need to amend lifestyles, the expansion of NCDs has been relentless.

As Richard N. Haass, an American diplomat and President of the Council on Foreign Relations recently noted (in the 2017 Report Card on International Cooperation):

“The World Health Organization and major health aid donors should shift more of their attention and resources to combating the surging threat of noncommunicable diseases (including lifestyle related conditions like obesity, lung cancer, and heart disease) in the developing world.”

WHO’s Latest Effort in Fighting the NCDs: The Montevideo Roadmap

WHO is certainly following Haass’ advice as it seeks to play a major role in bringing the world’s attention to this issue and kickstart national policies to address the NCDs.

Most recently, it convened a Global Conference on NCDs in Montevideo, Uruguay, with the aim of accelerating efforts by member states to achieve the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal target 3.4 that calls for reducing by one-third the number of “premature deaths” from NCDs by 2030. The term “premature” refers to the over 15 million people (38% of NCD deaths and 27% of all global deaths) who have died between the ages of 30 and 70, most of which could have been prevented or delayed.

In the Photo: Banner of WHO Conference on NCDs, held in Montevideo, Uruguay 18-20 October 2017. It resulted in the adoption of the Montevideo Roadmap. Photo Credit: WHO

To understand the nature of the challenge, consider that 85% of premature deaths from NCDs occur in developing countries, including 41% in lower-middle-income countries where the probability of dying from an NCD between the ages of 30 and 70 is up to four times higher than in developed countries.

The point of the Uruguay Conference was to galvanize political action and draw a roadmap, influencing public policies in various sectors, health, trade, and education, among others.

Unfortunately, the Conference’s outcome document was largely ignored by the mainstream media, as the world got distracted by news that Zimbabwe’s controversial president Robert Mugabe not only had attended the Conference but had been designated as WHO Goodwill Ambassador for NCDs in Africa. Mr. Mugabe, an irascible 93 year-old who avoids the public health facilities in his own country (decimated by his own policies) and regularly relies on treatment in Western luxury clinics, is a notorious autocrat and serial offender of human rights.

Two days later, on October 22, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO’s recently elected Director General, retracted the nomination, but the damage was done. Unsurprisingly, the media preferred to talk about Mugabe and the “scandal” of the nomination instead of speaking of the fight against NCDs and considering what WHO proposed to do about it.

In the Photo: WHO Director General Tedros and President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (collage) Photo Credit: Wikipedia commons

A UK spokesman told the UK Guardian the WHO decision was at odds with US and EU sanctions against Mugabe and the US state department said the appointment “clearly contradicts the United Nations ideals of respect for human rights and human dignity”. Rumors swirled that the African group had endorsed Tedros – a former health and foreign minister of Ethiopia – over other African candidates for the top post, “without any real regional contest or debate” as Mugabe was head of the African Union (AU). The allegation however does not hold up against the fact that Mugabe at the time of Tedros’ election (May 2017) was no longer heading the AU (President Alpha Conde of Guinea is the chair since January). This is of course the kind of news that resonates with gossip and conspiracy lovers, but unfortunately it blurred the progress achieved at the Uruguay Global Conference.

So what happened in Uruguay?

The Conference focused on public health issues related to poor diet, smoking and physical inactivity and resulted in the endorsement by participating governments (mostly from the region) of the outcome document known as the “Montevideo Roadmap 2018-2030 on NCDs“.

The Roadmap starts with the observation that “one notable challenge for the prevention and control of NCDs is that public health objectives and private sector interests can conflict.”

How to solve this conflict?

The language of the document is highly diplomatic, calling for cooperation rather than confrontation. It speaks of “aligning” private sector incentives with public health goals; of going “beyond health” and “coordinating upstream action across sectors, including agriculture, environment, industry, trade and finance, education and urban planning, as well as research”. The food industry was “encouraged” to provide “healthier options that are affordable and accessible for all and that follow appropriate nutrition facts and labelling standards.”

The language is stronger only when dealing with the tobacco industry (highlights added):

“Recognizing the fundamental and irreconcilable conflict of interest between the tobacco industry and public health, we will continue to implement tobacco control measures without any tobacco industry interference.”

The Conference secretariat reported that “several countries are currently revising regulations concerning product packaging and advertising, while also pushing for lower salt, sugar and fat contents in manufactured products and related measures.”

However not all participants were happy. There was too little said about what could be done in the sectors “beyond health”, particularly trade and finance. Some oncological associations regretted not enough was done to fight cancer and called for cancer-specific targets.

The Montevideo Roadmap will go to the next WHA and turn up at the UN General Assembly in 2018 when it will be discussed by the third High Level Meeting on NCDs. To appreciate what this means, it helps to know the backdrop of WHO action to fight the NCDs over the past twenty years.

Two Decades of WHO Fighting the NCDs

Since the establishment of a global strategy on noncommunicable disease prevention and control in 2000, several policy steps were taken, building on each other, notably:

- a Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, dubbed the “world’s first modern-day global public health treaty” that entered into force in 2005 when it was signed by 168 WHO member states – today the total number of countries that are full parties are 173 plus the European Union while the US is a signatory but not yet a “party” to it (and with the Trump administration, it is not likely to happen anytime soon);

- a non-binding Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health (DPAS), endorsed at the WHA in May 2004;

- a Political Declaration of the UN General Assembly on NCDs in 2011, giving its seal of approval to WHO action in this area;

- a Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020 and

- in 2014 a Global Coordination Mechanism to fight NCDs (GCM/NCD), with some 300 participants, including “non-State actors”. This has led, inter alia, to the production of useful “discussion papers” to “explore the impact of market and commercial factors”, for example identifying the bottlenecks to equitable access to essential medicines and basic health technologies for NCDs.

All this culminated in 2015 with the formulation of one of the Sustainable Development Goals, SDG 3 focused on health issues, thus fully integrating WHO action into Agenda 2030.

The latest development is the establishment of a new global high-level commission on NCDs, announced by the WHO Director General on 10 October 2017 with the broad aim to identify “innovative ways to curb the world’s biggest causes of death and extend life expectancy”. This interestingly expands the range of WHO action, going beyond NCDs to include “suffering from mental health issues and the impact of violence and injuries.”

The complexity of global plans and strategies, the multiplication of high-level meetings and commissions that have unfolded over time in the WHO can be mind-boggling. Coupled with chronic under-budgeting as member countries have repeatedly refused to increase their contributions, WHO has been pushed into a corner.

At times, with tragic results, as in the case of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa that caught WHO ill-prepared, with only two staff members monitoring this kind of health threat at its Geneva headquarters – a result of draconian budget cuts from member states.

SEE RELATED ARTICLE: EBOLA CHALLENGES THE WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION by Claude Forthomme

The decentralized structure of WHO, giving a large degree of autonomy to regional offices compound the problem, slowing central management and policy formulation.

Getting Things Done with Support from American Philanthropies

Paradoxically, the very weakness in WHO structures and budget has opened the door to action from civil society and the private sector. The support WHO has received from Bloomberg Philanthropies and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in its fight against tobacco use has been exemplary.

Michael Bloomberg, when he was Mayor of New York City, made one of the largest donations in the history of WHO. Given the success of tobacco controls in New York City, he felt this was a scaleable endeavor for the world and gave $375 million to global efforts on tobacco control. The Bill Gates Foundation also came onboard in 2008 with a $125 million donation.

Now, with several years of experience through WHO collaboration with the Bloomberg initiative and the Gates work in Africa, we see the results.

Tobacco control measures have proved both affordable and effective, making a real difference in tobacco use. A 2011 WHO report monitoring the tobacco epidemic was the first to show that more than 1 billion people were covered by effective tobacco control measures since 2008. For example, Uruguay, that has some of the toughest tobacco control laws in the world, was the first country in South America to ban smoking in all public and workplaces, like the ban on smoking in New York City. And its healthcare system offered counseling and support to the population. Uruguay was able to demonstrate a remarkable 25% reduction of tobacco use in adults between 2006 and 2009.

The latest WHO monitoring report (2017) found a dramatic increase in life-saving tobacco control policies over the last decade, with 4.7 billion people – 63% of world’s population – now covered by policies such as strong graphic warnings, smoke-free public places, and other measures.

In the Photo: WHO infographic

But WHO is also looking at other strategies to beat NCDs.

Moving Closer to the People

WHO has equipped itself with the means to reach out to civil society at large. A major way in which WHO does this is with the “nine voluntary global NCD targets”, working closely with its expert networks. The voluntary targets have a shorter timeline than Agenda 2030 and are set for 2025; they come with concrete policy briefs, technical guidelines and infographic materials to sustain “campaigns for action” at country level.

In the photo: An example of NCD campaign material provided by WHO Photo Credit: WHO

The idea is to raise awareness among member countries that effective and affordable measures can be taken to improve health and protect against NCDs, taking aim at the four risk factors, tobacco use, harmful use of alcohol, unhealthy diets and insufficient physical activity.

In the Photo: Increased physical activity will support global efforts to beat NCDs Photo Credit: WHO

Since 2016, WHO has even set up a portal, NCDs&Me, to “show the human face of NCDs” where people can share their experience, take a stand and support each other. Online activism is also encouraged, for example with the hashtag #beatNCDs and posters to spread the word on social media.

Can Modifying Lifestyles Beat NCDs?

Can Modifying Lifestyles Beat NCDs?

The idea of focusing on four risk factors – tobacco use, alcohol, physical inactivity, unhealthy diets – to fight NCDs is central to WHO action, yet not everyone rallies around it, not even within the UN system. One interesting criticism at the Uruguay Global Conference came from UNDP, the UN agency tasked with financing development aid. While UNDP manifested full support for the Montevideo Roadmap, it called for “greater attention across the UN to address pollution, mental health and road traffic injuries.”

This is, of course, what the new high-level Commission on NCDs will do.

But the road ahead is tough. It means going beyond modifying lifestyles and addressing the underlying causes of NCDs. That will require more basic research. And it will also require prioritizing that research, focusing first on the causes of the more important epidemics affecting humanity.

As of now, of all the epidemics threatening public health, none is more important, growing more explosively and more deeply linked to other NCDs than the obesity epidemic. Curbing and defeating obesity should be our prime concern, it threatens our children, putting at risk future generations.

Expect a fight from the food industry. Research may well unearth causes that will make certain private interests very unhappy. The food industry is notoriously inclined, like the tobacco industry before it, to fund research intended to demonstrate that its sugared drinks are safe and do not contribute to obesity.

This will require from WHO and all its networks and partners that they adopt the same position that is taken with respect to the tobacco industry: Necessary research and control measures must be pursued “without any interference” from the food industry – to use the language of the Montevideo Roadmap.

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM – Cover Photo by Dan Gold