Women are generally perceived as victims of violent extremism, terrorism, and armed-conflicts. This is largely true whenever women are forced to join violent groups or are abused in various ways in conflict and post-conflict zones. Here violence against women multiplies exponentially, including trafficking in women and girls who are forced to take on domestic and sex work for extremists and militants.

Women of different age, ethnicity, religion, and socio-economic background, however, also join such groups voluntarily for a whole spectrum of reasons. Here I shall explore the roles of women and girls in violent extremist and armed groups and what pushes them to take on these roles; the often overlooked role of women as peacebuilders and peacekeepers in their communities will also be discussed.

Women as supporters of violent extremism

Although their role in armed conflicts and violent extremist groups can be marginal compared to men’s, women do enable and support violent ideologies and groups, and have been doing it since the dawn of History. They have been involved in extreme left-wing or right-wing movements, nationalist groups, and revolutionary groups across the world in subordinate or peripheral roles for centuries.

Since the 1970s, however, women have started to take on more “soft tasks” such as logistics, political safeguarding, operations, and recruitment; and since the mid-1980s, they have had a more visible role on frontlines as combatants, a more divergent and dangerous one as suicide bombers, and – for ISIS- as mothers for the future generations of jihadists.

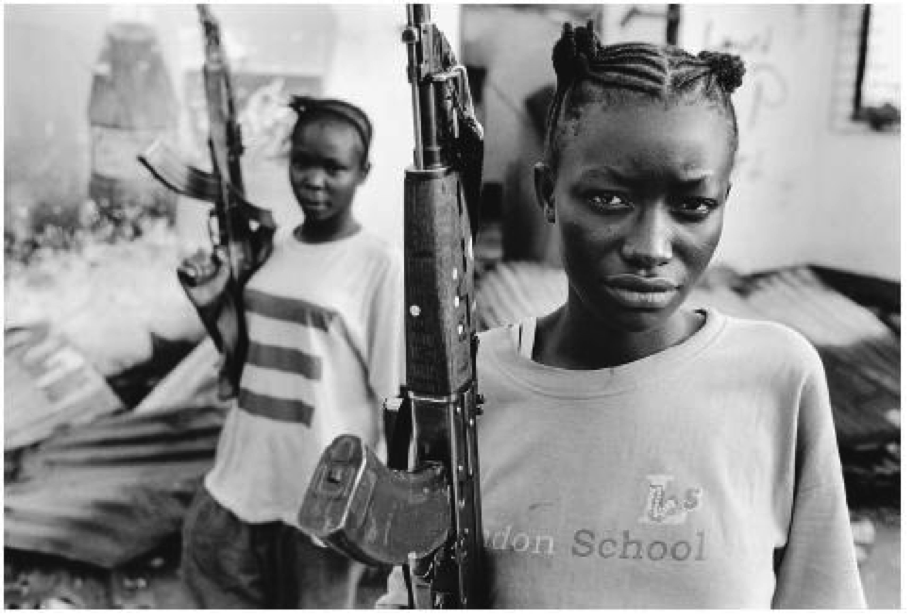

Currently, it is estimated that from 10 to 30% of members of armed groups are women and around 40% of child soldiers are girls.

IN THE PHOTO: FEMALE SOLDIERS IN SIERRA LEONE CREDIT: MEGHAN H. MACKENZIE

Despite the dominant media discourse depicting these women as “jihadist brides” or sex slaves performing “sexual jihad” due to their naivety, the picture is not so simple.

A variety of different factors make women and girls willing and proactive agents in violent extremist and armed groups. Women and girls’ participation in violent conflicts can be a result of forcible recruitment and abduction (as in the terrifying case of Boko Haram extremists who stormed a school and abducted girls at gunpoint), or it can be their voluntary decision based on certain personal experiences and incentives provided to them. The factors that push women to join terrorist, extremist, and armed groups vary from economic, political, psychological, social, and ideological.

Economic factors often are a result of inability to provide for their families due to lack of employment or decent employment; although there have been cases when educated and well employed women did join armed groups.

Political decisions stem from inability to effect sustainable changes in the current political environments in their countries due to corruption, bureaucracy, elite immunity, and other realities; or from the desire to protect their land and nation and by extension their families and home from actual or perceived enemy-state. This is the case of Arab women becoming suicide bombers against occupation of their territories by Israel; or of the all-women Dukhtaran-e-Millat religious militancy group in India’s Kashmir aiming at independence from India.

Psychological and social dimensions include individual factors such as traumatic life experiences due to marginalization and alienation from the host society, loss of identity, rape and other forms of violence, and other vulnerable areas. For women suicide bombers, for example, some of the key personal reasons include revenge for their husbands killed in a war, like the “Black Widows” in Chechnya, and fear of being tortured and raped by either party of an armed conflict such as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Sri Lanka.

IN THE PHOTO: FEMALE LIBERATION TIGERS OF TAMIL EELAM CREDIT: REUTERS

In all such situations, violent extremist and armed groups offer them an answer to their needs and vulnerabilities.

Violence against women (including early marriages) and male domination in societies are additional factors that drive women to form violent movements. They become part of terror groups where they can have a better standing as their male counterparts in armed groups may position themselves as championing women’s rights and empowerment.

For example, Sri Lankan women who joined LTTE (these women are known as “Freedom Birds”) did so to “get freedom from cultural restrictions placed on women by the Government”. LTTE offered them liberation from restrictive gender roles and progression in rank on an equal footing with the men in the group. Colombian FARC offered women financial stability and independence from men as they got to receive a salary of USD 350. Among other push factors, Indonesian women who work as domestic workers in Hong Kong chose to join ISIS for emancipation “from subservience to men.”

RELATED ARTICLE: WOMEN AND PEACEBUILDING: THE KEY TO ACHIEVING SDG 5 IN AFGHANISTAN

It gets more complicated in the case of Islamist extremist groups where Orthodox Muslim women can be offered an all-encompassing “utopian alternative to living in secular societies [that] make living as a pious and righteous Muslim impossible.”

These women move to join such groups as ISIS, Jaish al-Fatah, and Jabhat Fateh al-Sham to exercise their agency. In the ‘states’ (caliphates) these violent extremist groups create, women run gender-segregated financial institutions, education, health care, police, military, and other institutions. Women get empowered with autonomy and leading positions in the parallel system of all types of institutions of the caliphate and keep minimal exposure to men.

Although there are women who join voluntarily, there are also cases of women who joined armed groups in largely Muslim territories (e.g., the Middle Eastern countries and Kosovo) due to their dependency on their husbands or male relatives. Apart from financial incentives, they are also influenced by them through emotional blackmail and violent extremist propaganda that states that it is the ultimate duty of Muslim young women to join such groups.

Such terrorist ‘units’ consisting of a husband and a wife are a developing tactic used by extremists as they are easy to “disguise of being a family.”

IN THE PHOTO: ISIS FEMALE BRIGADE AL KHANSAA CREDIT: REUTERS

Women in peacebuilding, protection, and conflict resolution

Increased engagement in peacebuilding, countering extremism, and related activities is the answer to the participation of women in violent extremist and armed groups.

What is perhaps surprising is that women, despite being adversely affected by conflicts, have long been overlooked in prevention of violent extremism and de-radicalization efforts. They are underrepresented in official roles that work on and influence decisions on peace, disarmament, and non-proliferation.

Women, however, need to be given positions to play an active role in drafting and implementing relevant and effective strategies for prevention of extremist and other conflicts. They need to be involved in building sustainable peace by working towards justice, including in post-conflict and post-war societies.

First, they can bring a fresh perspective on the issues as a result of their gendered position and the experience of violence they have gone through, whether they have joined a violent extremist group or not.

Second, in post-conflict environments, they are often heads of households (up to 75% of the cases) which provides them with influence on the whole family and its transition to civilian and peaceful life.

Third, in many societies women are regarded as the key caregivers who then in this capacity should have more responsibility in reaching out to the most marginalized and traumatized populations, especially children, youth, and elderly.

Particular attention should be paid to working with mothers as they may play a critical role in their children’s engagement with violent extremist ideologies and help build their resilience to such ideologies and groups. Some of them have had their children join terrorist groups in the Middle East and other areas, and in many cases, they have never returned.

Such experiences position these women as some of the strongest stakeholders in understanding the processes of radicalization, prevention, and de-radicalization. This stakeholder group is – yet again – largely ignored and even mocked and attacked into silence; the organization “Mothers for Life” that unites mothers across the world to fight against radicalization of their children showcased this issue in their open letter.

IN THE PHOTO: WOMEN PEACE LEADERS DISCUSS EMPOWERING MOTHERS AS THE BEST WAY TO COUNTER VIOLENT EXTREMISM CREDIT: ROBBY JOY D. SALVERON

Finally, we have abundant evidence that when women are involved in prevention, protection, and peacebuilding despite barriers for them not to, the effect is positive, lasting, and strong.

For example, at a Muslim-majority countries seminar conducted in Indonesia, representatives from Nigeria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Indonesia shared experience showing that the influence of violent extremist groups was decreased when women got involved in negotiations and supported education spreading peaceful Islamic teachings in their communities. This helped to heal individuals and communities affected by violence, including former members of such groups.

In Venezuela, it is mothers who took the situation under their control and negotiated truce when their children got involved in gangs and were subsequently violently killed.

In Rwanda, women carved their own roles in reconciliation and economy to transition the country from the 1994 genocide to lasting peace and security.

UN peacekeeping missions show that women can deliver results that their men counterparts can’t: women can build stronger relationships with communities they work in, gain more access to information, inspire local women to enter security services, and decrease and even end sexual abuse by men peacekeeping forces.

RELATED ARTICLE: BUILDING SAFE RESILIENT URBAN SPACES

The challenge is, however, that in many societies women are still not recognized “as being on par” with men to combat violent extremism and rebuild communities when wars and conflicts end.

It goes further: Despite the UN Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism that acknowledges gender-specific needs, counter-terrorist tactics and efforts in countering violent extremism remain gender-blind.

What is left to women without much political, financial, and technical support and training is to keep leading such efforts in mostly informal ways. Arguably, it’s not much, it’s far from enough, but it’s a start. A start that needs to be cultivated and encouraged.