Once again the European Parliament and the Council are at loggerheads over the EU’s seven-year budget. The “only” difference compared to previous negotiations is that, in this case, the 2021-2027 budget is anchored to a crucial instrument for economic recovery: the Recovery fund, the 750 billion euro plan devised by the EU Commission for the relaunch of an EU in the grip of the pandemic crisis.

The latest round of negotiations between the Euro Parliament and the Council ended with a stalemate. Yet no one has an interest in wrecking an aid package essential to keep the EU economy afloat. But, for now, conciliatory approaches have been lost in the din of accusations and recriminations.

What is the dialogue stuck on? It’s the same old story. The objects of contention are those that had already emerged in the acrimonious debates that led to the agreement between the 27 EU leaders at the European Council last July. A hard-won agreement on both the composition of the Recovery fund – 390 billion in subsidies and 360 billion in loans, the latter a veritable first for the EU, a victory for the new EU Commission head, Ursula von der Leyen – and the size of the budget, approximately € 1,074 billion.

Just to clarify what is at stake here: The Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) will be the core of the EU’s new Recovery Instrument to fight the economic fallout of the pandemic. Under the RRF, 310 billion euros in additional EU spending will be allocated by the European Commission to member states based on individual Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs).

The European Parliament asked back then and continues to push now for several important points:

- more funds from sectors such as research, innovation, and health;

- a more active role in the management of the Recovery fund;

- a clear EU commitment to seek its own resources for the budget; and

- a mechanism that binds the receipt of funding to compliance with Rule of law.

These are big requests that impact decisively a text that is already the result of difficult negotiations between the 27 EU governments.

In a letter to the Members of the European Parliament, the German ambassador to the EU Michael Clauss tried to break the deadlock by proposing to increase the budget and institute stricter control of respect for the rule of law. In fact, for Germany, extending the rule of law to the whole of Europe has become a priority:

Respect for rule of law principles by all member states is an indispensable pillar of the EU. In order to strengthen this principle, a new rule of law dialogue will be introduced during #EU2020DE. Read more on our website: https://t.co/Rab1c5j5GB

— EU2020DE (@EU2020DE) October 11, 2020

But that was not enough to please the Parliament. Jaume Duch, the Parliament’s spokesman, openly criticized the fact that the extra share of funding came from the margins for unexpected needs, announcing the suspension of negotiations on Twitter on 8 October:

“Refusing to move at all is not negotiating. MEPs will come back to the table once there is a real will from Council’s side to find an agreement.” https://t.co/MzsJBRVBkG

— Jaume Duch (@jduch) October 8, 2020

The next day (9 October), Jaume Duch made it absolutely crystal clear that he felt there was still plenty of time for the negotiations, retweeting Lucas Guttenberg’s tweet:

So well explained… https://t.co/ka6f7O5TK9

— Jaume Duch (@jduch) October 9, 2020

Just for the record, Lucas Gutenberg is Deputy Director of the Jacques Delors Centre and an expert on European reform, Germany’s role in the EU, and the state of German-French relations. In a major policy brief published in June 2020, How to spend it right – A more democratic governance for the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility, he argued, along with co-author Thu Nguyen, that the proposed governance to decide on the assessment of individual RRPs going to each EU member state was essentially undemocratic because parliaments are largely sidelined. This, the authors said, should be changed to ensure necessary political ownership at both the national and European levels and thus “avoid a roll-back of EU democracy”.

Therefore, they proposed that the European Parliament get a veto over the Commission decision assessing individual RRPs and allocating funds. National parliaments should also “have a say in the adoption of the RRP of the respective member state”.

So don’t expect the European Parliament to bow down to the Council budget proposal without a fight.

And yes, Gutenberg is right about the space for negotiations. He’s being realistic about the timeline: It is indeed a very long one. He asks us to consider this:

2/ Some countries still block the start of the ratification process in the Council, making it less and less likely that ratification will be completed by January. Alas, the EU will not need to start issuing by then. The first RRF payouts will likely not happen before the summer.

— Lucas Guttenberg (@lucasguttenberg) October 8, 2020

In short, no European country should expect any payments from Brussels before June 2021.

So here at last the heart of the problem is clearly revealed: Nationalistic interests are the obstacles. As usual, nothing new here in a Europe torn apart by proud nation-states that won’t give up an inch of their sovereignty, even if it is for the common good.

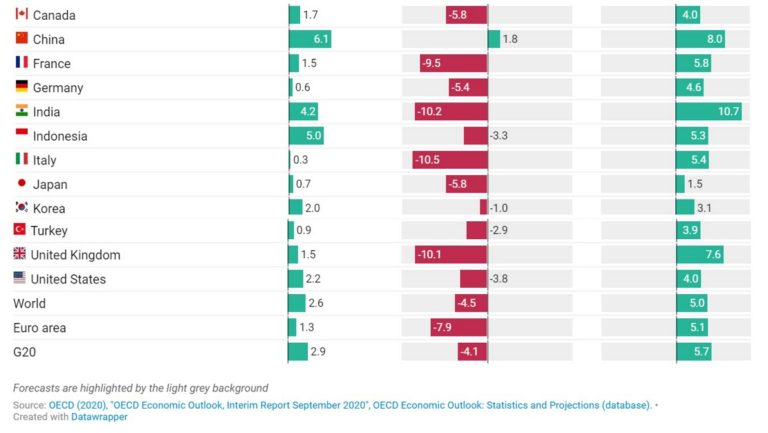

And what is behind nationalistic interests besides populistic impulses à la Viktor Orban, Marine Le Pen and Matteo Salvini? The Economist has no doubts about who and what is behind: National business interests. Take a look at its fascinating article describing the economic winners and losers from the COVID-19 shock – and yes, China is the big winner according to the OECD’s September 2020 Outlook Report: expect China to grow, the only country to do so in both 2020 and 2021:

The Euro area, as shown above, is expected to grow slightly better than the U.S., +5.1% as against a paltry 4%, an unusual situation for America that historically has always rebounded better than Europe: This is clearly traceable to the Trump administration’s mismanagement of the pandemic.

To explain Europe’s lackluster performance, the Economist unequivocally points the finger at business: Even before the pandemic crisis, it notes, “France and Germany were already embracing an industrial policy that promoted national champions. If Europe sees the pandemic as a further reason to nurture a cosy relationship between government and incumbent businesses, its long-term relative decline could accelerate.”

So don’t be surprised if the spokesman for the German EU presidency, Sebastian Fischer, judged it “regrettable” that Parliament missed (read: rejected) the “opportunity to continue negotiations on the EU budget”. Business interests are indeed powerful in Germany. As they are in all the European economies.

Business interests are supported by neo-liberalism, the famously destructive ideology that was born in two bestsellers, Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom (U. of Chicago Press, 1944) and Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom (U. of Chicago Press, 1962). The core concept was memorably expressed by Friedman in a widely read 1970 New York Times Magazine article:

There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.

Predictably, businessmen loved this. No social responsibility for anyone except themselves. Here at last they had a green light to exploit their workers and gouge customers to their heart’s content.

The theory that “government was the problem” because the government was supporting public health and education was enthusiastically embraced by two towering conservative politicians who changed the world (and made it worse, starting the spiral into income inequality and social injustice): Ronald Reagan in the U.S. and Margaret Thatcher in the UK. Both countries have still not recovered from the neo-liberal shock, displaying higher levels of income inequality than the rest of Western Europe. Unquestionably, COVID-19 is making it worse, bringing home the tragic fact that without a strong investment in public health, poor people die like flies.

But in other ways, continental Europe has hardly fared better.

As the economist Philipp Heimberger recently pointed out in a Huffington Post interview, countries like Italy were forced to function below their natural level because of the austerity policies imposed by the EU Commission in Brussels over the last ten years. Such policies (inspired by Germany’s insistence on balanced budgets) unfortunately cut deeply into needed investment into education and public health.

As a result, when COVID-19 filled hospitals in Lombardy and medical equipment was insufficient (especially ventilators) in the first pandemic wave of March-April 2020, Italian doctors were forced to make incredibly difficult and painful choices between who to save and who to let die. And it was not just Italy that was affected, but the whole of Southern Europe and a raft of European countries that followed neoliberal policies too closely for their own good.

The fundamental question now facing all Europeans is this: Will neo-liberalism continue to rear its ugly head in Brussels and stalk the corridors of the EU Commission?

Or will European politicians finally listen to the rising new school of economists (see the video above, one of the new school’s major exponent, Mariana Mazzucato) that calls for a radical change in the role of government in the economy and recognition (finally) that the private sector simply cannot deliver?

In the featured image: Ahead of the EU budget summit on 20 February, European Parliament members discuss EU priorities for the next financial framework with Council and Commission – here with Ursula von der Leyen. Europa. Eu news article here. Source: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2020 – Source: EP