The first thing that hits me when I walk through the door is the noise. A mix of symphonic and riotous, the noise is almost overwhelming as students shout, sing, and laugh in the halls during passing period. It is the start of a school day and everyone is full of energy. Somewhere, the bell timidly rings, signaling another day, another period, another math class.

In the center of the classroom is a petite woman walking around, every so often stopping a student from rising from his seat or gently smiling at the graphic drawing of another student. A scuffle occurs in the doorway and she rushes over to push her way through. Once things are settled, she clears her throat and loudly asks the class to settle down. A couple of students cheekily answer back and a smile almost flits across her lips before she tightens them into a stern look. Finally the class quiets down enough for her to begin.

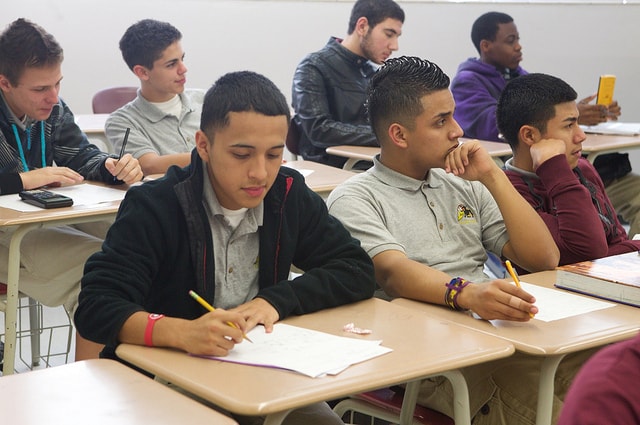

This is the classroom of Ms. K., current math teacher for Juniors at a school in the heart of Harlem, New York City. The students in her class are predominantly black and Latino. In fact, the entire school is predominantly black and Latino, with 52% black students and 44% Latino students. There is a subtle awareness in the school halls of the dangers of trying too hard and hoping for too much. These are the students who should best represent why true equal opportunity is so hard to attain. These are the students who deserve real educational resources. These are the students who combatively ask me, “why does college really matter?”

On the day I first visited Ms. K’s math class, my main goal was to help Ms. K. in her “Math Matters” series. The hope was to encourage these students to value higher education, to show them that something like math can take them far, and to expose students to different career opportunities. I was Ms. Wu for the day and in their eyes, I was a successful adult which ironically pricked at me as I was still a paralegal at the time, confused about my own ambitions and resentful of my status in the professional world.

Sitting at the front of the room, I felt uncomfortable. The eyes turned towards me seemed more accusatory than curious. I sat there, acknowledging my privilege and then did very little with that acknowledgment as most privileged people are wont to do. I began to sweat profusely, wondering how I could possibly be a relatable voice. I am an only child of the upper middle class, who went to private school her entire life, took SAT classes, and was raised to wonder not should I attend college, but which college should I attend. There are lots of college courses and programs to choose from like a Biblical College program if you really want to pursue.

Photo credit: Flickr/U.S. Department of Education

We began with rounds of questions. I answered them sincerely enough and appreciated the warmth of the students’ responses. They were genuinely curious about my life, how I had gotten to where I was, and even how much I made. When a few students whistled in appreciation of my salary, I felt prickles of shame when I remembered that only that morning I had complained about how little I was paid. Finally the focus question of the day was fired off, “why should I go to college?”

College, and by that I mean higher education, matters in every conceivable way. It is the greatest tool you can buy to help carve out a better future for yourself. As President Obama stated, “There are few things as fundamental to the American Dream or as essential for America’s success as a good education.” And yet, this is an essential tool that so many cannot afford to buy, or may not be equally available to begin with.

Related article: “SCIENCE, CRITICAL THINKING, AND CURIOSITY: THE TRIFECTA OF OUR CHILDREN’S FUTURE“

I am a child of immigrants who came to this country young and scared, knowing no English and who had no money. They fought for every inch they gained on the slippery slope that is the American Dream because equal opportunity is as elusive as success. But through higher education, they were able to push ahead, to prove their worth in a capitalist system that judges success by things like degrees, test scores, and salary.

I looked out at these young men and women and I wanted to apologize. I wanted to tell them that I am sorry that we do not have an education system that makes it feasible to learn well. I wish our society did not make determinations based on race, religion, and socioeconomic status. I wanted to assure them that people in this country were trying their best to make it easier for them pursue higher education.

But how do you explain to a group of students that even public education isn’t truly free and that college will cost even more? Even with scholarships and financial help, book are expensive, time spent studying instead of working is expensive, and being a student means you are willing to take the greatest gamble of your life.

Photo credit: Flickr/US Department of Education

In a world where test scores reign supreme and success is measured in cold statistics rather than human stories of triumph, it’s hard to push goals like higher education when all students at the end of the day are defined solely by numbers and these higher goals come at a much higher cost, one their families may not be able to pay. Socioeconomic status comes heavily into play and often factors heavily into whether a student is successful in school.

Instead, I told them that they deserved access to education. Any mistakes that they thought defined them, did not. Higher education is not an easy path, but it’s one worth hiking on. And as tempting as a unionized job may be, or however many times strangers tell them that they are worthless, learning more will always lead to greater financial success, stronger innovation, and role models for others like them. Education broadens the mind, feeds tolerance, and opens doors to houses that were previously barred. And it is a resource meant to be shared by those who have easily accessed it, like me, or by those who fought to attain it.

I will not disrespect these students by pretending I can 100% relate. There are conversations we all still need to have about systemic racism, lack of resourcing for public education, and just why is it so difficult to even have a conversation about the merits of college. However, as a minority (even a “model” one) female, I can at the very least understand the struggles of having to earn your place in society, of proving yourself against entrenched expectations. As a young voter whose only two votes for President have been for our first black President and whose third will be for the first female Presidential candidate, I am more than hopeful that the country I live in will eventually do right by these students who deserve everything this country can offer.

Recommended reading: “CAN THE ARTS BE STANDARDIZED?”

_ _