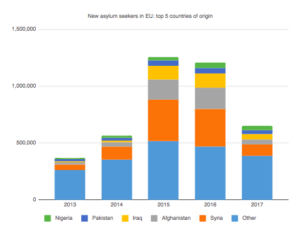

Between 2013 and 2017, the 28 member states of the European Union provided protection to roughly 800,000 Syrian refugees who arrived in the EU and applied for asylum. In total, 1.7 million asylum seekers from a diverse range of countries, predominantly in the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, were granted a right to stay in the EU over these five years.

Instead of taking pride in this achievement, European societies and the political leaders of the EU are today deeply divided over asylum and refugees. After strong inflows of protection seekers during the so-called “European refugee crisis” in 2015-2016, one member state after another is now trying to close its doors. Yet this is not going to solve the problem. The real issue lies with the EU policy on asylum: a number of long-standing deficits and injustices are far from being resolved.

At the core of the European refugee crisis, there are three main problems:

(1) There is a lack of legal entry pathways for protection seekers to reach the EU;

(2) The member states have no system to share the burdens and responsibilities arising from the reception of asylum seekers among each other; and

(3) The chances of asylum applicants to actually receive protection vary greatly depending on their point of entry to the EU

IN THE PHOTO: European Council meeting, 22-23 June 2017. CREDIT: European Council via Flickr

Issue 1: lack of legal pathways to Europe for refugees

The need for the EU member states to cooperate on migration and asylum is a result of the principle of free movement of people between these states, which is considered one of the great achievements of European unification. EU citizens who find work in another member country are free to settle there without asking for permission. As the EU thus functions as a common mobility space without internal borders, it needs common rules on who is allowed access to EU territory from outside. This is why a common policy on external border crossings and short-term entry visas was put in place.

While Schengen makes life easier for mobile EU citizens, it poses an almost insurmountable obstacle to people who try to reach Europe to seek protection from political persecution, war and conflict. All relevant countries of origin of asylum seekers are subject to visa requirements. Rather than giving access to one country only, “Schengen visas” are normally valid for all states participating in the free movement area. Schengen visas are not granted, however, if EU embassies or consulates have reason to believe that a visa applicant will not be willing to return to his or her country of origin when the visa expires. Schengen visas are strictly temporary. Only in exceptional cases, individual states are entitled to grant entry visas for humanitarian purposes. The EU visa regime thus serves as an effective barrier to unsolicited migrants, including protection seekers.

This leaves them with the option to seek legal access as workers, family members of people already residing in the EU, or students. But as the conditions for such access are often difficult to fulfil, and not always easy to understand as each member state has its own rules on labour, family or student migration, getting a long-stay entry permit is seldom realistic. And if an airline or other carrier takes people without the necessary entry permits into Europe, they are liable to sanctions.

It is, therefore, no surprise that refugees and migrants try to reach Europe through irregular and often very dangerous pathways, putting their lives in the hands of criminal smuggling networks. Over recent years, several thousands have drowned or disappeared in the Mediterranean; countless others have been incarcerated, exploited and abused before even reaching European shores.

IN THE PHOTO: Heidelberg, Germany. CREDIT: Photo by Roman Kraft

So far, the institutions of the EU have been unable, or unwilling, to address this issue.

A more systematic approach to granting legal entry visas for humanitarian and protection purposes has been ruled out because political leaders are afraid of the possible consequences of better legal access in terms of rising numbers of immigrants.

The only established legal pathway for people in need of protection is state-organised resettlement, whereby refugees are selected in transit countries and brought to Europe. Such programs have remained relatively limited, however. In 2017, all EU countries taken together resettled just above 24,000 refugees, while more than 700,000 people arrived on their own as asylum seekers. If the EU were to establish credible and durable protection policies, it would need to expand resettlement possibilities considerably and open other possibilities for refugees to reach the Union in an orderly manner.

Issue 2: Developing a Common European Asylum System

For almost 20 years now, the EU has been trying to establish a Common European Asylum System (CEAS). Today, this system includes a complex series of legal acts, which regulate the determination of the member state responsible for examining an asylum application (the so-called Dublin regulation) and provide minimum standards for the reception of asylum seekers, asylum procedures, and criteria for the recognition of non-EU nationals as refugees or people in need of subsidiary protection.

These laws are supplemented by further legal acts that go beyond asylum in the narrow sense, such as common rules for the repatriation of persons obliged to leave the country (for instance, rejected asylum seekers and visa overstayers). In 2016, the European Commission launched a process to reform and strengthen the joint legislation as well as common institutions such as the European Asylum Support Office and the Border and Coast Guard Agency Frontex, while at the same time promoting closer cooperation with major countries of origin and transit, to limit irregular inflows.

Apart from the problem of legal access to protection, the main issues currently debated are a fairer sharing of responsibilities among the EU member states for the intake of asylum seekers, and a more uniform asylum decision-making practice.

Issue 3: Unequal responsibility-sharing for asylum seekers across the EU

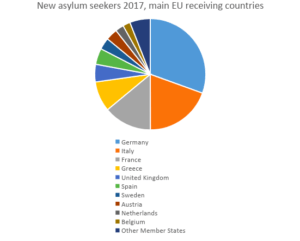

The number of people who have applied for asylum in the individual member states of the EU over recent years clearly demonstrates that more equitable responsibility-sharing is an urgent necessity. During the European Refugee Crisis in 2015-2016, some countries were disproportionately affected by quickly and strongly rising numbers of protection seekers, while others barely noticed any such developments.

In 2015, according to Eurostat, the highest number of new asylum applicants was registered in Germany (with 441,800 first time applicants), which represents a share of 35 percent first-time applicants in the EU that year (1.25 million). Hungary came second with a share of 14 percent, followed by Sweden (12 percent) and Austria (7 percent). Compared with the population of each EU member state, the highest number of registered applicants in 2015 was recorded in Hungary (17,699 first time applicants per one million inhabitants), ahead of Sweden, Austria, Finland and Germany.

SOURCE: EUROSTAT

At the other end of the scale, Croatia only had 34 applicants per million inhabitants, Slovakia 50, Romania 62, Portugal 80 and Lithuania 93. Thus, the countries that are most affected by arrivals of asylum seekers are on the one hand those that are geographically situated at the main entry routes to Europe.

On the other hand, even remoter countries such as Sweden had disproportionately large influxes, predominantly due to their positive reputation among protection seekers. In 2017, Greece recorded 5,295 new asylum applicants per million population, while Slovakia only registered 27. Germany had 2,402 per million inhabitants, and Sweden 2,220.

Such imbalances have had consequences.

As the Swedish reception and accommodation system for asylum seekers collapsed due to the extraordinary number of arrivals in 2015 (roughly 163,000), the government in Stockholm introduced border and identity checks on people trying to reach the Scandinavian country, and to restrict the right of people in need of protection to permanent residence rights and family reunification. The new approach was to align the Swedish standards of protection to the EU minimum level.

This clearly shows that the lack of responsibility-sharing among the various member states of the EU triggers a “race to the bottom”. Relatively attractive destinations try to become less popular, if not openly hostile, to refugees. While Sweden took a disproportionate share of 12.4 percent of all asylum seekers coming to the EU in 2015, its share was only 3.4 percent in 2017.

How to devise an equitable responsibility-sharing mechanism among the member states for the intake of asylum seekers therefore represents one of the key challenges of political leaders in the EU. If all EU countries would take a fair share, taking into account their population and economic performance, the EU would be more resilient to rising inflows.

The European “Asylum lottery”

For a responsibility-sharing model to work, the EU also needs to address another problem: fairness towards refugees. Ideally, this would mean that they have equal chances to receive protection irrespective of where they arrive. While an overall trend towards higher protection rates can be identified across almost all its member states over recent years, not least due to increased numbers of asylum seekers from war-ridden countries such as Syria, the asylum decision-making practices regarding many different countries of origin still vary enormously.

The cases of Afghanistan and Iraq, two of the main countries of origin of asylum seekers in Europe, have recently been particularly illustrative of this problem. In 2016, the chances for an asylum seeker from Iraq to receive protection in Hungary and the United Kingdom was below 13 percent, compared to 100 percent in Spain and Slovakia.

During the first half of 2017, Afghan nationals had a 46.3 percent chance of receiving protection in Germany, the main destination country within the EU. Austria (49.5 percent) and Sweden (48.2 percent) were close to this rate. By contrast, the recognition rate for Afghans was close to 0 percent in Bulgaria, below 10 percent in Hungary and below 20 percent in Denmark. At the same time, Italy, France and Luxembourg were much more generous, with protection rates well above 80 percent.

SOURCE: EUROSTAT

As the EU does not want asylum seekers to apply for protection in several member states, it has developed a system of determining the responsible member state for each asylum case. In most cases, the country of first arrival has to process the application. But as long as the chances of receiving protection vary between the various member states as much as they do, it remains unfair to allocate asylum seekers to a country where they would most likely be rejected, while they would receive protection if allocated to a different state.

Is the EU able to address the flaws of its asylum policy?

These three fundamental flaws of the asylum policy in the European Union are interdependent and consequently complicated to address.

In the absence of legal pathways to protection, asylum seekers resort to illegal border crossing, which exposes a handful of “frontline” EU member states, particularly Greece and Italy, to disproportionate pressures. As there is no system of allocating protection seekers to the various member states on the basis of a fair distribution system, states adopt restrictive approaches, lowering their protection standards and tightening access to decent living conditions and integration opportunities for new arrivals. Finally, the fact that asylum decision-making varies greatly between the various states means that refugees resort to “secondary movements” in search of a chance of being allowed to stay.

A political process to reform the Common European Asylum System has been initiated against the backdrop of the chaotic refugee situation in 2015 and 2016, but its outcomes are yet far from clear. While some countries strongly advocate for a comprehensive responsibility-sharing system, others oppose binding commitments.

As for legal entry pathways, resettlement commitments have been modestly expanded in some countries, but humanitarian visas or similar instruments have been ruled out for the time being. Developing a common approach to asylum decisions is a process that requires time and patience, but joint processing exercises (where officials from several countries examine asylum cases together) and the production of common country of origin information (which serves as a basis for asylum adjudication) need to be intensified.

Recently, Europe has invested a lot into preventing irregular inflows of protection seekers. An agreement with Turkey has reduced refugee arrivals to Greece. Obscure deals with Libya, and support for the local coast guard system have decreased crossings to Italy through the Mediterranean. In Niger, the EU spends considerable amounts of money to hinder Africans from migrating further towards the North.

As a result, the number of asylum seekers that arrived in the EU in 2017 was only half the number recorded in 2016. European leaders have also proposed to create asylum processing centers beyond the (strengthened) borders of the European Union, outsourcing asylum to Africa. How exactly such centers would work and who would be responsible remains to be clarified.

An obvious risk is that the lower number of arrivals takes away pressures on policy-makers to find feasible, long-term solutions to the three aforementioned main issues. Whether the EU will be better prepared when a new migratory crisis hits, is far from clear.

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM.

FEATURED PHOTO CREDIT: Frode Bjorshol via Flickr