After having witnessed thousands of people stampede through their local supermarkets amid COVID-19’s outbreak, stripping aisles bare whilst willingly queuing in line for hours, one might question how such a state of panic arose particularly within advanced societies.

Some may claim that desperate times call for desperate measures, implying that panic buying may be an appropriate and proportional response to the circumstances at hand: a lockdown, in this case. However, Steven Taylor, a professor and clinical psychologist of British Columbia, makes a profound distinction between disaster preparation and panic buying to help understand the uniqueness of such current events. When preparing for a flood, for instance, people have a rough estimation of what they need, whereas panic buying is primarily “fuelled by anxiety and a willingness to go to lengths to quell those fears,” says Taylor.

When people feel uncertain, they tend to focus on things that bring them certainty,

— Neuroeconomist Uma Karmarkar.

The mass hysteria regarding COVID-19 has significantly fuelled a growing anxiety amongst the public. For most “supermarket raiders,” panic buying provides a coping mechanism for the helpless feelings that such an abnormality generates. Somehow, an essential item like a toilet roll provides more of a symbolic gesture of control, rather than a practical necessity.

“When people feel uncertain, they tend to focus on things that bring them certainty,” explained neuroeconomist Uma Karmarkar. But is panic buying a natural response to uncertainty? Or are factors present within a particular society that lead to such behaviour?

It is fair to assume that a more developed and secure country would bear a society far more equipped to maintain a degree of civility. Thus, it comes as somewhat of a surprise that panic buying has been most prevalent amongst the more developed parts of the world.

A recent Zhejiang University study explored the psychological causes of panic buying following a health crisis, highlighting the importance of social capital, or social trust, and breaking it down into two key aspects; trust in a community that bears a collectivist culture of generosity and selflessness, and trust in the government in providing relief and security. The study found that high levels of social trust lead to a more cooperative and considerate society when faced with a crisis.

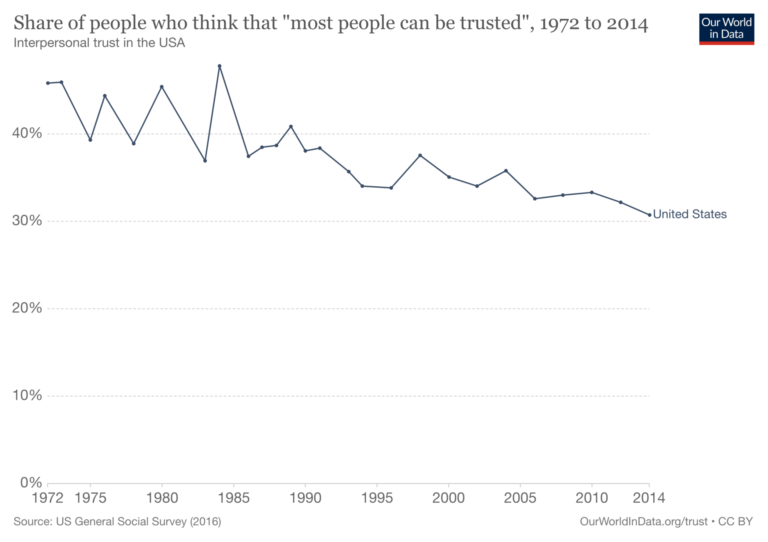

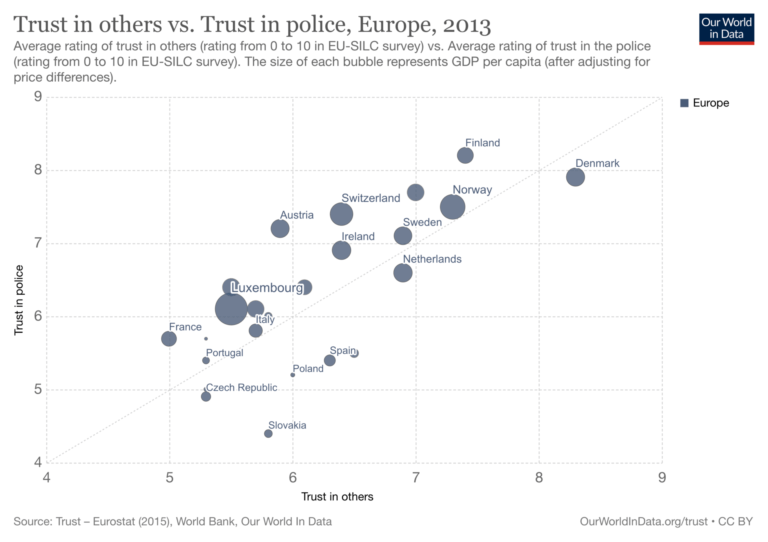

Further analysis revealed that the U.S. is experiencing a staggering 40-year low with regards to the social trust amongst its citizens. Several European countries were also found to have a stronger trust between citizens and the police than amongst the citizens themselves. What do such findings then reflect about the culture of modern society and its relative failure to cooperate in times of duress?

Those within advanced societies are far less vulnerable to threats upon their livelihoods than those living in deprived, or conflict-ridden territories. People living in a city like London may have a relative feeling of safety and trust upon a government to maintain its law and order. However, when such support is readily available from a given government, the reliance upon community may diminish.

Yet those from a more deprived or hostile location, for instance, a village in South Sudan, may be more inclined to withhold their trust from those beyond their community, further reinforcing communal ties. This cultivation of community, which was once the very bedrock of western civilisation, appears glaringly absent within modern society.

Additionally, communal ties in modern societies have become progressively trivial in this consumerism era, with the embedment of its notion ‘’material gain reflects success’’ into the fabric of modern culture largely contributing to this progression. More can be made on whether consumerism is a cause or result of the disintegration of community, or possibly both. Irrespective of this, however, it certainly has exacerbated individualism.

Related Articles: Consumerism Is Passé | Sustainability in a Consumer-Besotted World

Technological advancements have also contributed to the collapse of social atomisation. Means of communication and transportation have allowed individuals to live independently from a particular community, thus breaking or preventing any communal ties of residence. Due to a rise in globalisation, individuals tend to adopt the norms and customs of whichever locale they reside in, thus inhibiting the development of a distinct social identity.

In wealthier areas, most citizens commute beyond their communities to earn a living in a particular working hub like Canary Wharf. Consequently, these workers are far less likely to develop close relations with their neighbours as a majority of their relationships are often developed miles away from their homes, leaving behind a somewhat disconnected community.

Yet those residing in the villages of Bangladesh, for example, make do with what they have within the confines of their community, and are perhaps ‘’saved’’ by the role their community has kept for them. Subsequently, when a calamity that is beyond the government’s containment befalls, those in more advanced parts of the world are often compelled towards individualistic pursuits when left with no one to turn to for support, whereas those in more deprived regions still have their communities to rely on.

Privileged luxuries of governmental security and technological advancements, accompanied by an individualistic culture, help keep social trust at an all-time low. As a result, we have experienced unprecedented levels of panic buying from those who can afford such luxuries, with little to no regard for their more vulnerable neighbours who may be in as much, if not more of a need of such essentials – quite out of line with Composer John Powell’s advice:

To live fully, we must learn to use things and love people, and not love things and use people.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. —In the Featured Photo: Bare shelves due to panic buying in the Giant supermarket at the Franklin Farm Village Shopping Centre in the Franklin Farm section of Oak Hill, Fairfax County, Virginia during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons