Editor’s Note: In order to respect the author’s long career, the Impakter team has not intervened with any edits for this opinion piece.

The morning after the US 2016 election I awoke in a panic gasping for breath. The reason, apart from the obvious, was climate change. It is, to anyone with an even modestly functioning brain, the most important issue we have ever faced since humans have inhabited the planet.

For the past 17 years I have lived in Italy. The heat wave that swept across Europe that first summer of 2003 was reminiscent of a Twilight Zone episode from the last century: The sun gets closer and closer to the earth and eventually burns up everything. The heat that summer was hallucinatory. With no air conditioning and not even a fan I spent my days in the dark, windows shuttered against the enemy. Hanging the laundry on the line was a major challenge; useless to climb back up to the third floor of my ancient building as within ten minutes all the laundry, including heavy 19th Century hemp sheets, would be bone dry. Better to wait it out in the shade.

Thousands of people died in France that summer. Italy didn’t bother to count. My personal cooling system consisted of two full hot water bottles, frozen, one on my head the other on my chest so I could sleep at night. My Italian neighbors, for whom the use of ice is an anomaly, were horrified; they issued stern warnings about imminent death from a frozen heart. I, a New Englander by birth, was more worried about my heart being cooked to a fare thee well.

That summer was considered a fluke. Summers on the Bolognese pianura were hot yes, but not Hell on earth.

The eleven summers that followed were normal by suffocating Bolognese standards, but in 2014 I moved to Tuscany and in the five years since, the changes in climate, not just weather, have been staggering. The summer of 2017 was equal to that of 2003, again requiring closed shutters, darkened rooms and frozen hot water bottles. I could safely leave the house at 5 AM and again at 10 PM, but when I had to leave for groceries, the interior of my car was so hot I needed gloves to touch the steering wheel. Twice, snakes entered my home seeking refuge from the heat. One was small and green, the other black and huge. I didn’t throw welcome parties, but felt such pity I allowed them to stay until evening when I showed them to the door.

Then came the pyrotechnic summer of 2018. Portugal was in flames; so was California. In Chianti, where I live, the temperature soared daily to over 100 degrees in the shade and well above that under the over promoted Tuscan sun accompanied by 80 to 90 percent humidity. Three days in a row the temperature hovered at 122 F. Going outside after 9 AM meant risking instant dehydration and possible heat stroke; staying cool meant once again closing my windows and shutters at dawn and living like a mole for the next sixteen hours. Walking from the living room to the kitchen felt like wading through hot cream soup.

I desperately searched Netflix for something, God anything, distracting to watch. And suddenly there it was, a time traveling nurse from the 40’s hooking up with a kilt clad swaggering 18th Century Scot, probably the most perfect man ever created by a writer of fiction. Outlander.

I am an ardent Outlander fan for a multitude of reasons: The potent love story at its core, the factual history that envelops and informs it, the stunning Scottish landscape even when it’s pretending to be North Carolina in 1767, the attention given to detail in the exquisite costume and set design and decoration, and the stellar quality of acting and writing.

But there is another intriguing quality that keeps me watching and that’s everything that’s not there. Once we slip back two hundred years into the past there is nothing of what we have come to rely on to sustain our 21st Century lives. There are no cars, no fossil fuels, no agribusiness, no trains, buses or planes. No electricity, running water, phones, smart or dumb, no internet or indoor plumbing. No ocean destroying plastic. Nothing is mass produced and everything is recycled, reused, mended, fixed or handed down. Little if anything is thrown away. There is no planned obsolescence to force us into runaway consumerism.

Apart from the time travelers no one misses what isn’t there. Yet little is noted by those travelers regarding the pristine quality of the earth. A missed opportunity perhaps, because by the time they all find themselves back in the 18th Century where the Industrial Revolution hadn’t even begun, the first catastrophic oil spill had already leaked 88 gallons of crude off the coast of the Scilly Islands in 1967 and the Cuyahoga River had become so polluted it caught fire for the second time in 1969.

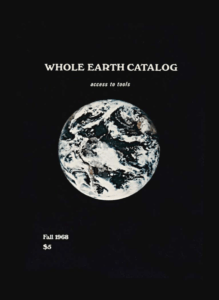

You’d think at least one of the time travelers might have mentioned that at least amongst themselves. The Whole Earth Catalog with its emphasis on ecology and self sufficiency had already gone main stream in 1968 in answer to the already well established hippy “back to the earth” movement. Yet not a word was spoken.

A twice spontaneously combusting river should have brought entire flocks of canaries to their deaths in the metaphorical coal mine, but it didn’t. “Litter” and “pollution” were still the two most damning words of the day. Global warming, acid rain and greenhouse effect were whispered in the distance, but the term climate change had yet to enter the popular lexicon.

But science knew. Science had known for half a century what was headed our way. Though just as the link between cigarettes and deadly cancer was known decades prior to overt warnings, the “good science” was hushed and “bad science” (tobacco and oil spent billions lying about their consequences ) was promoted by the powers of capitalism and runaway consumerism to keep us acquiring, not conserving.

So now we are faced not just with worst case scenarios mapped out half a century ago, but with unknown scenarios tinged with horror film like possibilities so terrifying they make you want to board a train or plane to Switzerland and beg to be put down.

The permafrost is melting, yielding up viruses and bacteria long thought to have been wiped out. A young boy in Siberia died of anthrax, its deadly spores carried on the wind from a thawed reindeer carcass long ago infected. Vast quantities of melting ice are threatening to erase coastal cities long before it was predicted to happen. The truth is that no one really knows anymore what the future holds.

No wonder so many of us are panicked and paralyzed. What can any one of us do to effect the vast and immediate changes required to meet the rapidly approaching catastrophe? What can one person do in the fight against fossil fuels? Not much it would seem. And yet, what is the alternative? Do we just collapse like fainting goats pursued by a pack of half starved wolves? “If you’re not part of the solution,” the saying goes, “you’re part of the problem.”

Cognitive Dissonance

So how does one, become part of the solution? For me, the first step was confronting my own cognitive dissonance.

Cognitive dissonance is a term we hear a lot of these days, but what does it actually mean? It’s the feeling that ensues when one’s actions are in direct opposition to one’s firmly held beliefs. That’s the simple definition, but those feelings are not always so easy to define. They can be hidden behind elaborate defense mechanisms designed to protect us from discomfort.

Eight years ago I decided “overnight” to attempt life as a vegan. But in fact, “overnight” consisted of more than half a century of living with cognitive dissonance.

I was thirteen when my best friend, my horse Dandy, was stabled in the barn about a thirty second walk down the driveway from my front door. He was my biggest source of comfort in what was often a turbulent childhood. I could escape for entire summer days on his willing back deep into the wild Connecticut woods, past the ruins of an 18th Century village to a clear, rushing brook whose water I could both drink and swim in with impunity.

Following yet another explosive confrontation with my volatile, war damaged father I could escape to the barn and curl up in Dandy’s manger, fall asleep with his nuzzles and nickers on my neck. And yet, prior to escaping to the barn my chore was to feed the family dog. Down into the cupboard I reached to extract a can of Hill’s Horse Meat. The words “horse meat” were not obscured by tiny print at the bottom of the back of the label but writ large, proudly even, in big blue letters against a white background. As I turned the handle of the can opener, piercing the tin top, the fragrance of horse meat wafted up my nostrils. I thought it smelled delicious. I emptied the contents into the dog’s dish, rinsed out the can, tossed it away then ran to the comfort of the barn.

Would I have sat down to eat a horse meat steak at that point in my life? Hell no. But I ate steak and burgers with three pet cows in the back yard, the cows so tame, affectionate and forgiving we could ride them, so intelligent they knew how to enter the house when we weren’t at home and devour the contents of the bread drawer.

The once living creature on my plate had died and lived a miserable existence so I could eat it. I didn’t think about it, I felt it. The life and death of that chicken entered me. There was no difference between us. We were the same.

By the time I made my overnight vegan decision I was living for a year in Normandy, cheese capitol of France, and even though I had long before given up veal, lamb, beef and pork I was still eating chicken in spite of a disturbing observation: A chicken’s chilled, white carcass sitting up in a roasting pan very much resembles from behind a living human infant. On one evening as I pierced perfectly crackled roasted skin releasing mingled perfumes of garlic, rosemary and lemon, then severed the thigh from the breast the truth I had been hiding from rose unexpectedly; cognitive dissonance exploded. The once living creature on my plate had died and lived a miserable existence so I could eat it. I didn’t think about it, I felt it. The life and death of that chicken entered me. There was no difference between us. We were the same. And it wasn’t just the chicken, but all animals. I looked back at myself turning that can opener and enjoying the fragrance of horsemeat and the revulsion and horror I felt were overwhelming. I was stunned by my own blindness.

***********

The interesting thing about confronting that particular cognitive dissonance (we all have many) was that my armor was pierced by an acute beam of light. What else was I hiding from? When was I sleepwalking as I went about my days? Giving up meat and dairy brought my attention to my leather shoes and bags, to my choices of skin care products and cosmetics, to soap, both laundry and personal, to cleaning products and on and on. Now it wasn’t just a piercing beam of light. The windows were thrown open wide and the sun poured in lighting up the darkest corners of my daily life and I began to devour information like a famished woman at an all you can eat buffet.

Darn It

Outlander taught me about taking care of the clothing I own. I’m passionate about the costumes on the show and pay close attention as I watch and rewatch episodes. I began to notice that what often seemed like a whole new costume were actually bits and pieces of other costumes. Petticoats became linings for a hand me down cloak; a ruined woolen skirt became trim for another outfit. In Season IV Jamie is still wearing his father’s leather coat and he has a blue jacket that sports visible darning on one shoulder. Darning! Who darns anymore? Most everyone throws clothes with holes in the bin and buys something new. Thanks to Outlander I am learning to darn and I have discovered that when done well it’s nearly an art form. It doesn’t shriek “I’m too poor to buy something new” but instead announces that a garment is loved and cared for.

What Can I Live Without?

It was also Outlander that prodded me to ask: What am I living with now that I could live without? Several times the production company Starz has asked its Twitter followers what they would take with them if they traveled back two hundred years. The sensible ones (and I count myself among them) answered: Antibiotics. But most answers concerned electricity, indoor plumbing, heating systems, air conditioning, cell phones, TV, computers, Spotify (!) and WiFi. A lot of women said underwear, revealing a dearth of knowledge about the reality of wearing 18th Century clothing. One woman answered red lipstick which made me laugh. Yeah, I might bring red lipstick. Women were also justifiably concerned with menstrual hygiene.

But shocking to me were the cell phone, WiFI, electricity and air conditioning answers. The first two have been forced upon us by technology that has nearly wiped out other forms of communication. Few people have landlines anymore and although writing a letter is still possible, the time and effort involved including the trip to the post office and the cost of a stamp promotes sighs of exhaustion and ennui rather than inspiration and creativity.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“Climate Change: The Short Docu Series”

![]()

“Activist Films and Literature: Do They Inspire Action?”

As for air conditioning, I have lived most of my life without it. Hot, humid New England summer nights were relieved with open windows and glassfuls of ice to crunch. Daytime heat was relieved with swims in icy spring fed ponds and brooks. In the seventeen years that I’ve lived in Italy I’ve had no air conditioning and only in the last two have I had the luxury of a fan.

Electricity? It would be madness to consider living without it, right? What happens during a hurricane or blizzard with the power goes out? Yet I have lived happily without it by choice for lengthy periods of time. Same with indoor plumbing, including a winter in Maine when the temperatures dipped to minus 30 and even lower. I admit that going outside to the privy at night was unpleasant, but it wasn’t bad enough to induce despair. I lived in a boat house for six months with only a solar shower — a marvel of engineering consisting of a plastic bag full of water with an attached hose. The summer in question consisted mostly of fog, chilly temperatures and plagues of thunderstorms so it was easier to stay clean by diving into the ocean then brushing off the dried salt with a loofah sponge. But I would relive those six months with gratitude.

I’m not advocating living permanently without electricity or running water, but the truth is that with minimum effort one can adapt to almost anything. We don’t really need all that we think we do. When your day consists of simple tasks to survive, life slows down, small wonders become apparent, the minute winning days wrap themselves around you and you find that you are not merely surviving, but thriving. Something inside you becomes unleashed, a creative energy, a sense of peace. A distraction could be something as small as two orange butterflies chasing each other in circles or startling like the crash of a large wave hitting the shore, the image of a terracotta sail on a sloop passing across a still bay framed above and below with brilliant blue; the rumbling crack of water freezing in a lake or pond in the dead of winter, a swirl of snow from the pine tree shaking off her coat outside the window. When life slows down to such an extent something preternatural in us says, Yes, this is the way it’s supposed to be.

How Do We Get Back to That Amidst the Clang, Clamor and Constant Claim on Our Attention in the Madness of the First Quarter of This New Century?

I have begun asking myself, “What do I miss?” The hum of bees and the dance of butterflies are missing in the beauty of my Tuscan landscape crowded as it is with olives and grapes so I have begun planting masses of lavender knowing that they will come. My first summer here there was one lonely bat; now even he is gone. Why? Not enough insects to eat. I make a note to ask my landlord, proprietor of vast swaths of land going back to the time of Machiavelli, just what it is that is sprayed every Spring on the olive trees that dot the hills for miles. My surroundings may look like the background in the Mona Lisa, but “good living through chemistry” hides stealthily within this Renaissance painting. In the summer the house martins and swallows swoop and dive overhead, their nests hidden in the nooks and crannies of this 13th Century building, but there are no songbirds. That they have all been eaten by Italian hunters is a myth, my local vegetable vendor tells me. The reason is pesticides. “It’s getting better,” he tells me, “but not by much.”

I’ve begun asking around to nurseries, farmers, shop owners and mostly old people, “What gives?” What is happening now that wasn’t happening when you were young? What isn’t happening now that happened when you were young?

“C’era una volta,” they tell me, “Once upon a time there were almond trees here and every fruit you could imagine: Peaches, apricots, cherries, figs. But that was when there were contadini — farmers. Now it’s only olives and grapes because that’s where the money is.” And where the money is there are chemicals.

Italy is not my country of origin. While the changes I’ve witnessed since living here are staggering I haven’t witnessed the generational changes here that I did in my native New England when, at age six, I was sprayed with DDT by a huge truck as it passed by my home. I saw Bluebirds disappear for decades and at an early age was moved to grief and anger. But until recently I haven’t felt the right to express or even feel my anger with Italy. It seemed, for lack of a better word, impolite. I am, in spite of citizenship based on ancestry, a guest here.

****************

Is It Anger or Is It Grief?

Anger is not a valued emotion in polite society. And if you’re a woman, then God help you because there’s nothing society dislikes more than an angry woman. We are told to shut up, sit down, leave the table, go to our room. In spite of the glory days of Italian film when Sofia Loren swore magnificently at Mastroianni and threatened him with a giant rolling pin, female anger in this still patriarchal society can be viewed as humorous entertainment, but is not something to be applauded in real life. The once celebrated and very angry Orianna Fallacci is dead and no one has come along to take her place.

Cognitive dissonance can arise not only when your actions, but your inaction is in direct conflict with your held beliefs. If I believe climate change is real, driven by humans and is destroying the planet yet can do nothing to combat it even in the smallest way I am left with not just anger but a bitter, inchoate rage and sense of impotence that will eat me up and spit me out into an early grave.

The thing about anger is that most of the time it’s covering up something else even more painful to feel. Fear, for one. Feel intense fear long enough and it will kill you. Anger also covers up profound sadness and grief. It’s one of the early stages of grief coming right on the heels of denial.

If I ask myself, “What am I so angry about?” the underlying, unifying cause is loss. It’s always loss. I am angry about the Sixth Mass Extinction. I don’t want to live in a world with no elephants or giraffes or wildebeasts. I’m angry about millions of people already being displaced by climate change, angry about children dying in Iraq, Syria and Yemen. Angry that there are no songbirds in summer in my corner of the world. I am angry because it’s easier to feel anger than grief. But it’s only when I confront my grief head on that I can use anger as a tool for change even if that change is as small as leaving meat and cheese off of my dinner plate.

In the movie “Julia” we meet the writer Lillian Hellman early on as, in a fit of pique related to her work, she throws her typewriter out of the window. She is one pissed off woman. Later in the film she is asked by her friend, Julia, if she’s still angry. “Yes,” is her immediate and sharp edged answer. “Good,” says Julia, “you’ll need it to do what I’m going to ask you to do.”

What Julia asks Lillian to do is smuggle cash into Germany to help pay for Jews to leave the country. It’s Lillian’s anger inflamed by her sense of injustice that lets her sew money into her hat and sit under it in intense fear as she crosses the border by train into Germany.

In 1963 CBS’s Eric Sevareid interviewed Rachel Carson just prior to her death at age 56. The interview is part of a larger broadcast about pesticides and is just as alarming today as it was when it was made. You wouldn’t think to hear and see her that Ms. Carson, author of Silent Spring, was angry, but you can bet it was something more than profound sorrow that kept her writing and talking in the face of vile pushback. She was called an hysterical woman, an alarmist, “a spinster with an affinity for cats.” Her book was demonized as an emotional outburst. To be sure she had to have felt sorrow as well as alarm when faced with dead birds and fish from pesticides, but sorrow drains us of energy rather than ignites it. It takes anger for that.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c6fAP6Fjx-Y

I have neighbors who mockingly chide me for my sense of outrage about the present planetary conditions. They tell me to “don’t worry, be happy,” and to just ignore the news as there is nothing I can do about it. But such people and their lackadaisical attitudes may be on the wane if the latest mass school exodus and the protests of ExtinctionRebellion against climate change are indicative of anything. It will be the anger and outrage of young people who stand to lose the most that will ultimately demand the attention of the adults in power. It is young people who are becoming vegan, buying their clothing and possessions second hand, standing up, speaking out and shouting down ignorance and apathy. It is young people who will save us if anyone can and to whom we will owe everything.

Watching Outlander with its display of the natural beauty, light, clear rushing water and the flora and fauna of the unspoiled earth is evocative of all that has nourished and sustained me throughout my life.

Sometimes I ask myself what it is I will remember in my last moments and without exception it is always images from nature. An Imperial Lily from my mother’s garden bursts open, touched by the first ray of the rising sun, revealing crystal droplets of nectar; a lightning bolt pierces the flat platinum surface of the sea, leaving behind the sharp scent of ozone; a young doe comes each morning to play with one of my cats, the whistling sound she makes breaks the silence like the blade of a sword drawn swiftly through the air; a 20 month old baby spins joyfully beneath his first experience of falling rain; the red blur of a fox streaks though crepuscular light… All these and more are the memories that come to mind, all this loveliness whose loss is too painful to bear.

What will your memories be and what will you do to ensure that others will share them? That is the essential question facing us all.

Thank God men cannot fly, and lay waste the sky as well as the earth.

— Henry David Thoreau