Editor’s Note: This piece is co-authored by Arriana Spallone and Gaia Garofalo.

Following the Lehman financial debacle in 2008, Iceland experienced a de facto bankruptcy triggered by an economic crisis so profound the country appeared to be doomed to failure. Fast-forward 8 years and, while half of Europe is in turmoil, Iceland has successfully tackled default. An economic miracle – and water may be the answer.

When the Eyjafjallajökull erupted in the spring of 2010 it disrupted life in Europe, reminding us all of the strength of nature in front of which we were powerless. Feeling the risk of being stranded somewhere, we became increasingly intrigued with this mysterious country which had risen to be one of the most powerful international financial centres and where an active volcano was effectively able to hinder the everyday functioning of the world. A paradox that summarizes the fascinating identity of Iceland, both modern and primitive at the same time.

The land of ice and fire is a country of natural wonders, with icy glaciers and raging volcanoes, where the relationship between man and nature is constantly reminded of the strength of the latter. Immediately catching one’s eye, water is the main character of this amazing island, surrounding and replenishing it from the inside.

What makes it all so special is the way the people of Iceland have been able to take advantage of such a resource. Forty years ago the country was classified as a developing country heavily reliant on imported oil and coal. Today its energy system can count on an efficient modernization where the production of electricity and heating is entirely based on a readily available domestic resource: water.

PHOTO CREDIT: NordicVisitor.com

PHOTO CREDIT: NordicVisitor.com

A Nordic European island country located between the Arctic Ocean and the North Atlantic, Iceland is sparsely populated with over 300,000 people living in an area of 103,000 km2. The country is a member of the Schengen area and of the European Economic Area, and, in 2009, it applied to join the European Union.

Although it decided to suspend its application in 2013, the accession of the nation to the EU remains a strong political debate as the drive to benefit from the advantages of a broad free market is juxtaposed to the experience endured during the crisis, where flexible decision-making proved to be crucial.

In the 1990s, Iceland repositioned as a low tax nation attracting foreign investment. A swift transition followed and the country quickly transformed from an export economy to an international financial centre.

The numbers were huge to the point that the assets held by the banking system were worth over 10 times Iceland’s GDP. The great availability of capital gave birth to a number of epic projects that have come to symbolize the magnitude of the financial crisis, such as the Harpa Concert Hall sponsored by Landsbanki and completed with government funds following the events of 2008.

The high speed with which Iceland was able to take centre stage in the world of finance was matched with a high degree of inexperience leading to the three biggest banks, Landsbanki, Glitnir and Kaupthing, to collapse. Following Iceland’s unorthodox decision to let the banks fail, this became the third largest bankruptcy in history.

The decision to recognize the banks as too big to be saved was followed by an implementation of a variety of reforms including strict capital controls and austerity measures. The private sector was heavily penalized and virtually all businesses were cut-off from access to capital and went bankrupt.

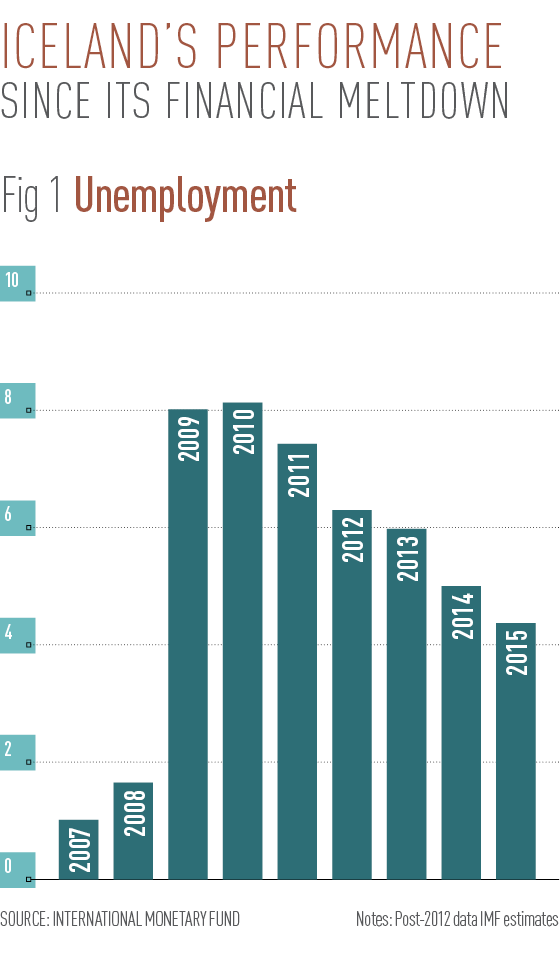

Yet, today Iceland’s unemployment rate has gone down and the country is a top economic performer, with GDP growth of over 4% in 2015.

PHOTO CREDIT: WorldFinance.com

Following the 2008 financial crisis, Iceland received emergency financing from both the International Monetary Fund ($ 2.1 bn) and neighbouring countries ($ 2.5 bn). Clearly distancing itself from the outcome experienced by other indebted countries, Iceland began repayments earlier than expected when in 2012 it was able to return 20% of the IMF loan.

The IMF considers Iceland a success story, recognizing the efficient use of natural resources in three key sectors (energy, traditional fishing industry and tourism) as the means by which the country was able to re-balance itself.

Related article: “WATER POLITICS IN THE MIDDLE EAST“

Yet, it is worth considering that, in a speech at the 2013 meeting of the OECD Ambassadors, the President of Iceland Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson emphasized the rejection of the financial orthodoxies of the Washington Consensus.

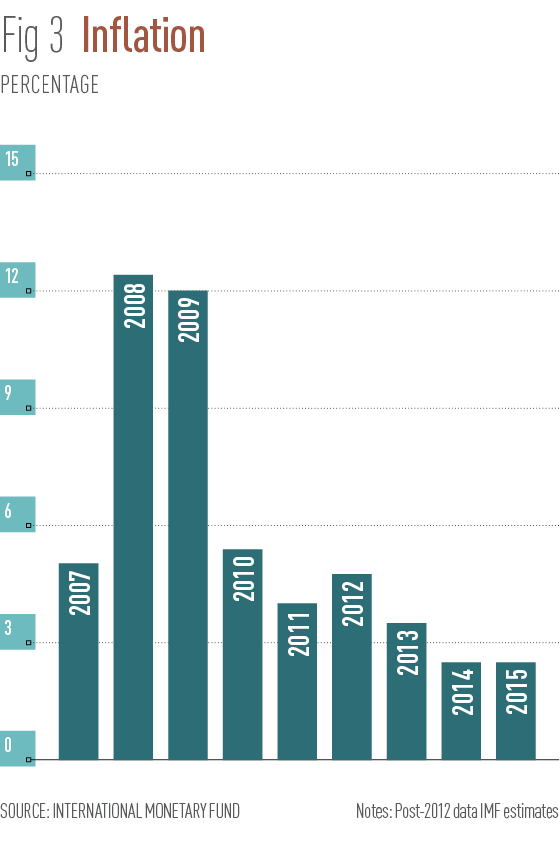

Surely, the single currency (the Icelandic Krona) acted as an advantage as it was promptly devalued by 60%. This meant that while wages did remain stable the country became more competitive. As a result, the efficiency of the clean energy economy process was not hindered.

The productive use of water as a resource gives an answer to why, despite the economic turmoil of the past decade, Iceland has been able to maintain the principles of its welfare society.

![]() Looking at the water-driven clean energy economy, immediate advantages stand out and it is not a case that President Grímsson recognizes it as the main reason behind the strong economy recovery. Not only has long-term access to clean energy proven to be strategical in attracting foreign capital and in enhancing the prestige of Iceland as a country, but it has also allowed for a decrease in expenses. For example, the money saved from importing the heating alone in the last 10 years amounts to 1 year GNP. Reduced spending on heating and electricity both at a macro and household/individual level means an increased availability to invest resources otherwise.

Looking at the water-driven clean energy economy, immediate advantages stand out and it is not a case that President Grímsson recognizes it as the main reason behind the strong economy recovery. Not only has long-term access to clean energy proven to be strategical in attracting foreign capital and in enhancing the prestige of Iceland as a country, but it has also allowed for a decrease in expenses. For example, the money saved from importing the heating alone in the last 10 years amounts to 1 year GNP. Reduced spending on heating and electricity both at a macro and household/individual level means an increased availability to invest resources otherwise.

This has been evident in the country’s recent participation to the Football Euro 2016 as a massive 10% of the population has traveled to France in support of its team. Moreover, Iceland’s recent success in the game is strongly related to the use of geothermal power as heated fields allow outdoor practice all year round.

Notwithstanding the importance of water as a direct resource for energy, it is worth noting that Iceland has also been able to tackle the crisis by reinforcing other sectors.

Water and water related energy has proven useful in boosting the traditional fishery industry (for example, geothermal heat has been applied to fish farming ultimately resulting in the Reykjanes geothermal power park Senegal sole farm) and tourism, a sector that has grown by 100% from 2006.

The Blue Lagoon, named by National Geographic one of the 25 wonders of the world, is emblematic of how the clean energy economy can provide an opportunity for tourism. A water reservoir created by a power plant spill, it can count on a base of more than 300,000 tourists per year, an astonishing number if you think that it equals that of the total population of Iceland. Finally, water is also key in determining the everyday life of the local population, by bringing people together especially as communal pools are thoroughly present in the territory. Born out of necessity (in the past, though fishing was at the base of the economy, the majority of the population did not know how to swim, resulting in many life losses), today they offer a huge tourist attraction while providing a key explanation to the country’s happiness index.

Iceland today is a success story – in the past forty years the country underwent a variety of transformations: from a developing country to a growing export economy, an international financial centre and finally a top economic performer, using water as a way to conquer the world stage. Iceland’s determination in rendering itself independent from coal and oil imports by efficiently developing a clean energy economy based on domestic resources has proven successful.

Today the country has been able to achieve full energetic independence via renewable energies – and water has played a vital role in this.

For a full mindmap behind this article with articles, videos, and documents see #water

PHOTO CREDIT: Britannica.com

PHOTO CREDIT: Britannica.com

How Water Works for Iceland

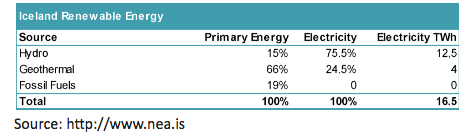

Iceland is the only country in the world that can claim to obtain 100% of its electricity and heat from renewable sources, thanks to the development of geothermal and hydric resources.

Compared to other European countries, this result is outstanding: the European Renewables Directive sets the goal at 20% in 2020, but many countries are still distant from the achievement. To give some examples, Germany produces 13% of its gross final energy consumption; Italy stops at 17% ;France at 14% and the United Kingdom at 7%. Today Iceland generates 100% of its electricity thanks to renewable energy: 75% of that from hydro, and 25% from geothermal.

Equally significant, Iceland provides 87% of its demand for hot water and heat with geothermal energy, primarily through an extensive district heating system. Altogether, hydro and geothermal sources meet 81% of Iceland’s primary energy requirements for electricity, heat, and transportation.

This is a record in the modern era.

The utilization of energy from geothermal wells releases greenhouse gases trapped in the earth core such as carbon dioxide, hydrogen sulphide, methane, and ammonia. These emissions are lower than those associated with the use of fossil fuels for which the adoption of geothermal energy sources is considered to have the potential to mitigate global warming and have a favourable impact on the environment.

While the environmental effect of geothermal energy generation may be favourable if compared to other sources of energy generation, however it is not insignificant and can cause substantial environmental and human health deleterious effects. Nonetheless, lucky Iceland is unique in this aspect as well, as the gas content of low-temperature water is in many cases minute, as in Reykjavik, where the CO2 content is lower than that of the cold groundwater.

Looking at the phenomenon from an economic perspective, it is undoubtedly cost efficient: the price for consumption of geothermal energy is in the range of one to three cents per Kwh, less than half the price compared to the cost of heating via electricity (eight cents) and one-quarter of the price compared to the cost of heating using gas.

Therefore, it is safe to say that Iceland not only achieves outstanding results in terms of ecological impact, but also in terms of cost efficiency.

Why is Iceland so virtuous, and why does it succeed where many countries fail worldwide?

Undoubtedly, its unique geological conditions and its isolation play an important role. Iceland is exquisitely positioned on the Atlantic ocean ridge, with part of the ocean ridge that runs straight through the country from south-west to north-east forming a sequence of active Volcanoes and geothermal zones where endogenous fluids that may reach temperatures of circa 200 ° C one km below the ground flourish.

Many of these fluids, found at an average temperature of circa 100°C are directly utilized to warm buildings, swimming pools, thermal stations, greenhouses and for aquaculture. In some cases, the geothermic source is close enough to the chain of distribution; in other cases, nonetheless, Iceland has proved it possible to transmit hot water across long distances.

Reykjavik has in fact the largest system of geothermal district heating on earth, ahead of some of the most advanced cities in China. A small country like Iceland is a leader in geothermal development and also exports its technical expertise worldwide. The country, along with the Philippines and El Salvador, is among countries with the highest penetration of geothermal energy in electricity generation.

On a per capita basis, Iceland is an order of magnitude ahead of any other nation in installed geothermal generating capacity. This means that Iceland not only manages to totally sustain itself, but helps provide energy to countries throughout the world, and does so successfully.

It should not surprise that Iceland’s third-largest bank, Glitnir, helped finance the world’s biggest geothermal district heating project in the city of Xianyang, China, and that it retains a staff of geologists to evaluate the potential of early stage drilling projects.

Going back in history, Iceland’s tie to renewable Energy is once again closely linked to an economic crisis, as the real boost in the use of renewable energy arrived in 1973 with the first global oil crisis: the significant increase in the price for oil led Iceland to boost the extraction and transmission of geothermal and hybrid energy especially for heating that in Iceland must be guaranteed all year long (even during August temperatures rarely rise above 10 ° C).

It is in the 70’s that the first important geothermal plant was established. Today, electricity is produced into six different power plants for a total of 664 MWe installed and an annual production of 6 TWh.

Therefore, the rising cost of oil and environmental issues rapidly convinced the government – in the early 70’s – to make the decision of eliminating the use of fossil fuels for heating as soon as possible. Large amounts of economic resources were destined for research in the field of renewable energy and for training, together with a fund for the mitigation of risk due to geothermic perforations.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Andreas Tille

Looking to the Future: Supercritical Steam

Not content to max out the country’s geothermal potential using existing technologies, a consortium known as the Iceland Deep Drilling Project (IDDP), which includes the Icelandic government, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the European Union and Alcoa have banded together to tap an exotic and hard to exploit form of geothermal energy: supercritical steam.

When steam exceeds a certain temperature and pressure—in excess of 400 degrees C and 250 times greater than normal atmospheric pressure—the density of steam becomes identical to that of liquid water.

Supercritical steam has already been used in coal-fired and nuclear power plants. The mechanism by which it yields higher efficiency is complicated, but ultimately it boils down to this: steam turbines need very hot steam in order to produce power, and supercritical steam is much closer to this temperature than cooler steam. As a result, very little energy is wasted in transferring heat from the steam that comes out of the ground to the steam that will spin the turbine.

In addition, the entire system can be constructed under the assumption that steam and water don’t have to be separated in the early phases of the power generating cycle—because at these temperatures and pressures, these usually distinct phases of water are literally one and the same.

This is an ambitious project for Iceland, as tapping supercritical steam will require drilling deeper than any geothermal project has ever drilled before; as deep as five kilometers below the surface. Dissolved solids, toxic metals, and corrosive gases are only some of the obstacles the IDDP will have to overcome in the next 10 years—but it is a process that Iceland is proud to lead.

Because of its singular geological position, Iceland has the special conditions needed to generate geothermal energy. The high degree of volcanism, along with the world-renowned expertise of Icelandic specialists in the field of geothermal energy utilization, enables Iceland to be the world leader in the production of this eco-friendly, sustainable and renewable power.

Moreover, nowhere else other than the Great Rift Valley in Africa, is seafloor spreading visible on land; this constant generation of new crust makes the country one of the most geologically active on Earth. And it is that activity the Icelanders are intelligently tapping in order to boost their economy, maintain environmental sustainability and preserve its position as the first exporter of geothermal expertise worldwide.

Recommended reading: “IMPAKTER ESSAY: WATER, WATER EVERYWHERE, NOWHERE AND SUCH HIGH PRICES“