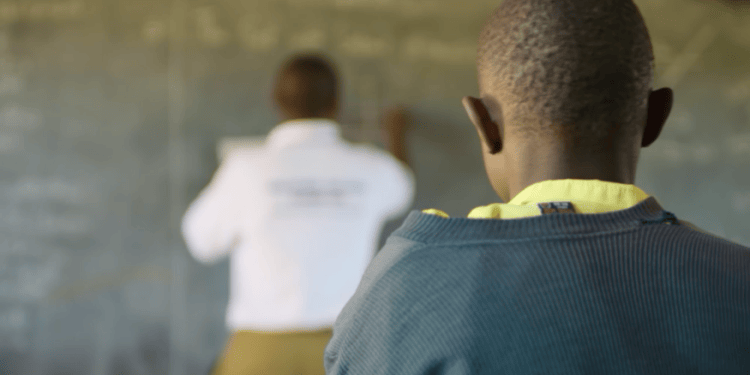

His teachers said he was lazy and didn’t pay attention. His clothes were falling apart and never clean, he didn’t socialise with the other children. A positive future for Brian was hard to see. It turns out it was hard for Brian to see, but nobody knew it, including Brian himself.

When you grow up with poor sight you have no relative experience of clear sight to measure it against, and therefore cannot see what you cannot see.

This was the case with Brian, a twelve-year-old living in rural Kenya. When a vision screener visited Brian’s school and found his vision to be really poor, his teachers were shocked. What is more shocking is that one in three people on the planet, 2.5 Billion people, can not see as clearly as they could. Most of these people would achieve their visual potential with a simple pair of spectacles, a solution to poor vision that has been around for over 700 years.

Related Article: “HEALTH IN THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS“

Poor vision is not simply a “health” issue: it is a social issue; an educational issue; a productivity issue; a gender issue and ultimately an issue of individuals and communities realising their full potential.

Not seeing clearly, results in reduced social interaction. The subtle cues of communication: a look, a smile, body language, all can be missed when your world is not in focus resulting in social isolation. Not seeing clearly at any age can impede the ability to learn, especially in formative years of childhood. This has a consequential lifetime effect of limiting education – the process of facilitating learning and the acquisition of knowledge, skills, values, beliefs and habits. Reduced social and educational opportunity drastically reduces productivity. The ability to become independent and contribute to family, community and society is impaired and alongside the social impact this has, there is a dramatic negative economic consequence. Figures suggest up to 3 Trillion dollars per year are lost globally due to avoidable vision loss. For all these consequences that limit Brian’s future, there are two girls facing the same limitations. Gender inequality is fuelled by a lack of the fundamental right to sight.

Photo Credit: Rolex / Joan Bardeletti

Almost one third of the world today are school children or infants. The epidemic of myopia (short-sightedness) is reaching staggering levels with some countries suffering from over 90 percent of school children graduating from secondary school with myopia. Combined with population growth, these problems are amplified and will continue to grow at an alarming rate unless we take action now.

Poor vision is not simply a “health” issue: it is a social issue; an educational issue; a productivity issue; a gender issue and ultimately an issue of individuals and communities realising their full potential.

After Brian was found to have poor sight, a letter was put in his bag to take home for his parents, explaining he needed to be examined by a specialist. Sadly, Brian, like many children living in poverty, lost his parents in infancy. His grandmother is his sole carer and it turns out she has been blind for many years.

In many ways, Brian was lucky. It is common in low and middle-income countries for children not to go to school at all if they have a parent or grandparent who cannot see. The elderly relative becomes dependent on youthful, seeing eyes to support them in daily activities. This leads to children missing school and much of their childhood.

Brian’s grandmother’s biggest fear is that she might accidentally poison Brian, as she cannot see what crops she is picking and cooking to feed him. She only has a distant memory of Brian’s infant face and has become isolated to the four walls of her tradition clay home, afraid to walk in the dark that has become her world, day or night. Brian’s grandmother is blind from cataract. An age related change in the lens of the eye for which cost-effective curative treatments exist and are available in almost every country in the world. Despite this she has been blind unnecessarily for a decade. Around 20 million people worldwide are cataract blind, and many more who are not yet blind from cataract are visually impaired. The surgical removal of the cataractous lens and replacement with an artificial plastic lens has been perfected over many decades, and can now be performed in ten minutes for ten dollars. Of all the causes of blindness, 80 percent are avoidable, either curable (cataract, refractive errors) or preventable (diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, trachoma, river blindness).

Then why do so many people remain blind?

The barriers that prevent access to eye care services follow:

- Awareness – On both a policy and individual level, there is a lack of awareness that curative or preventative treatments exist and are available.

- Bad Services – High pressures on services can often lead to a poor reputation. Even when an alternative is available or services improve, poor reputation remains a barrier.

- Cost – Direct (cost of treatment, insurance) and indirect costs (travel, time away from home) are often prohibitive to receiving treatment in low-income communities

- Distance – The travel logistics and time required to reach a treatment facility are often too great to enable access to those most in need of services.

- Escort – Provision for a carer who will escort a person with sight-impairment is often overlooked, for example, there is no space on the outreach bus or hospital accommodation for the escort.

- Fear – A lack of effective counselling and investment in education leads to many potential beneficiaries holding beliefs that leave them fearful of the treatment they will receive.

- Gender – All of the above barriers affect women and girls more than men and boys.

Vision and the Sustainable Development Goals

Vision can be specifically linked to Goals 1No Poverty; 3 Good Health and Well-Being; 4 Quality Education; 5 Gender Equality and 8 Decent Jobs and Economic Growth. It is most frequently categorised as an “eye health” issue and therefore linked to Goal 3, for which Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is core.

As cataract surgery is one of the most frequently performed elective surgical procedure in the world, it forms a very strong indicator of UHC. Methodologies for population level data on Cataract Surgical Coverage (CSC) are well utilised globally, such as the Rapid Assessment of Avoidable Blindness (RAAB), which has been used in over 70 countries to date. RAAB is also able to provide valuable data on quality of services as well as equity of service provision (gender, age, urban/rural) with new features including the prioritisation of reviewing socioeconomic status for increased inclusion.

Photo Credit: Rolex / Joan Bardeletti

Due to the attribution of vision to health and the availability of high-quality data, vision is often limited exclusively to health budgets despite it’s cross-cutting impact on individuals, communities and society. Historically it has had to compete for attention against immediate and life threatening “health” concerns, usually disease specific campaigns (HIV/AIDS, Malaria, Ebola, etc.) resulting in low awareness, low prioritisation and ultimately a world with low vision.

As described in Brian and his grandmother’s story, vision has implications beyond health, including: social wellbeing, education, productivity and gender. The SDGs recognise three cross-cutting themes: Women and gender equality; SDG-driven investment; and, Education for sustainable development. These three themes are crucial to the realisation of the SDGs and vision is fundamental to the feasibility of achieving these goals.

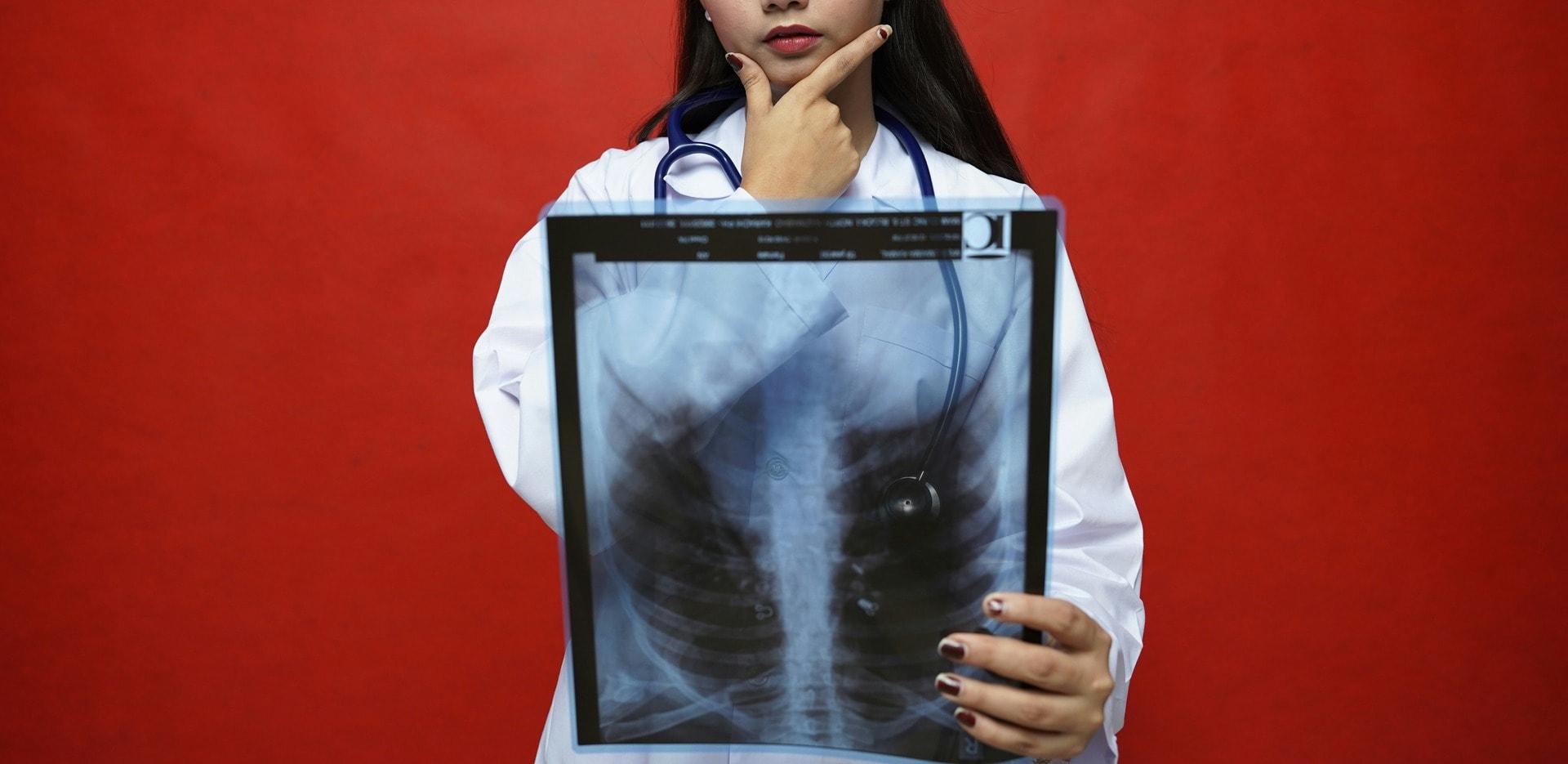

Photo Credit: Rolex / Joan Bardeletti

The ambitious set of goals are to be commended, however, the value of momentum and shorter-term attainment of progress should not be overlooked. The cost-effective, existing measures for life-changing impact to be made through the provision of vision solutions could create the much needed positivity and momentum that can create a wide scale change. Reducing the barriers to access of eye care services lays down the foundations to provide access to a wider range of services, including other health provision.

An individual who realises their visual potential stands to gain the knowledge, skills and life experience offered through education, that will equip them to live a rich life and serve their families, communities and society. For those in adulthood living with unnecessary sight-loss, the restoration of vision leads to the restoration of dignity and independence. The sector is uniting to deliver comprehensive vision services across the world. In the same way we all work to reduce barriers for individual potential beneficiaries, like Brian and his grandmother, now is the time, for our generation to reduce the barriers that prevent providers from serving those who are silently waiting.

Sometimes it falls upon a generation to be great, you can be that generation

– Nelson Mandela

In the Photo: Brian and his grandmother the day they saw each other’s faces for the first time in ten years. Photo Credit: Peek

Our mission is to strengthen health systems and empower individuals by creating tools and health intelligence that radically increase access to eye care worldwide.