For the first time in history, a major oil company, Royal Dutch Shell, has been ordered by a court in The Hague – the country where Shell is headquartered – to follow the Paris Climate Agreement and cut its carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 compared to 2019 levels. This is a landmark decision that is destined to reverberate beyond the Netherlands: Now, no oil company anywhere is safe from a similar court injunction.

It has taken a long time to get to this watershed moment in the fight against climate change, three years to be precise. It all began in 2018, when several climate activist movements got together to build a case against Shell: Fossielvrij NL (the Dutch sister organization to 350.org), Milieudefensie (the Dutch sister of Friends of the Earth) and four other climate organizations, the six of them drawing together a further 17,000 Dutch citizens that joined in the lawsuit as co-plaintiffs.

The court victory, the first of its kind, is sweet for climate activists around the world. Cox, the lawyer for Milieudefensie said: “This is a turning point in history. This case is unique because it is the first time a judge has ordered a large polluting corporation to comply with the Paris climate agreement. This ruling may also have major consequences for other big polluters.” In fact, he called on activist organizations around the world to “pick up the gauntlet,” and take legal action to force multinationals – and not only oil firms – to play their full part in tackling the climate emergency.

Bas Eickhout, a Green Member of the European parliament’s environment committee, said: “This ruling is really good news for the climate. It increases the pressure on large polluters and helps us in Europe to tighten climate policy for them as well. They can no longer escape the climate crisis: the international climate targets must also apply to them.”

So are court rulings going to be a major line of action to defend the planet from depredation by big corporations? It would seem that, even if the legal road is time-consuming and taxes people’s patience, it gives results – even if Shell has decided to appeal the judgment. But the appeal is likely to take two years and, as Cox pointed out, one can hope that Shell managers and stockholders would act in the meantime and begin to seriously apply the ruling.

Because, as is to be expected, in the courtroom, Shell defended its case, arguing that it does have a conservationist approach, claiming to be a “green” company. In February this year, it announced it would accelerate the transition of its business to net-zero emissions, including targets to reduce the carbon intensity of energy products by 6-8% by 2023, 20% by 2030, 45% by 2035 and 100% by 2050.

But the case against Shell was clear. Lawyers for the plaintiffs argued that Shell had knowingly broken article 6:162 of the Dutch civil code and violated articles 2 and 8 of the European convention on human rights – the right to life and the right to family life – by causing a danger to others when alternative action was possible. Shell, they convincingly claimed, had known for decades of the dangerous consequences of greenhouse gas emissions and its announced targets were insufficient.

The court agreed. It said that the “emissions reduction targets for 2030 are lacking completely” and while the company had not acted unlawfully, it established that there would be an “imminent violation of the reduction obligation.” Such obligations, it noted, did exist under both Dutch law and the European convention and that the company had known for “a long time” about the damage of carbon emissions, concluding that “policy intentions and ambitions for the Shell group largely amount to rather intangible, undefined and non-binding plans for the long-term.”

Shell argued that there was no legal basis for the case because governments alone are responsible for meeting Paris Climate Agreement targets. The court found otherwise, stating that “since 2012 there has been broad international consensus about the need for non-state action, because states cannot tackle the climate issue on their own.” (highlight added).

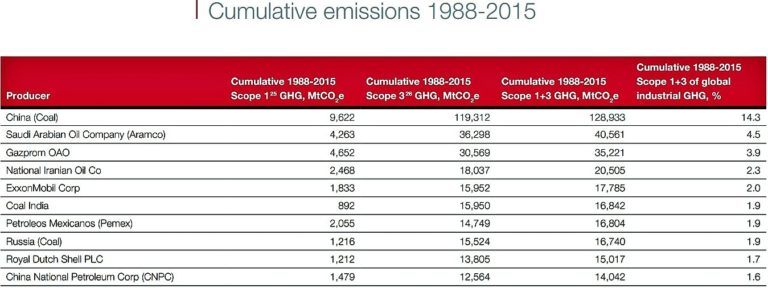

Shell in fact has played a key role in the unfolding climate emergency, as the ninth biggest polluter in the world in the 1988-2015 period, according to the Carbon Majors database (2017 Report):

While Shell’s activities and products are already responsible for about 1% of global emissions every year, the company is investing billions more in oil and gas, the court heard.

It’s not the first time Shell has encountered lawsuits. Notably, earlier this year, on January 29, the news came out that a Dutch court of appeal had found Shell liable for the infamous Niger Delta spills and condemned the company to pay compensation to four Nigerian farmers over oil pollution in the Niger Delta.

The judgment came after an extremely long-running civil case (18 years). The court added that the parent company Royal Dutch Shell was also ordered to install detection equipment that could prevent future damage on the Oruma pipeline, the site of a significant number of the spills.

Nigeria’s environmental degradation caused by oil spills is not yet resolved – and will likely take years to mop up while there’s a real risk of recontamination. But with the latest court ruling against Shell, analysts, according to Reuters, have come to the conclusion that it will result in “Shell’s shrinking.” The 45% reduction Shell is required to commit to would mean, according to Credit Suisse, a 45% drop in oil sales, a decline in natural gas sales and a much larger increase in carbon offsets such as forestation and carbon capture and storage technologies.

This implies a shrinking of the size of Shell’s business to around 18.8 exajoules (ej) of energy output, down from 21.3 ej today, roughly a 12% decline. If that’s the case, then such court rulings really do hurt the bottom line and big corporations are likely to sit up and register the fact.

Shell is quick to defend itself. A Shell spokesperson said: “We are investing billions of dollars in low-carbon energy, including electric vehicle charging, hydrogen, renewables and biofuels. We want to grow demand for these products and scale up our new energy businesses even more quickly. We will continue to focus on these efforts and fully expect to appeal today’s disappointing court decision.”

Shell’s CEO claims more than 50% of the company’s business will come from clean energy in “the next decade,” but says they won’t set a specific target for cutting oil and gas production. #AxiosOnHBO pic.twitter.com/qkW0XSaZQA

— Axios (@axios) May 9, 2021

Actually, if Shell really did what it says it would do, then it would no longer be an oil firm but a clean energy firm. A huge shift. And a very commendable one. But can it manage to become a totally different company?

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Oil spill at Goi Creek, Nigeria, August 2010. Featured Photo Credit: Friends of the Earth Netherlands/Flickr