July 16, in a stormy session, the European Parliament confirmed Ursula von der Leyen’s nomination to succeed Jean-Claude Juncker at the head of the European Commission. Here is our sister publication Impakter Italia’s insightful account of how she got there and the challenges she will now face.

The baptism was no dream for Ursula von der Leyen, the former German Defense Minister. Of course, there is satisfaction for the election to the presidency of the European Commission. Until a few days ago, given the changing mood of many MEPs, it was far from being taken for granted.

The result came with a narrow margin: 9 votes (383 of the 374 needed), which meant that she was handed a demanding mandate, more difficult than expected. A member of German Christian Democrats, she thus won the appointment thanks to the support of [unexpected outsiders] like the Italian 5 Star Movement that had joined the European Parliament mixed group [Translator’s note: the group of politically unattached MEPs]. Moreover, tallying up the accounts, it appears that about 70 votes went missing from the hypothetical majority that should have been available to her.

A complex mandate, therefore, but fundamental for the very survival of the European Union. She is called to face decisive challenges with the “sovereign” thorn in her side. The lack of support for the candidacy of the former German Defense Minister is a clear signal: the nationalist parties on the right will continue their demands, trying to weaken the action of the next Commission.

On the other hand, the new president has shown that she wants to keep the so-called “sanitary cordon” around parties like Salvini’s Lega, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National, and Alternative für Deutschland.

The main issues to be addressed are undoubtedly the environment, immigration, social and economic policies to guarantee the stability of Europe and the containment of nationalism, as suggested by von der Leyen herself. To give an example, in the coming months she will be called upon to assess the Italian debt situation, on which the cloud of the infringement for excessive debt hovers.

The challenge of sustainability

The result of the European elections delivered a much greener European Parliament than expected. Thus the climate emergency ended at the top of the EU’s political agenda. Von der Leyen understood the lesson and in her inauguration speech she highlighted this, also because of her electoral needs (she needed the “support of the Greens”).

The promise was to make the continent free of CO2 by 2050, reiterating that it is not even enough to cut emissions by 40% by 2030. To achieve the ambitious goal she is willing to put on the table a thousand billion investments through the European Investment Bank (EIB).

In the video: Ursula von der Leyen’s bid for Parliamentary support, delivered on the morning of the vote (held at 6 pm on 16 July). It was a statement to MEPs outlining her priorities as Commission President (33 minutes). She opens in French (with a reference to Simone Weil), goes on in German and in the fourth minute moves into English, with a conclusion in German.

The inaugural speech outlined a very green Europe. A continent at the forefront of environmental and climate issues compared to the Chinese and US giants.

A sustainable Europe, in short.

Stringent accounts and immigration

As a former minister of the Merkel government and a prominent member of the CDU, von der Leyen certainly cannot be described as being inclined to give discounts to countries in debt. Above all, of course, there is Italy, already back from a tight negotiation with Brussels. On social policies she made a big promise: She called for a European minimum wage to guarantee rights to all workers and to combat exploitation.

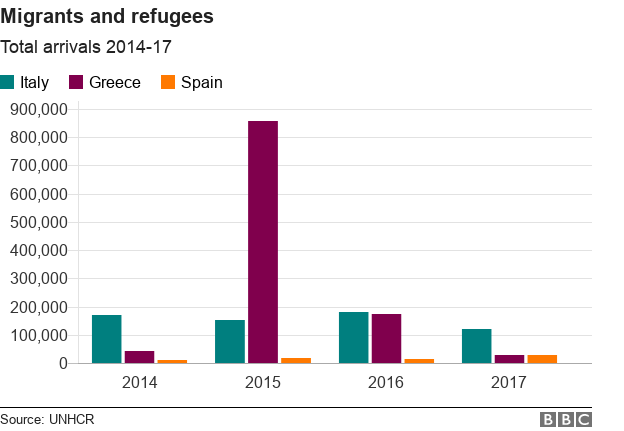

A very delicate subject is certainly that of immigration: the absence of adequate European Union policies has fostered a feeling of fear in the citizens who, as in the Italian case, have taken very critical positions towards Brussels.

From the outset, she has promised to want to reform the Dublin Treaty according to which a migrant must request refuge in the country of first arrival. The task of Ursula von der Leyen promises to be very hard: The position of the Visegrad Group (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary) is very rigid. And rejects any possibility of confrontation and reception of migrants.

Intransigence generates paralysis, threatening to undermine the Union itself. The real political success of the new Commission will most likely be played on this level.

What von der Leyen will do

In short, her programmatic objectives are rather ambitious. For the former German minister, this is going to be a very tough assignment. But what can she really do?

On the environment and the climate emergency, von der Leyen starts with an advantage: Sensitivity to the issue has grown enormously compared to the past and national governments are beginning to understand the possibilities of development brought by the conversion to clean and green energy. In a sense, although the challenge is gigantic, it is the most feasible, also thanks to the large “green” representation in the European Parliament.

The chapter on public accounts is more complex and in any case a relaxation of control is unimaginable. Expect a more malleable rigor on the line of [her mentor] Angela Merkel compared to the North European leaders or to the Dutch premier Mark Rutte who are very strict on the subject.

In this sense, a continuity with the line held by her predecessor Jean-Claude Juncker is foreseeable: Attention to the constraints, but also a willingness to confront the interlocutors.

Unlike Juncker, however, no one will be able to attack von der Leyen for governing a tax haven, like Luxembourg, in the heart of Europe. A factor that is not just secondary and adds to her public image and credibility.

Finally, of the three macro-themes, that of immigration is the true mission impossible for her. The Visegrad blockade is ready to build barricades, as it has always done, to crush in the bud any attempt at real reform of the Dublin Treaty.

The calls for “solidarity” so far have had little effect. It is impossible for von der Leyen’s words alone to cause change. In this perspective, great diplomacy will be needed, trying to involve the countries most open to confrontation. Also because, once again, Italy will have a strategic role: The large number of Salvini’s Lega MEPs, a “ League patrol” in the European Parliament, is ready to act as agent for the Italian government. Ready to do battle against Brussels.