The United Nations’ Predictions of War, Disaster and Famine till May 2015: The IASC Early Warning Map

One always thinks of the United Nations as the harbinger of bad news, in particular dire predictions of global warming as the upcoming “Paris Climat”, the next World Climate Change Conference to be held in Paris in December 2015, is gathering steam.

But what is not so well known is that the United Nations plays a major role in the international community in predicting the next emergencies, man-made disasters like war devastation and economic collapse, but also some natural disasters that can be foreseen, like famine caused by a protracted, on-going drought.

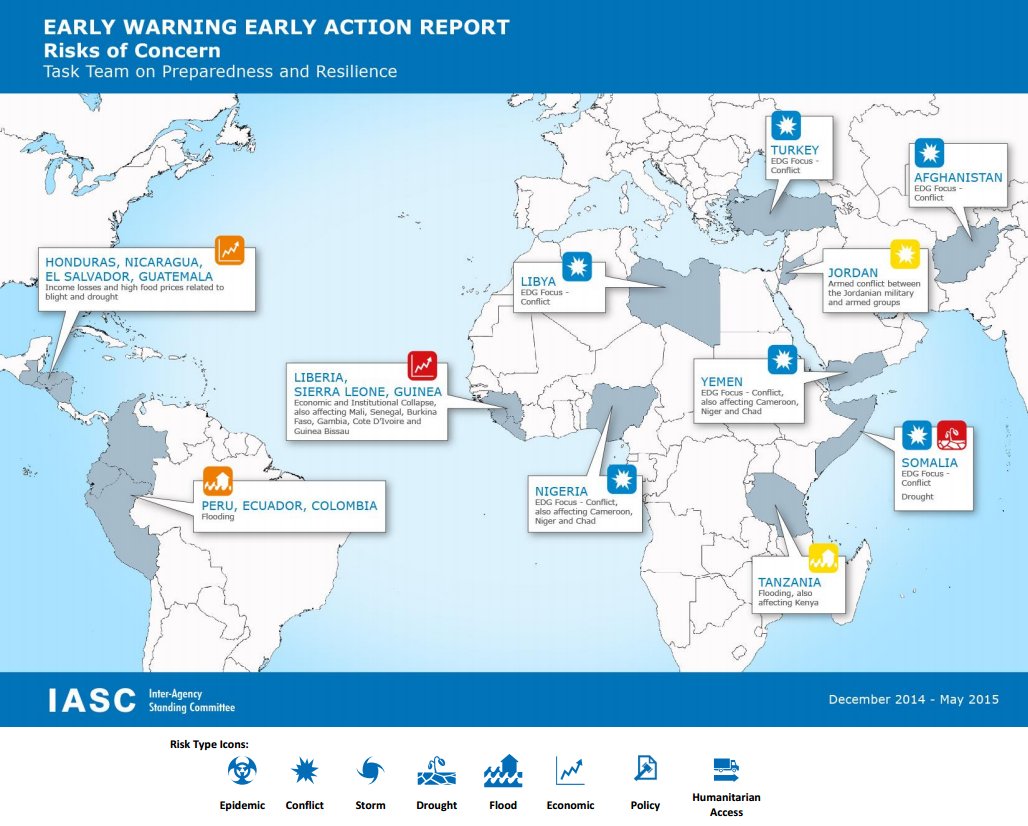

Predictions of this kind are essential to get everyone in the humanitarian community prepared for the next emergency. And in a 2-page document that anyone can find on Internet, there is a map of the emergencies foreseen by the UN for a 6-month period ending May 2015 (this one came out in December 2015 – screenshot):

Eleven hot spots, eleven areas in the world where chances are very high –close to 100 percent – that people will die in large number soon if nothing is done. It’s an amazingly high number.

This document, of course, cannot take into account unpredictable disasters, like an unexpected volcano eruption, an earthquake (for example in Haiti in 2010) or a tsunami (the December 2004 in South East Asia); nor does it take into account “smaller” emergencies like the on-going one in Mali (currently under the watch of France more than anyone else).

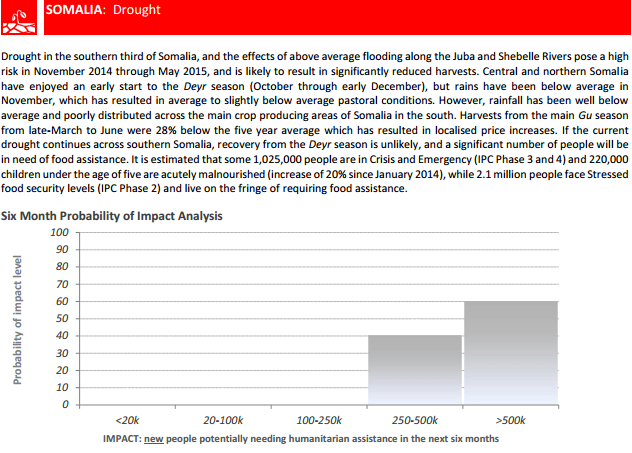

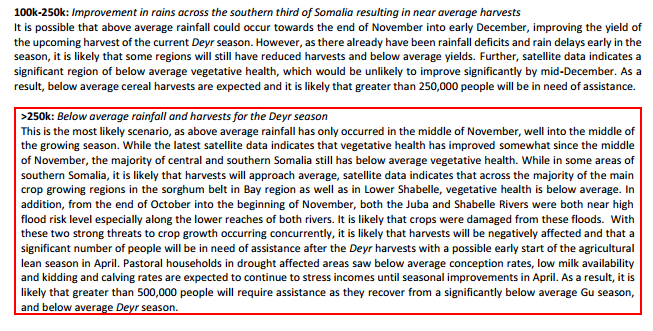

But it focuses attention on the major ones, and among them, on the particular one that is expected to be the worst of the lot, and it’s not going to happen in the country you might expect, say Syria or Libya – but in forgotten Somalia, it’s presented in red, the highest alarm level (screen shot):

The worst case scenario is dire:

In short, because of prolonged drought, more than 500,000 people will require assistance sometime in May-June 2015, if not before.

Alas, this is not the first time that a catastrophic drought has affected East Africa: the last big emergency was in 2011. So, understandably, there is a certain degree of donor fatigue…and a lack of interest from the media. But the United Nations never gives up.

When the time comes, on the basis of all this information the people behind this map are continually gathering – including satellite data, as you may have noticed if you’ve read the screen shots above – an appeal for funds will be launched and efforts organized to provide aid.

At this point, you may wonder who exactly is behind this map.

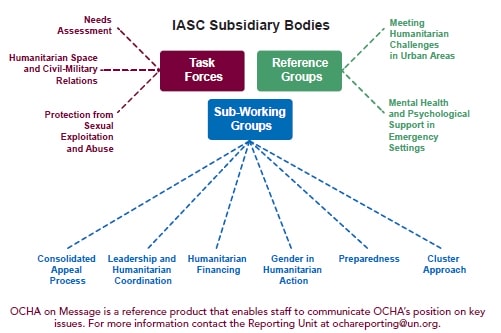

It’s called IASC, that’s for Interagency Standing Committee. I can hear you groan Committee of what? Bear with me. It’s a UN mechanism for coordinating the international community’s efforts to provide emergency aid. It brings together all the major humanitarian agencies in the world, not just the top UN specialized agencies (like UN Refugee Agency, the World Food Programme, UNICEF etc) and the UN Development Programme and World Bank but also all the major international non-governmental organizations, like the Red Cross (ICRC) and Red Crescent (IFRC), a total of 18 organizations.

How does the IASC work? This is the structure:

And it works in many ways: through guidelines so that humanitarian agencies not only work together in an emergency but work in the same way; through information gathering about the emergency, how big it is, how it develops, where it’s headed so that it provides appropriate aid as soon as possible (i.e. predictions about future emergencies like the one shown here); and through constant exchange of information among the IASC members (emails etc) that enables everyone to get ready in anticipation and prepare for the emergency as soon as possible. It is to every members’ best interest to participate and toe the line to avoid duplication of efforts and waste of time, hence, the IASC truly functions as an engine of coordination.

I discovered all this fortuitously, in the course of my research for my next book – an analysis of what the United Nations has achieved over its first 70 years of existence (it was founded in 1945) and where it’s going. Yesterday, by chance, as I was reading the International New York Times, I came across this emotional rant from a free-lance journalist, Rosalie Hughes, who had worked for the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) during the war in Libya, directing to refugee camps people who were escaping into Tunisia.

In the photo: Refugees from Libya Find Shelter at Tunisian Transit Camp – 06 March 2011 – UN Photo/OCHA/David Ohana

In the photo: Refugees from Libya Find Shelter at Tunisian Transit Camp – 06 March 2011 – UN Photo/OCHA/David Ohana

She reported suffering from paralyzing bouts of anxiety and, on the basis of her own experience, concluded that “Depressed and anxious aid workers perform poorly,” adding that there was data to prove this: “In 2012, psychiatric conditions were the leading cause of missed work among UN refugee agency staff members.” But, she noted, “Statistics don’t exist on the number of people who quit due to burnout, but I personally know at least half a dozen. I am one of them.”

Burnout is no doubt more prevalent in humanitarian aid work than in any other line of UN activity. While the UN has from the beginning of its field operations set up special rules for hardship posts, for example increasing the frequency and length of rest time away from the post, there is no doubt that more psychological support is needed, particularly for workers in war zones that may suffer from assault and post-traumatic stress.

So I decided to further research the issue and I discovered that, historically, the humanitarian crises of Cambodia and Bosnia-Herzegovina and Croatia in the 1990s were a turning point, as they drew the world media’s attention to the plight of humanitarian workers suffering from PTSD.

Then I came across the IASC – that’s how I discovered how they work – that had set up a so-called “Reference Group” (see chart above) in 2005 to review the problem. In 2007, the Group issued guidelines on how best to provide psychological support to both the victims of disaster and aid workers, available in many languages, including Tajik and Nepali. A little later, I came across – it is almost like a Sherlock Holmes investigation –an important evaluation of that psychological support to staff that was commissioned by UNHCR in 2012 to an outside expert, Dr. Courtney Welton-Mitchell of the University of Denver (it came out in 2013, see report here).

The evaluation findings were devastating: UNHCR found itself accused of a “lack of adequate response to critical incidents”; inadequate utilization of existing psychological support services; “lack of adequate support for informal peer networks, apart from the underutilized peer support network”; and a “lack of accountability for the adequacy of [psychological support]services provided, in part due to minimal evaluative efforts, including a lack of formal means of collecting indicators on staff well-being and satisfaction with existing services.”

Detailed recommendations were made to address these points, particularly to strengthen overall psychological support services, including informal peer support networks, and accelerate response to incidents and make it more appropriate (like, for example, transferring victims of PTSD to low-risk areas), and of course, ensure that staff welfare services are regularly evaluated in future.

The follow-up? There is clearly a way to go. UNHCR faces a crisis in MHPSS (Mental Health and Psychological Support) activities not only for its staff but also for what it calls “persons of concern”, i.e. refugees, displaced and stateless persons, as pointed out by another outside evaluation, also done in 2013. That evaluation seems to have resulted in better support to disaster victims.

But what about UNHCR staff? I haven’t been able to discover if any further measures have been taken by UNHCR in this area – though I assume they have, a negative evaluation usually provokes a (healthy) reaction. Nor, for that matter, did I find any trace of discussion of this issue in UNHCR’s Executive Committee (its governing body where delegates meet regularly to address issues in UNHCR’s work). I’d welcome any information about this from anyone in the know. In rushing to aid victims, we cannot forget aid workers who risk their lives and do all the hard work.