I grew up in Boston in the 70s and 80s, not too far away from where Thoreau once lived. My family shared his belief that nature was a vehicle towards transcendence— that spending time quietly contemplating the land, sea, and sky could bring us closer to an understanding of God and more in touch with the goodness inside all of us. We loved spending time outdoors. We hiked, camped, and swam in the mountains and beaches nearby; and we enjoyed walking in the city and playing in its beautiful parks.

Yet, I’m not quite sure we were environmentalists. We loved the natural world, but we also seemed to take it for granted. It was there for us to appreciate and enjoy, but we did not necessarily need to fight for it. We did not need to devote our energies towards caring for it. We recycled, but we also bought our share of disposable plastics: bags, cups, forks, plates… We offered charitable contributions to environmental organizations, but we weren’t out on the streets protesting environmental policies. We were certainly aware that pesticides, oil spills, and other forms of pollution threatened the beautiful landscape that we loved so much; but we didn’t really talk about these problems so often, and we certainly weren’t spending weekends actively trying to fix them.

We did talk about Judaism quite a lot, though—especially after my parents discovered Orthodoxy. My siblings and I were sent to a Yeshiva, where we spent much of our time praying or studying the Bible, the Talmud, and other religious texts. Myriads of laws and rituals filled our lives. Most of them focused on our behavior towards other people and towards God. Very few of them had much to do with our responsibilities towards other species and the Earth. We cast our sins into the water during a ceremony called Tashlikh. We thought about all the aveirot (transgressions) that we did towards God and towards each other; but I don’t recall much discussion about our sins towards the Earth and other species. We learned that God gave water the power to absolve us during Tashlikh and to purify us at the Mikveh (ritual bath). We didn’t seem to worry too much about whether water would still have the capacity to heal us if we kept polluting it.

We, like most Americans, were largely disconnected from the environment. How and why would we focus on our environmental responsibilities when no one else around us seemed to be doing so? Yes, there certainly were (and are) religious and secular communities (including many Jewish ones) who emphasized environmental responsibility more than we did; but they seemed like they were from another world. We were city folk. None of us were farmers. We, like most everyone else, purchased packaged food (even if not exclusively) and other objects wrapped in plastic in ways that obscured and abstracted their origins. The Jewish rituals that we did could almost all be done indoors, in the city. We read about prophets wondering alone in the desert and mystics singing and dancing in the forest; but those were actions for other, special people. Israelis worked on communal farms, planted trees, and turned deserts into farmland; but that was millions of miles away and culturally even more distant.

In the photo: Screens of the underwater video installation. Image credit: Joel Tauber, UNDERWATER installation at KOENIG2 by_robbygreif (installation photo: Masha Sizikova)

Or, so it seemed to me before I was 18. Then, even though I was valedictorian of the Yeshiva; I decided to leave organized religion behind me. I continued to very much believe in God, but I felt oppressed by all the laws; and I wondered if I could develop a personal spiritual practice beyond the walls of the synagogue.

I was a city boy, but I wanted to get more in touch with the Land. So, I joined a kibbutz in Israel. I woke up at the crack of dawn each day and picked carrots in the fields. My hands got dirty, and I loved it. It was beautiful, and at times even transcendent—just as Thoreau promised. I wanted more, but the kibbutz had other ideas; and I was sent to work in a salami factory. The salami factory was far from a transcendent place, and it made me to start wonder if I should stop eating meat. Then, I started worrying about the reports that Iraq was getting ready to launch a series of missiles into Israel. A combination of fear and ambition took hold of me, and I returned to the States to begin my studies at Yale.

I loved living in America again, this time unencumbered by the restrictions of Orthodoxy. I felt free, and it was exhilarating. Yet, I began to feel increasingly uncomfortable by how our culture celebrated that freedom to such a great extent. There was a lot of talk about the individual and the material pursuit of happiness, but there seemed to be a lot less discussion about our responsibilities beyond ourselves.

I felt that this conversation was sorely needed, so I decided to do what I could to spark it. I started making art about ethics, environmentalism, and mysticism. I chronicled my attempts to engage the Other—not just God and other humans; but also the land, the sea, the sky, and other species. I developed personal, idiosyncratic projects over the course of more than two decades; as I wrestled with how to try to live an ethical, environmentally conscientious, and spiritual life without relying on the moral compass of organized religion or other institutional norms.

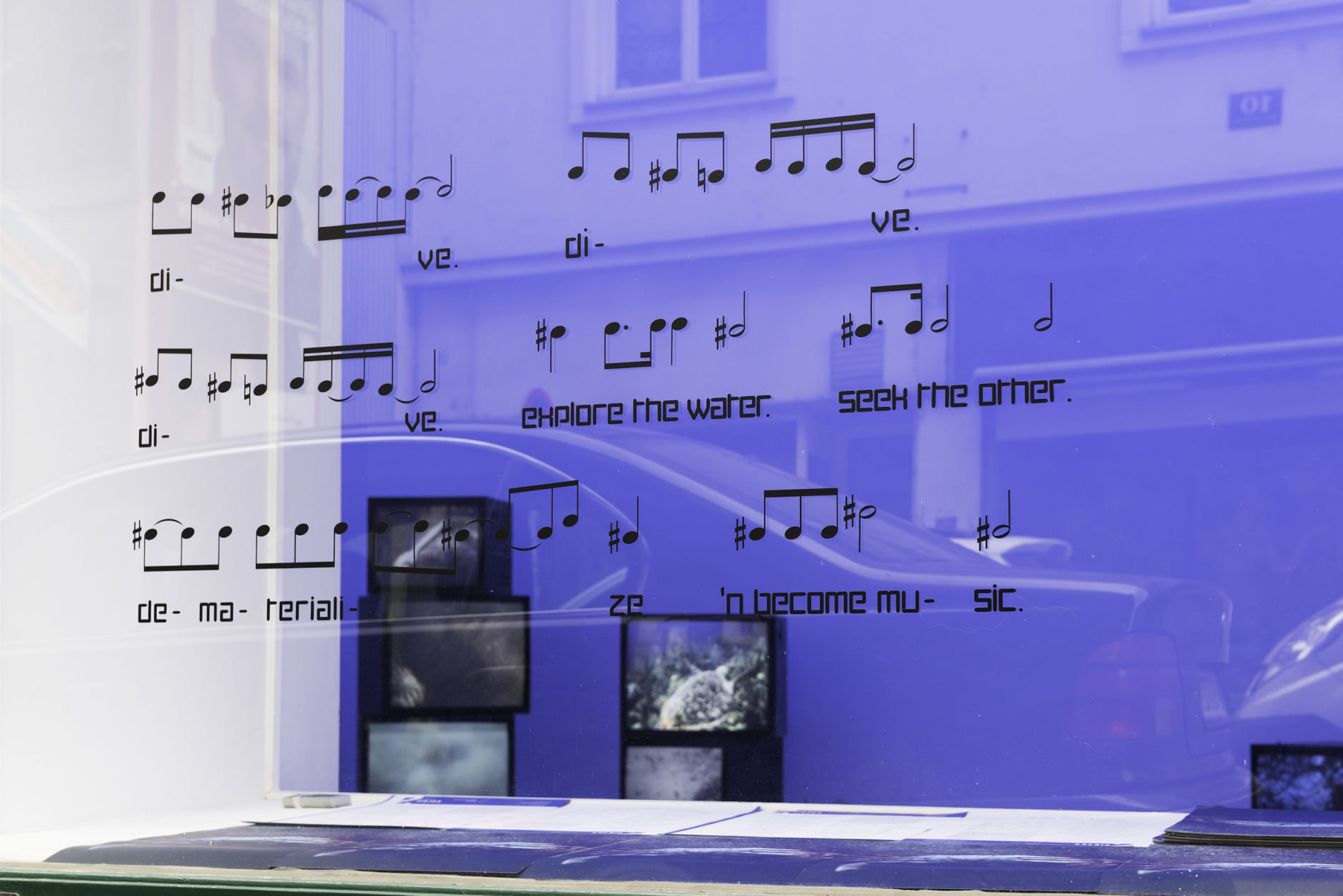

In the photo: Images of the underwater video installation and the one of the songs to go along with it. Image credit: Joel Tauber, UNDERWATER

I began one of these projects by scuba diving off the coasts of southern California and Belize. I wanted to reach a greater understanding of the underwater world and its many inhabitants, and I hoped that exploring the water would also lead to at least some spiritually transcendent moments. And that certainly did happen. I was awestruck by a gorgeous sea turtle who allowed me to swim with him/her for about 4 minutes, and I was mesmerized by the swaying kelp and gorgeous sea grass that I encountered.

Yet, I was also deeply troubled by the signs of pollution and environmental devastation that I found. Plastic sporks sitting on the sea floor. Dead crabs slowly turning over and over, forever lost at sea. How could I hope to achieve spiritual enlightenment from the oceans that we’ve polluted so terribly? And, how could the waters absolve our sins, if we kept harming them?

I didn’t know the answers to these questions, but I believed that any pathway forward could only begin with the realization that we are deeply connected to the Ocean and all who live there—whether we want to be, or not. I felt heavy and self-contained in all of my scuba gear. I wanted to free myself from my individual, material shell. And, I wanted to collapse the boundaries between myself and everything around me.

So, I created UNDERWATER: a 7-channel video installation that brings environmentalism, trance music, and mysticism together. It suggests, in interactive and immersive ways, that we’re all connected to each other and to the land / sea—even if we have largely forgotten that and even if we have to collectively change our ways. As people dance in the UNDERWATER operatic disco, their movements—which echo my own—blur the distinctions between our bodies. The boundaries between the Self and the Other collapse; just as the distinctions between people / marine life blur, and the distinctions between the human built environment of the exhibition space and the underwater video world merge.

In the photo: A dead crab floating along the sea bed. Image Credit:Joel Tauber, “Death”, video still from UNDERWATER

5 videos focus on what I find underwater: pollution, death, nausea, a beautiful sea turtle, and swaying kelp… A 6th video shows me disappearing into a cloud of air bubbles; and a 7th video shows a visual map of my 40 scuba dives, which slowly moves into existence from left to right in real time with the 51 minute musical piece.

The composition arises from depth readings recorded during every second of my dives. I assigned each dive an instrument and a beat and translated the movements of each dive in real time into music: the deeper the depth reading, the deeper the note. Sometimes, all 40 dives play together. Other times, a “band” of dives are heard. And, then there are moments when individual dives have “solos”. I sing my dive depths (higher notes for the higher depths, deeper notes for the deeper depths) (“43 feet”… “80 feet”…) at various intervals to emphasize the relationships between my movements underwater and the music.

I sing about seeking the Other (which is the chorus) in ways that evoke the Jewish cantorial scales; and I sing about what I find underwater in ways that evoke the iconic old melody “Kol Nidre” from the Jewish Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur. So, there is a prayer-like / collective atonement element to this underwater rave.

The videos are projected on walls, floors, and ceilings. Alternatively, old school cathode ray monitors are stacked on top of each other, like sea stones. 8 drawings of the musical notes and lyrics in the composition surround the videos, and overhead neon blue lights illuminate the space.

Participation in UNDERWATER can happen both directly, by experiencing the installation and dancing to its music; and also remotely by responding to the call to send in personal stories about global warming, marine life, seas rising, and hurricanes. Stories sent to mail@adamskigallery.com will be included in the upcoming exhibition of UNDERWATER at the Adamski Gallery For Contemporary Art in Berlin.

The show at the Adamski Gallery will open in May. The gallery is located at Fahrbereitschaft, Herzbergstrasse 40-43, 10365 Berlin; and it is open Tuesday – Saturday from 12-6 pm and by appointment (Phone: +49 151 15773221. Email: mail@adamskigallery.com).