Beyond the daily horrible visuals on the news, and beyond the increases in oil and gas prices at the pump or the heating bill, the reach of this war extends to your table – if you have one to eat from, or if you have prospects of a regular meal. While there are many ways in which food prices will be affected, from the farm to market delivery to the individual, there is one basic for many people in the world that will be directly and significantly affected, and that is wheat.

The Overview

Wheat is a global commodity and futures already have risen by about 40% in 2022, thus contributing to the broader global inflation surge as economies are already working to recover from the two-year coronavirus pandemic. This is in part due to the fact that major wheat exporter stocks – the European Union, Russia, the United States, Canada, Ukraine, Argentina, Australia and Kazakhstan are projected to fall to a nine-year low by the end of the 2021/22 season, according to the International Grains Council (IGC), and this before taking into account the ongoing conflict.

The Russian Federation and Ukraine together account for 29% of global wheat trade, with Ukraine roughly 12% as the fourth largest global exporter. As the Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered supply disruptions from what are essentially two of the world’s largest grain producers, the Chicago wheat futures reacted as one might expect, surging above the $12-per-bushel in early March, a level not seen since March 2008.

A major reason is the policy response of the West to the Ukraine war: Heavy sanctions and restrictive measures against Russia that were quickly adopted by the western government are beginning to bite, and in particular, they are nearly halting exports from the Black Sea.

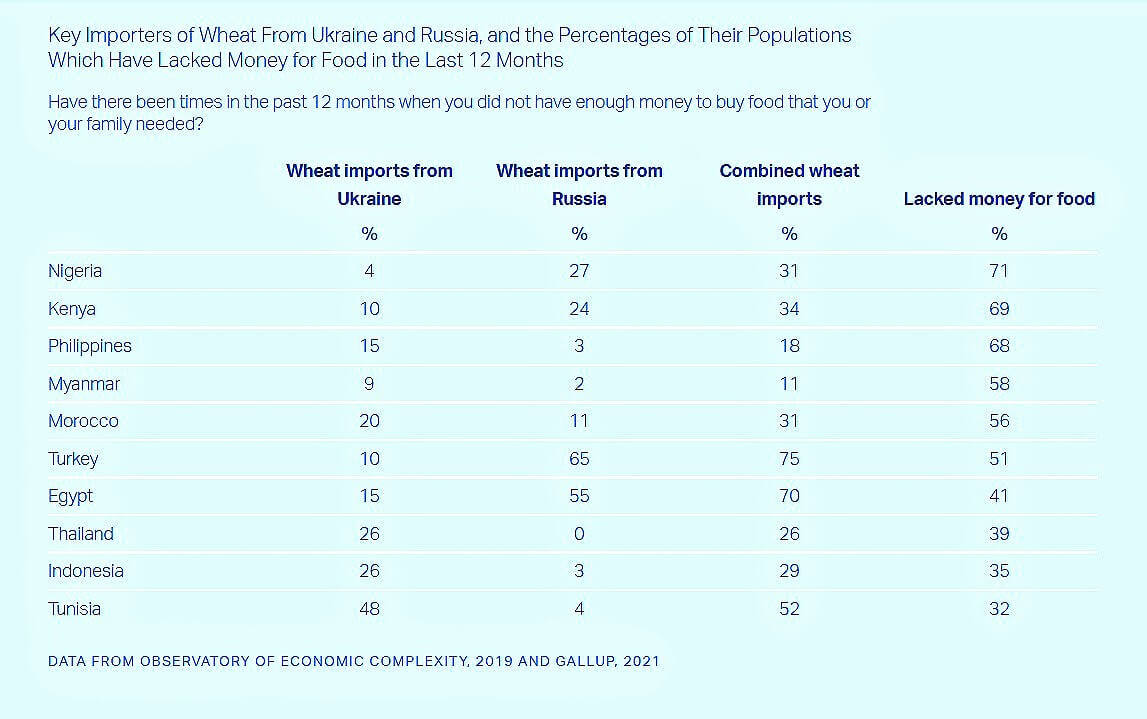

Key Importers of Wheat from Ukraine and Russia

As the above table strikingly shows, countries most dependent on wheat imports from Ukraine and Russia are spread in three regions: in the Middle East, Turkey (for 75% of its wheat imports), Egypt (70%) Tunisia (52%) and Morocco (31%); in Africa, Kenya (34%) and Nigeria (31%); and in Asia, Indonesia (29%) and Thailand (26%). Turkey and Egypt are especially dependent on Russia (for 65% and 55% respectively) while imports from Ukraine are more evenly distributed, but are particularly important for Tunisia (48%) and substantial for Indonesia and Thailand (both get 26%) and Morocco (20%)

In sum, expect a stop in Russian and Ukrainian wheat supplies to hit especially hard the Middle East and two countries in particular: Turkey and Egypt, although the rest of the world won’t be spared.

What is of special interest is the additional question Gallup pollsters asked in their survey: “Have there been times in the past 12 months when you did not have enough money to buy food that you or your family needed?”

The answers (also shown in the above table) reveal that people who are most likely to suffer the most are those living in Africa, in Nigeria (71% indicated they didn’t have enough money) and Kenya (69%); but the next group of big sufferers is found, perhaps surprisingly, in South-East Asia: the Philippines (68%) and Myanmar (58%).

This said, the rest of the countries in that table are not doing well either – in Morocco and Turkey, over half the people surveyed reported they lacked money for food. Even Tunisia, reputed to be the most “advanced” and democratic country in North Africa and the Middle East sees one-third of its population suffering from insufficient budget to buy food – and to buy such a basic necessity as wheat (read: bread).

Given supply chain issues created during the COVID-19 pandemic, food security had already become a higher priority in most major importing countries, especially the low and low-middle countries. And now the Russian invasion of Ukraine is turning what was a problem into a tragedy.

Effects on Ukrainian agriculture – Wheat production is hit

While there is limited reporting on what is happening at the farm level in Ukraine, transport throughout the country has been severely affected, as has access to needed power there and at granaries.

Getting wheat to a port and then having it loaded onto a ship and exiting the Black Sea is all precarious, to say the least.

For those in the Ukraine, current and future food deprivation is threatening, especially in urban centers now rapidly emptying of people – so far, over 1.5 million Ukrainians have escaped and the UN expects that number to reach 4 million (nearly 10% of the total population). The Ukrainians who leave the country are mostly women, children and older people as men between the age of 20 and 60 have been conscripted and enrolled for fighting. In fact, food shortages in Ukraine have already happened and are reported in the besieged town of Mariupol on the Azov Sea. a place of refuge for literally millions, theirs is fraught with current and future deprivation.

Despite its significant domestic production, reasonable storage capacity, stocks, and preparation, Ukraine, a country of 44 million people, has and will continue to have major shortages of food even once this war has ended.

With respect to wheat, the cycle from planting to production depends on the availability of seeds, fertilizer, pesticides, climate, and harvesting manpower and equipment. Here the main planting season is in Autumn (with roughly 16 million acres under cultivation) and a later one beginning in March.

Before the war, estimates were to have 26-27 million tons produced, but that is now down to 16-17 million tons. Expectations from observers are that “Ukraine requires around 10 million tonnes of wheat for domestic consumption. Depending on the scenario, that will leave between 6 and 17 million tons available for export through the 2022-2023 marketing year from June to July.”

Wheat export shortfalls: Hunger hotspots threaten DFICs (Developing and Food Insecure Countries)

Staple grains supply the bulk of the diet for the world’s poorest. Higher prices threaten to place a significant strain on poor countries like Bangladesh, Sudan, and Pakistan, which in 2020 received roughly half or more of their wheat from Russia or Ukraine – and as shown in the above table, particularly in Egypt and Turkey, which imported the great majority of their wheat from those combatants.

UN Agencies warn of impending food shortages in developing and food-insecure countries. Experts from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) expect food insecurity to increase, becoming acute as the situation deteriorates, further affecting 20 countries during the outlook period, from February to May 2022.

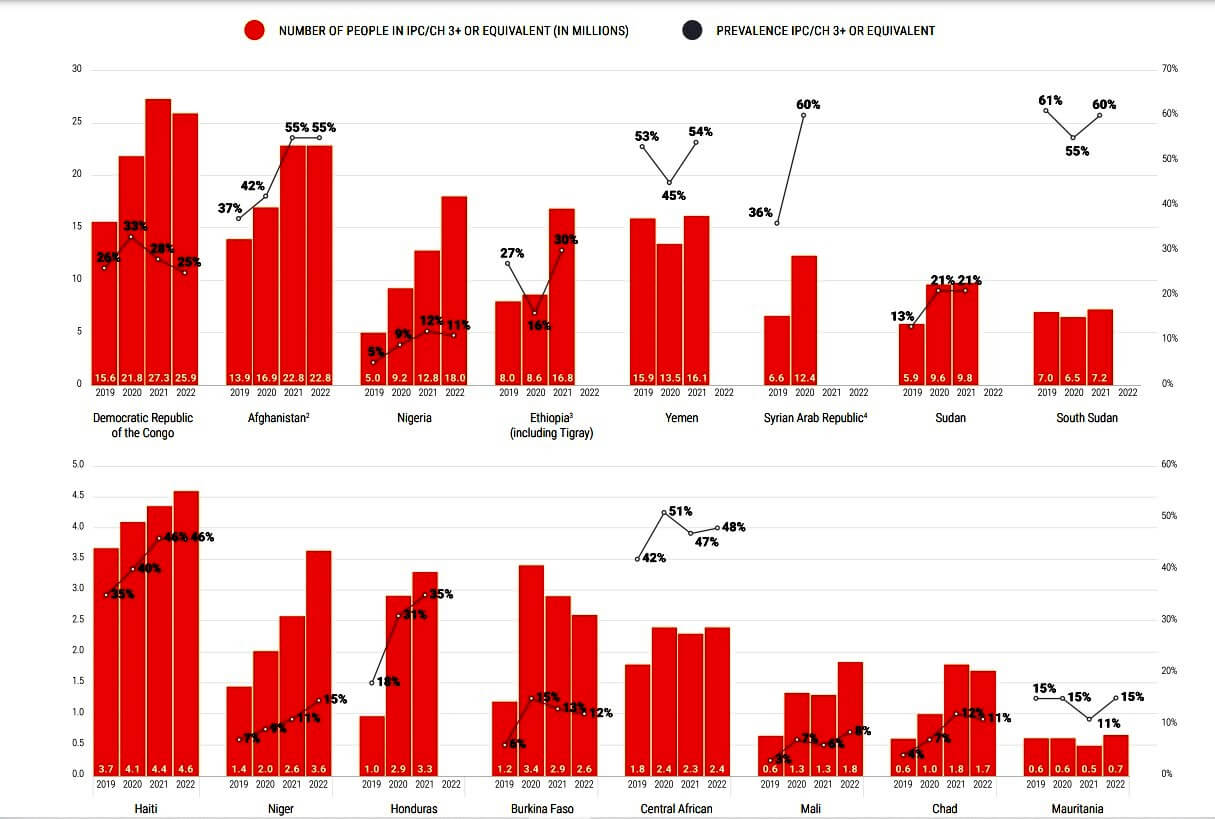

Africa has the most countries at the highest level of alert: D.R. Congo, Nigeria, Ethiopia, followed by Niger, Sudan, South Sudan, and others; then Asia has the devastating (and new) case of Afghanistan, and Latin America continues with Haiti and Honduras; the Middle East with Yemen and Syria.

These countries all had parts of populations identified or projected to experience starvation and death – as per the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification [IPC global platform] of countries requiring the most urgent attention.

To be clear: Just as we have “virus hotspots” from which disease and future pandemics could emerge, we have “hunger hotspots”, this time as a result of the war in Ukraine. The following table shows where those hunger hotspots are:

Acute food insecurity trends in hunger hotspots of highest concern

2019–20221 peak numbers and prevalence, ordered by magnitude of latest peak number

Ukraine was the second-largest supplier of wheat to the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) in 2020 and 2021. Unable to procure wheat from Ukraine, WFP will likely have to purchase the grain from other, more expensive sources and thus have less aid to provide to those at the greatest risk. WFP estimates that the cost of food (not just wheat) will mean an operation price hike of from $60-70 million per month.

The Future

There are too many uncertainties to make anything that resembles a forward outlook. What is certain is that the numbers of people without adequate food, many of whom look to wheat as their staple grain, will grow.

When a major source of a food commodity is severely shrunk, the ripples extend not just to it, nor countries looking directly to it for supply, but to all of us. Those many countries which are amongst the leading wheat exporters need to plant more, much more, now to stave off another unnatural disaster.

Featured Photo: Wheat harvesting