For several weeks we have been on the edge of our chairs with worry about whether a major war will happen in Ukraine, with Russia and the West playing a frightening game of who will blink first, potentially on the brink of a major military conflict. As I write, events are accelerating. Russia has accumulated more than 150,000 troops around Ukraine and US Secretary Blinken went to the UN Security Council on February 17, leaving little room for optimism. On the same day, US President Biden issued an unusually dire warning that Washington saw no signs of the troop withdrawal promised by Russia and Moscow expelled the number 2 American diplomat. Today AP reports that Russia is staging “massive drills of its nuclear forces”, involving multiple practice missile launches.

A continuing concern is that the longtime separatist conflict simmering in eastern Ukraine could provide the pretext for an invasion.

All this is happening while globally we continue to struggle with the COVID pandemic, with dramatically different approaches and levels of infection. A new and more virulent Omicron variant (BA.2), has just been identified and with it likely other variants will emerge in the future.

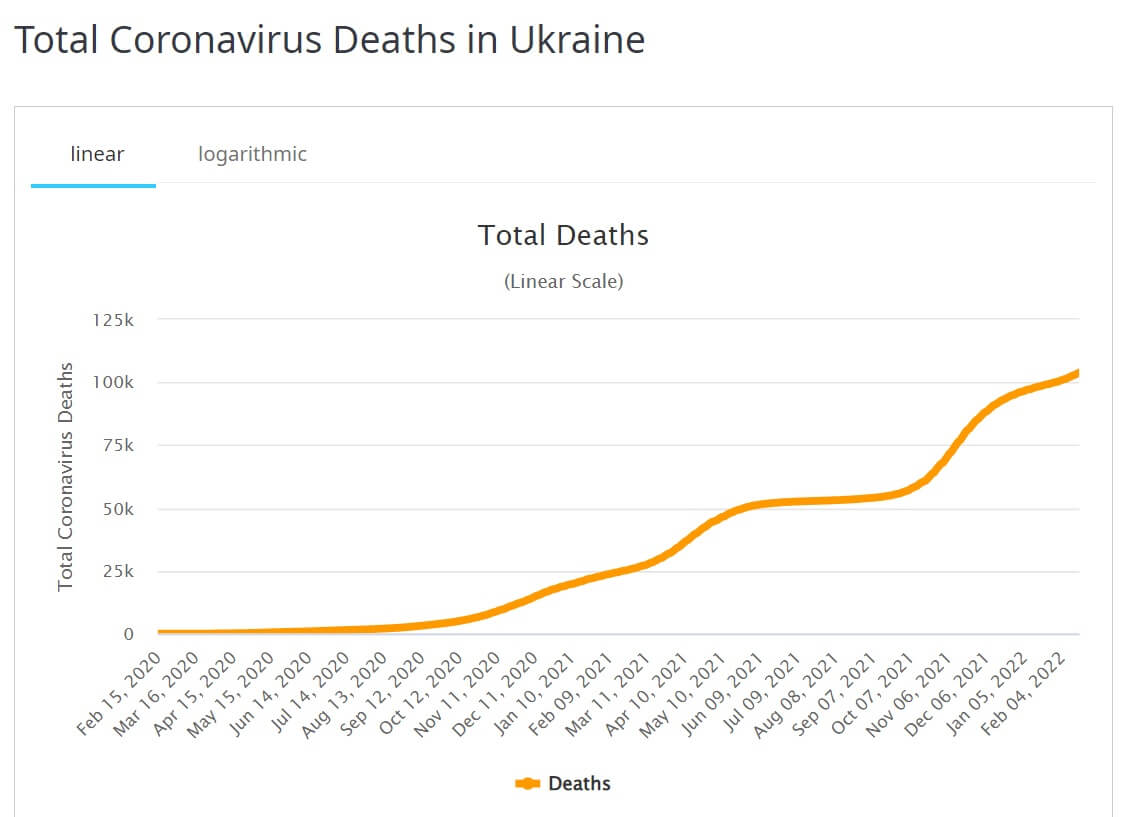

According to the latest available information, since records have been kept in Ukraine, over 4.6 million COVID cases have been reported and 103,500 deaths, with new cases increasing significantly in January-February 2022, including nearly 30,000 new cases and 310 deaths on February 16th.

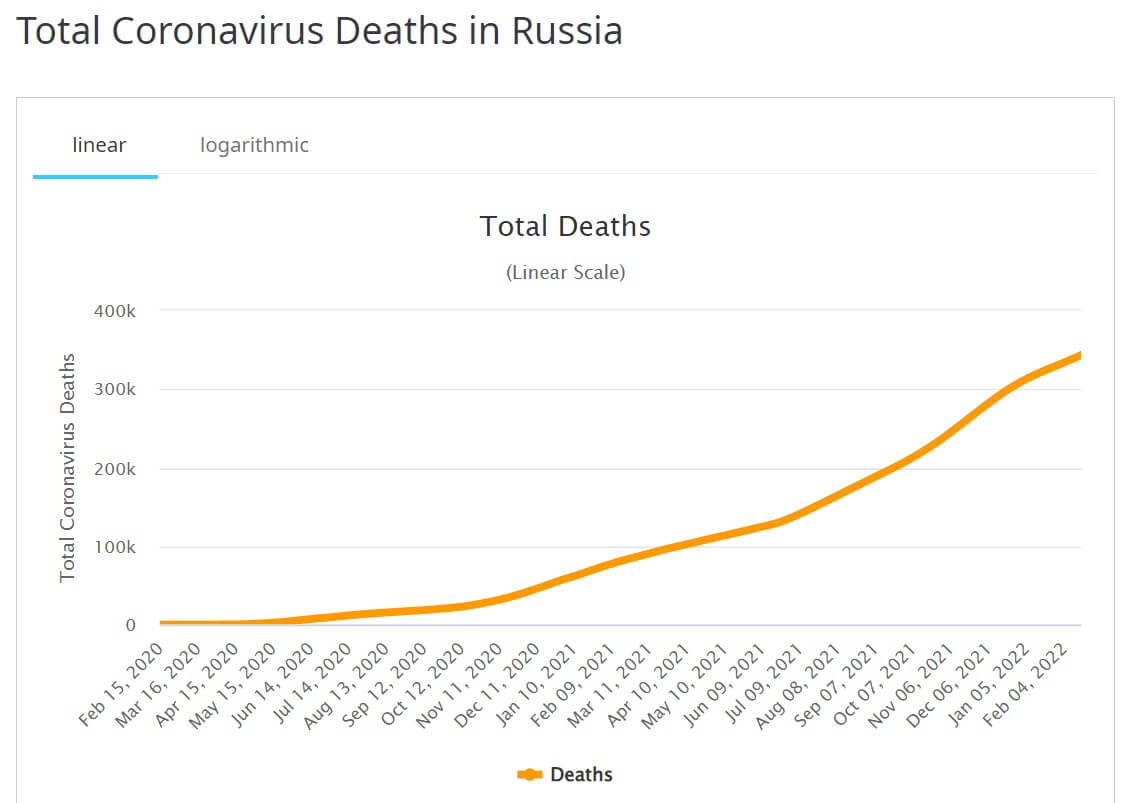

Russia, since data began being collected, has already had over 15 million COVID cases, over 340,000 deaths, and in the last two weeks nearly 2.5 million new cases.

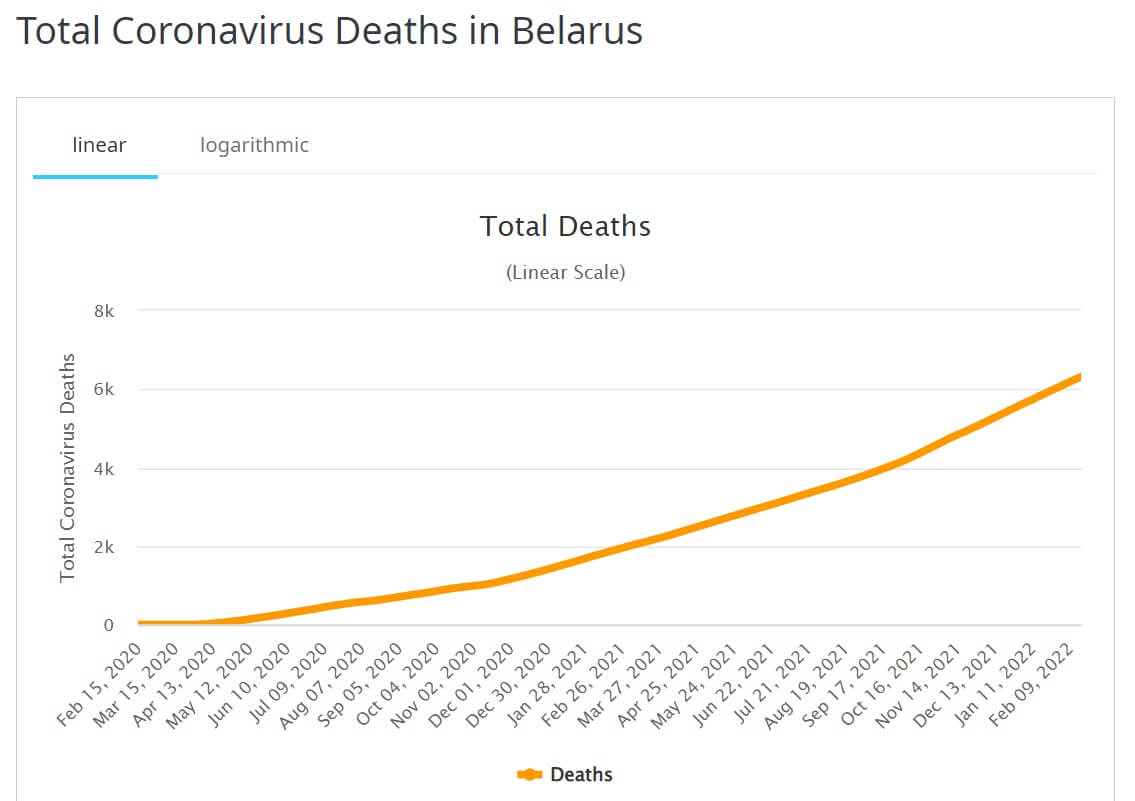

Belarus, which is Russia’s ally and military training exercise partner threatening Ukraine, has a much smaller population than either Ukraine or Russia, yet it has had over 860,000 COVID cases, over 6, 300 deaths, and almost 99,000 cases in the last two weeks.

The trends in each suggest that neither vaccines nor conventional containment measures are working to good effect.

What we know about the impact of armed conflicts and infectious diseases

Armed conflict can be found in many parts of the world, caused mainly by ethnic, cultural, and religious factors. The majority are located in low- and middle-income countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia where socio-economic and health problems are closely linked.

Armed conflict has wide variations in terms of its impact on infectious disease transmission, often depending on the geography, limitations on travel, health system services, and duration. Sub-Saharan Africa in particular has experienced a number of infectious disease outbreaks such as HIV/AIDS and Ebola. Ironically, relatively short civil wars affect inter-country travel, and this can limit transmission because of reduced inter-personal contacts. Longer ongoing strife, such as in the Middle East and Syria/Lebanon, will have lingering negative effects.

What is essentially different with Ukraine is that it is Europe. While not without conflicts in its recent past (notably the war in the Balkans), this continent has not experienced an event with major civil disruption, destruction and casualties, and loss of human life – at least not since World War II. European countries along with Russia are modern societies with substantial health professionals and services, educated populations, good internet, and communications systems.

What is a certainty is that whatever the length or nature of any armed conflict in Ukraine, it will have a negative effect on health systems, disrupt surveillance and response systems, and result in an uptick in known, preventable infectious diseases; even more so with COVID and any future variants. The weakened infrastructure will prevent access to healthcare and ordinary emergencies, for both civilian and military populations.

That the military on both sides will be affected, we know from history.

During the Napoleonic Wars, infectious diseases were responsible for eight times more deaths among British soldiers than wounds suffered during the fighting. Infectious diseases were among the main causes of deaths among soldiers during the Swedish–Russian war in the late 1780s. Until World War I, infectious diseases rather than battle and non-battle injuries were the main causes of morbidity and mortality among soldiers, as well as in the affected civilian populations.

Indeed, infectious diseases were referred to as the “third army” during an armed conflict.

By World War II the impact of many infectious diseases as causes of mortality or morbidity within the military had changed; they had gone from presenting potentially lethal threats to being primarily curable illnesses

But with the advent of COVID, an infectious outbreak has returned as a major cause of morbidity and mortality for both the military and civilians.

What “If”?

With both Russian and Ukrainian populations showing increases in COVID infections, a significant military incursion would likely severely hamper Ukrainian Government efforts to contain further COVID spread.

Not only would the health system be less able to provide tests, vaccines, and medications, but there would be a heightened possibility of a spike in transmission as people spent significant time in underground bunkers in tight quarters such as the subway system in Kyiv.

For the Russian military, it is likely to have brought with it medical teams. There are reports that the Russians have set up field hospitals and facilities along the border with Ukraine and many observers see this as a further sign of an imminent Russian invasion.

So one might expect that COVID infection levels will be similar to the rest of the Russian military and population, unless contacts with Ukrainians translate into additional exposure. Belarus would probably be doing no better or worse than before the “training” exercise with Russia on the Ukrainian border.

In sum, in the event of war COVID variant case numbers are likely to worsen in all three places. To comment on possible seepage to other nearby European countries would be sheer speculation, but one could envisage it as a non-kinetic threat to NATO members. Hopefully, none of this will come to pass; recognizing the possibility, taking preventive and preparatory measures, nonetheless would make eminently good sense.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. In the featured image: A Russia-backed rebel observing Ukrainian army positions though firing port at his position near Donetsk, Eastern Ukraine. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.