In gay culture, the expression “coming out” was initially borrowed from the world of debutante balls. But in the 1960s, the phrase came to refer to being in hiding when “from the closet” was added. In recent decades, pared down to the original “coming out,” it has typically come to refer to proudly expressing one’s homosexuality to the world. The abbreviated version has also been adopted by the trans community, which has been the focus of perhaps unprecedented media attention in the last year. In today’s day and age, people can now be loud and proud of their gender identity thanks to accessories like the lgbt pride pins.

Of course, the fact that gender identity does not always match biological sex is not news. The world was captivated by Christine Jorgensen, an American transgender woman who transitioned in the 1950s in Europe. She had first traveled there after being drafted into the U.S. Army. Following sex reassignment surgery and hormone treatments, she returned to the U.S. and welcomed taking on the role of transgender spokesperson. Actual sex reassignment surgery dates back to the 1920s and ‘30s in Germany. But Ms. Jorgensen became the first person to also benefit from the addition of female hormone therapy, as did Renée Richards, American ophthalmologist and former professional tennis player, who started with hormone therapy before having surgery in the 1970s. Caroline “Tula” Cossey, a British model who transitioned in the 1970s also, was outed as transsexual after she performed as an extra as a “James Bond girl” in the 1981 movie For Your Eyes Only.

Terms such as transgender and transsexual have been used, often with questionable understanding, for several decades. Along with the knowledge that not every person who identifies as transgender has surgery, and that transgender identity is not as uncommon as once thought, the expression “cisgender,” individuals whose gender identity matches their biological sex —itself around for less than 20 years—has slowly pierced the awareness of the culture at large in recent years.

Marriage equality, which reverses entrenched discrimination based on sexual orientation as well as gender identity, is one of many encouraging signs of a much more inclusive culture. But acceptance, compassion, and fair treatment have come in fits and starts, especially for the trans community, and full equal rights remain elusive.

Sexual minorities continue to face a much higher risk of being confronted by prejudice and violence, particularly those who identify as trans men or trans women. Each step in a more equitable direction seems to be tempered by mean-spirited discriminatory laws, such as North Carolina’s so-called “bathroom law” HB2 (which among other provisions and without clear enforcement mechanisms, restricts people to using public bathrooms based on biological sex at birth).

In a more optimistic spin, though, the U.S. Department of Justice and local communities, as well as a nationwide boycott, have come to the defense of transgender people in North Carolina. And the National Basketball Association has joined the boycott by opting to move its all-star game from Charlotte, NC next year.

Photo Credit: Flickr/Map of the Urban Linguistic Landscape Photography: Jess Andrews

But it was a mere six years ago, in 2010, that the ludicrous “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” law, which expressly prohibited gay people in the U.S. military, was repealed. The law that banned transgender people from U.S. military service remained on the books until July 1, 2016. Of course, we know that transgender people have been serving in the armed forces for decades, but have done so clandestinely, hidden from view and maybe even hidden from themselves.

Sarah Marshall, as Thomas Marshall, was a First Class Petty Officer in the U.S. Navy for six years. She came out as a trans woman in 1996, 15 years after being honorably discharged from the Navy. We discussed her perspective on coming out, particularly when she did, various aspects of life as a trans woman, and issues resonant for today’s trans community.

In the Photo: Sarah Marshall

In the Photo: Sarah Marshall

When did you first sense that your gender identity did not match your biological sex and how did you respond to this realization?

S.M.: At 4 years old. It is the first memory of thought that I have. My response was that I experimented with dressing in girl’s clothes and playing with girl’s toys until I was teased and harassed into suppressing it. When I was young there was no public dialog about trans people. I thought that I was the only one. In fact, I didn’t know what to call myself until I was 10 when I was at a movie with my family. The preview for the 1972 British movie I Want What I Want came on and it was about a transsexual. I completely identified with the protagonist. At the same time I realized that I was not the only person in the world that felt the way I did, my mom said, “That’s sick. How could they make a movie like that?!” The comment sealed the deal for me. Two things shifted internally in that moment that affected my life for years and was unconscious for me until therapy years later. My 10-year-old mind decided that I could never tell anyone about myself. I became the best secret keeper ever. The other thing that happened in my young mind was that I decided that if I couldn’t be who I really was, then I would become the best man ever. That was my path for the next 27 years.

Related article: “IT’S NEVER TOO LATE TO COME OUT”

So, how did you strive to become the best man ever?

S.M.: Joining the Navy was the first major example, which I did after graduating high school. I was born in Hawaii and grew up near Yosemite National Park. The Navy was a way to see even more of the world, on one hand, but, I think my subconscious motivation was really to overcompensate by pursuing a hypermasculine way of life. That’s not unusual for trans women. After I was honorably discharged in 1981, I earned an undergraduate engineering degree at South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. Then I moved to Minnesota to work for 3M, completed an MBA degree, got on the executive track, studied and trained in martial arts, volunteered as a firefighter, and met my eventual wife, Kim.

Did you have an epiphany at some point showing you that you needed to transition?

S.M.: It took awhile longer. Kim and I had moved to the San Francisco Bay Area. I was climbing Mt. Shasta, in California, with a male friend. A ridge that we were passing along began to give way, and I started to fall. My friend caught me at the wrist, and I responded impassively, “Nice catch, Bill.” His reaction to my bravado—that I was full of shit and should have been scared (and relieved!) out of my mind—forced me to reflect on some difficult truths. I expressed no emotion at almost dying because I already felt like the walking dead. I had been writing checks with my body that, eventually I figured, I wouldn’t be able to cash. I felt like I had no capacity for intimacy because I had been hiding or suppressing my true self for so long. So, the truth is, I would have died if I hadn’t transitioned.

Who, if anyone, supported you emotionally through the years?

S.M.: Before I transitioned, no one supported me because I kept the secret to myself with the exception of some of my girlfriends. To them I disclosed that I crossdressed, mostly because I was so suppressed I had no idea that I was a trans woman. Those girlfriends would “put up” with my occasional forays into crossdressing but did not support it. There were lengthy ebbs and flows in my crossdressing periods, too, as I felt disgusted with myself and wrestled with my own internalized transphobia, though I didn’t know what to call it at the time.

When I finally did come out—eight years into my marriage—and started the long process of transitioning, Kim was a rock of support for me. Not that she wanted me to transition. She just wanted me to be happy. Our daughter was born after I had already completed transitioning, so she has only known me as one of her two mothers.

How did you decide on the name “Sarah”?

S.M.: When I was crossdressing and starting to go out in public, I tried a number of test names. When it came down to actually legally changing my name, Kim and I wrote every girl’s name we liked on a white board at home. Then we crossed each other’s names off until Sarah was left. It was a lot like naming our child.

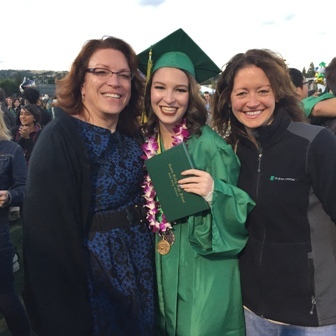

In the Photo: Becca and Sarah

How receptive were others when you began transitioning 20 years ago? Did you have any role models for coming out?

S.M.: It was still a new frontier for the business world. I was an executive at a biotech company. Bless them for enacting a bathroom policy that allowed me to use the women’s room. While I didn’t lose my job per se, after my very accepting boss left the company my career trajectory leveled out, and never regained its male version momentum. I had to behave in an exemplary fashion and prove myself all over again from the ground up. But talent acquisition folks in Silicon Valley ultimately were very complimentary, and that has allowed me to have a successful career as a tech consultant. I had no true role models. There were no trans business executives that I knew of. I was on my own without a road map or even a compass.

Personally, coming out to others has been the most painful thing to do… short of feeling like I was among the walking dead before I transitioned. But I’ve been relatively lucky that my friends and family did not desert me. Each person supported me as they could and/or slowly came around over time. My father died before I transitioned. My mother, who died a few years ago, was never unsupportive. But I had been so virile—the pillar of the family—and she never could completely wrap her head around it, really. She would misuse pronouns and didn’t have a strong capacity to walk in another’s shoes. The younger of my brothers immediately thought it was “awesome,” because it would change his pecking order in the family. I was the first born. My other brother, who is a stone mason and a tough guy, struggled with my transition for a couple of years, but when I arrived for a visit, he introduced me to guests as his sister. Needless to say, that was especially moving. My half-brother was queasy about it initially but has been quite supportive. And new friends came into and continue to come into my life and have been very supportive.

While my daughter Becca has only known me as one of her two moms, as I mentioned, it hasn’t always been easy for her. After explaining her story of how she came to have two mothers, she would be teased on occasion and it was draining for her. Through the years, I’ve shared my story with her, including pictures of my life before her. She is great. And while Kim is wonderful, too, we divorced several years ago when she came to terms with her heterosexuality.

For a full mindmap containing additional related articles and photos, visit #lgbt

Sexual orientation has been understood by many to be separate from gender identity, though some conflate the two. A full understanding of sexual orientation allows for not only a spectrum or range of orientations but some fluidity. How, if at all, has your transgender identity impacted your sexual orientation?

S.M.: Not at all. I was bi leaning toward women before I transitioned and I am still the same.

In the Photo: Sarah, Becca, and Kim

How would you describe the relationship or cooperation between the gay and trans communities?

S.M.: At the time I came out, trans people were the red-headed stepchildren of the gay and lesbian communities. We were not included in the Human Rights Campaign mission statement verbiage or included in the equality equation. The most overt experiences of transphobic commentary and exclusion came from those communities. This was really the case well into the 1990s. We weren’t considered a desirable part of the broader community and, worse, were thought of as a hindrance, possibly delaying equality for lesbians and gay men who were trying to appear “normal.” Trans folk didn’t look “normal” enough.

This changed politically here in California when state senator Mark Leno led an initiative to address trans issues with the City of San Francisco awareness and protection laws. Eventually, Sen. Leno marshaled many of those protections into state laws. In terms of overall support, it has slowly improved over the years. Nothing like this last year in which trans issues have become part of the public conversation across the nation, and internationally.

What kind of an impact on trans life do you think celebrities like Laverne Cox and Dana International or very public transitions, for instance, by Chaz Bono, Chelsea Manning, and Caitlyn Jenner, and even movies such as Transamerica or the TV series “Transparent“, have had? And what are your thoughts on the emerging transgender social awareness and conversation?

S.M.: Overall, they have helped stimulate a public dialog in this last year that has helped me to talk openly with others, particularly in my work environment. Some have said that Caitlin Jenner started the conversation. For me, she’s a Janie-come-lately. So many other trans people have come out, lived, and struggled long before Caitlin came onto the scene. Caitlin did not start a conversation; she created a sensation. To say that Caitlin Jenner represents transgender people is to say that the Kardashians represent humanity. She’s come onto the scene completely resourced, full of entitlement, opinion, and, as far as I can tell, providing zero contribution to her community. So, I struggle with Jenner. She’s a person of privilege who seems to seek attention for attention’s sake. I’m happy for her in terms of her personal journey of transition and glad that she’s helped to put a face on the transgender phenomenon, but I don’t really want her face on my phenomenon. She’s not truly representative of the values and experiences of the wider trans community.

If you want to thank someone for creating the dialog, thank President Obama. He’s the one that has acknowledged our community on such a high-profile level, especially with the legal status changes enacted during his last term in office. He’s the one that, more than any other actor on the world stage, has upped the ante for the LGBTQ community and driven public awareness and prompted resistive reaction, like investigation and opposition to North Carolina’s HB2.

Some really good work is getting out there now, too. Transamerica definitely depicted a more typical experience for trans women. And Transparent is amazingly sensitive and very well developed regarding the trans experience, down to the details of what might seem like mundane issues such as shopping. It really nails down family dynamics and dysfunction, too, and makes me feel good about the sanity of my own family.

In terms of current trans role models, there are so many great examples living large out there—Laverne Cox, Balian Buschbaum, Candis Cayne, Carmen Carrera, Tiq Milan, Jazz Jennings, Hari Nef, Jennifer Leitham, and many others. I see them as passionately out there doing what I attempt to do, living with integrity and intention. By integrity, I mean that they are living their lives expressing themselves openly and completely as the people they are. By intention, I mean that they are tackling life to make a difference. They are trans people that are out there putting it on the line, taking real risks with their acceptance and safety, making real and lasting changes for their community as well as other communities. If you’re going to give credit to anyone for the trans conversation opening up, give it to President Obama, these rising stars, and all those trans people out there just living their lives.

Speaking of living lives, have you experienced discrimination by the medical community? How would you characterize your interactions and anxiety level in relation to interactions when health is compromised?

S.M.: Not here in the Bay Area. I did have a ski accident in Colorado that required that I go to the medical clinic before being transported to a hospital in Denver. The clinic staff, ambulance driver, and patients openly talked about me. When I got to the hospital I was left unexamined until my family intervened. As a contrast, my appendix burst in San Francisco and I was treated very well.

What challenges do you think lie ahead for the trans community?

S.M.: Trans folk, particularly African American and Latino, or LatinX, and those with fewer resources, remain more vulnerable to violence and abuse. There is a much higher premature death rate among this subgroup. A “Trans Lives Matter” movement is needed really. This is not to say that such an expression should be uttered in response to Black Lives Matter. Politicians and others responding with “All lives matter” or the new police-generated “Blue Lives Matter” legislation shows great insensitivity to the suffering of black people throughout the history of the U.S., which sadly continues today. But a similar inhumanity manifests in response to trans lives that are diminished and destroyed.

I think that we are only in the very early stages of normalizing trans access, rights, and inclusion. President Obama took big steps this year in opening up the military to trans people. Now, for the very long process of cultural acceptance. The Civil Rights Act was enacted into law in the 1960s and we have yet to fully include blacks culturally. Ask me a hundred years from now.

Recommended reading: “SARAH MCBRIDE JUST BECAME THE FIRST OPENLY TRANS PERSON TO SPEAK AT A NATIONAL CONVENTION”

_ _