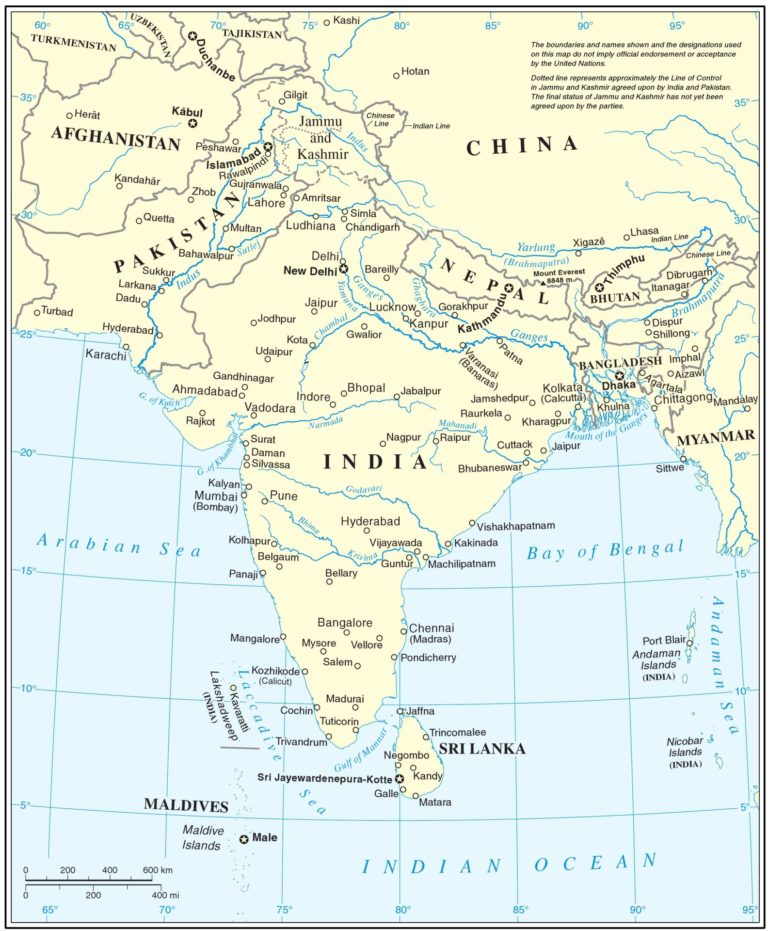

American writer and artist Brian Andreas wrote in one of his stories: “I like geography best… because your mountains & rivers know the secret. Pay no attention to boundaries.” About 263 river basins that connect two or more countries testify to nature’s inattention to states’ physical boundaries in distributing scarce water resources. Transboundary rivers crisscross 148 countries belonging to all continents. South Asia has its fair share of transboundary rivers and aquifers that create interdependencies among its peoples and states. The region is comprised of eight countries (India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Nepal, Bhutan and the Maldives) and inhabited by 1.8 billion people (23 percent of humanity). It falls into the category of ‘high to extremely high’ water-stressed areas, along with Middle-East Asia and Northern Africa. Pakistan and Afghanistan top the list of water-stressed states in South Asia.

Water scarcity in South Asia might seem like an ironic and paradoxical condition as the Himalayan and the Hindu Kush mountain ranges, which divide this region from the rest of Asia, have enormous reservoirs of freshwater. This water flows through twenty major rivers which have sustained the civilizations and economies of South Asian countries over the past millennia. However, the imbalance between water withdrawals and water supply in South Asia during the last few decades is the cumulative outcome of a population surge, high-growth industrialization, rapid urbanization, and a lackadaisical attitude towards environmental concerns.

South Asia is faced with a slew of critical water-related challenges today: severe scarcity of water for drinking and agricultural purposes; uneven access to water between the rich and the poor; disparity in water availability among the various states as well as among the various sub-regions within these states; over-exploitation and fast depletion of groundwater (an estimated 23 million pumps are used to extract groundwater in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal); pollution and contamination of surface water resources and the resulting high incidence of water-borne diseases and deaths; vulnerability to frequent floods and droughts; overuse of water for agricultural purposes; and the potentially dire impactof climate change on the volume and pattern of rainfall, river courses, and sea level.

India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and Afghanistan share twenty major rivers among them.

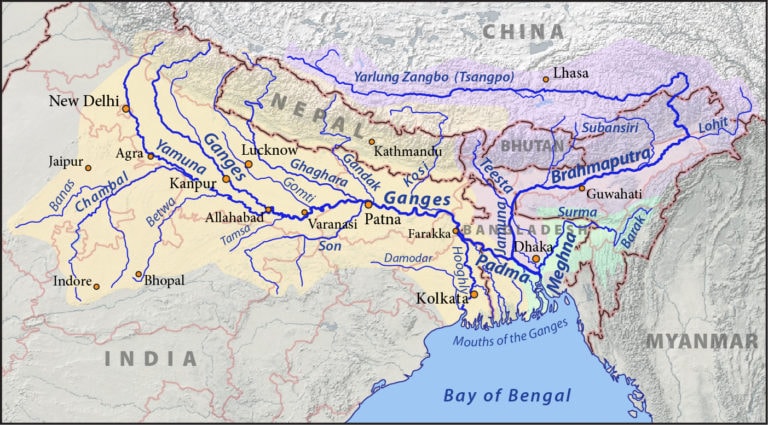

Perennial rivers have shaped the history, politics, culture, and economy of South Asia for several centuries. No wonder that these rivers are considered holy and worshipped by people of all faiths living in the region. They have sustained diverse ecosystems and provided for the livelihood of millions of people. Several of these perennial South Asian rivers have transboundary basins and watercourses. India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and Afghanistan share twenty major rivers among them. The Indus basin (consisting of the Indus, Ravi, Beas, Sutlej, Jhelum and Chenab rivers) inter-links India, Pakistan and China, while the Brahmaputra and the Ganges basins inter-link China with India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan. The Kosi, Gandaki, and Mahakali rivers join Nepal with India. Major rivers shared between India and Bangladesh are the Brahmaputra, Ganges, and Teesta. Pakistan and Afghanistan share the Kabul river basin.

China is a pivotal actor in South Asia’s geopolitics and hydro-diplomacy, since two of the three largest river systems of the region (viz. Indus and Brahmaputra) originate from the Tibetan plateau located in the Southwestern part of China. The region’s third-largest water system, the Ganges, is also connected with the Tibetan plateau. Many of the midstream tributaries of the Ganges originate there even as the main river originates from the Indian side of the Himalayas. As an upstream riparian state, China has a clear advantage in building dams and other infrastructure to reduce or divert water flow from these river systems. Its dam-building and water-diversion projects are already a matter of anxiety for its downstream neighbours.

Shared river basins have triggered several disputes between South Asian states in recent decades. These disputes have aggravated the ongoing tensions in their mutual relations, particularly India-Pakistan and India-China relations. Lack of consensus on principles of fair distribution of river water between upper and lower riparian states, geopolitical tensions caused by the absence of such consensus, and the socio-environmental impact of big dams and hydroelectric power projects have emerged as key challenges of transboundary water management in South Asia.

Either due to international mediation or propelled by intraregional dynamics, India and Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, and India and Nepal have entered into bilateral treaties to create a framework for sharing the water of transboundary rivers. Albeit not without reservations and persistent demands from significant domestic constituencies to repeal or thoroughly revise these treaties. The Indus Water Treaty (1960) specifies the terms of sharing the water of six transboundary rivers between India and Pakistan. The Ganges Treaty (1996) between India and Bangladesh brought an end to their longstanding bilateral dispute. India and Nepal signed treaties in 1954, 1959, and 1996 for water-sharing and project-development concerning the Kosi, Gandaki and Mahakali rivers respectively. Interestingly, there is no formal treaty that regulates the distribution of water from the Kabul river between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

These bilateral treaties are not based on uniform and fair principles; nor are they mutually consistent in their operational terms. As a middle riparian state, India has adopted different upstream and downstream distributive principles depending on the river and the country it is dealing with. Several provisions of these bilateral treaties vary with the accepted international legal instruments, standards, and precedents. This partly explains why no South Asian country has ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourse (1997) which codifies customary international water law to protect, preserve, and manage transboundary water resources effectively, and encourages their equitable and reasonable utilization.

Also, the existing bilateral water treaties are not structured to address the emerging water management chanllenges in South Asia caused by climate change, demographic transition, and technological advances. South Asia can only address these changes effectively by adopting an integrated water management approach at the regional level and multilateral regional agreement. Such an agreement would also help mitigate problems of soil erosion, unsustainable agricultural practices, overexploitation of natural resources, and unfair distribution of water resources.

The enduring tensions in India-Pakistan relations surrounding the intractable issues of Kashmir and cross-border terrorism account for the absence of a comprehensive, multilateral regional agreement on transboundary rivers and aquifers in South Asia. India’s insistence on pursuing a bilateral approach towards its neighbours and its deep aversion to engaging in multilateral diplomacy on South Asian issues is another important reason. Besides, as an upper riparian state and a great power, China has a very little strategic incentive to enter into or push for a multilateral agreement involving its South Asian neighbours, some of whom are too small or highly dependent upon it to influence China’s long-term geopolitical interests.

Even as the probability of a full-fledged multilateral South Asian agreement on integrated water resource management seems remote at this point, small, easy-to-implement steps do look feasible. One possibility is the formation of a working group of ministers belonging to all South Asian states for purposive dialogues on pertinent aspects of trans-boundary water resources and their sustainable use. This working group might involve additional sub-groups of officials and experts to work out common principles as well as specific terms for negotiating the pending bilateral or multilateral problems.

Editor’s Picks — Related Articles:

“Orange County Coastkeeper: Defending Clean Water for 20 Years.”

“Orange County Coastkeeper: Defending Clean Water for 20 Years.”

South Asian countries also need to create and regularly update a regional database of freshwater resources. This would assist in rational policy-making and contingency measures for tackling water scarcity. Most upper riparian states in South Asia tend to suppress the real data on water flows during the lean summer months in order to keep the greater share of river water for themselves (in clear violation of bilateral agreements and international conventions). So all participating South Asian governments must commit themselves to providing credible and transparent data on transboundary river water flows.

There is a vital need for joint action on the impact of climate change factors on the Himalayan ecosystem and glacial reservoirs of freshwater in the region. Such joint action should involve Sri Lanka and the Maldives. As island nations, they are otherwise unconnected with transboundary water management, but confront grave future risks associated with rising sea level. The civil society organizations and international bodies concerned with climate change issues, including the UN agencies, should also get involved.

The alarming rise in the level of pollutants in freshwater resources and the impact of such pollution on agriculture, health, and soil quality requires serious attention from South Asian policy-makers. Agencies, comprised of members from the region’s participating countries, constantly monitoring and improving water quality would lend credibility and strength to individual governments’ initiatives for clean water access. The region’s governments and civil society organizations should implement projects for sensitizing all stake-holders, including common citizens, about grave threats of water stress and climate change looming over South Asia. They should follow sensitization with technical and policy-level capacity development of the identified persons and institutions for the success of regional-level plans.

Legal frameworks determine the norms and functional aspects of managing water resources at the local, national, regional, and global levels. Those frameworks lay down the rights and obligations of contracting parties about their share and use of water. Most significantly, they facilitate environmentally sound decision-making on water issues and participatory, democratic governance of domestic and transboundary water resources. Doubtless, South Asia will increasingly face water-related geostrategic, environmental, political, and social problems, both within and between states. Consequently, tangible steps towards a regional agreement for management of transboundary water resources would prove valuable in achieving the goals of sustainable development, socio-economic justice, and human security in South Asia. Whether the South Asian states would show enough political maturity to set aside their narrow interests at least for this purpose and the well-being of the people and ecosystem of the region is, of course, unknown.