Crafted by men living 250 years ago, when travel and information exchange took great time and effort, the US Constitution drafted by the colonial forefathers, with great skill, overcame deep-seated local differences of thought, economies, and weather — in short, widely differing realities — to find common ground.

In 1786, the infant Confederation of Colonies faced collapse in part due to an outbreak of violence in Massachusetts called Shays’s Rebellion. The Confederation was drifting toward anarchy but was saved almost at the twelfth hour by Alexander Hamilton, whose recommendation that the colonies “call a future Convention which would enlarge the mandate beyond commerce” prevented the breakup into three regional conferences. James Madison put it this way at the time, and his words ring true today:

“We can no longer doubt that the crisis is arrived at which the good people of America are to decide the solemn question, whether they will reap the fruits of that Independence and of that Union … or whether by giving way to unmanly jealousies and prejudices or to partial and transitory interests, they will renounce the auspicious blessings prepared for them…”

They came together, some reluctantly, to sign a document that is our foundational document. It envisioned three equal branches of government, the judicial, legislative, and executive, to serve the public interest. This document resulted in America’s form of government and leadership being widely appreciated and often emulated worldwide.

It is fair to ask whether this is still the case today. Numerous factors, including technological advances, geopolitical shifts, and the widespread influence of social media (much of it false information), have significantly transformed the contemporary world. Much like the Bible, our Constitution has required interpreters to make logistical and moral leaps to address new concerns. If we are honest, this is not working in our present political circumstances. The American people are deeply polarized, and it is hard to see how we can dig ourselves out from the deep chasm between right and left.

Are we heading toward the country’s collapse? Maybe. Could there be ways to find common cause even though one side of the political divide, those who embrace Project 2025, are bent on threatening our governmental system? However difficult, we must seek to find a way to lower the rhetorical and physical threats.

Getting there may mean we won’t succeed until there is sufficient pain from the loss of effective governance for enough Americans to stand up and take back our government, recognizing that some people or parts of the country will suffer from the lack of assistance when others do not.

Related Articles: How America Lost World Leadership | Trump’s Climate Change and Factory Farming Policies: What to Expect From His Win | The Danger Trump Poses to Climate Change — and Our Future | How Trump Was Indicted Again And Why His Supporters Stay Unswayed | Trump at War with Europe | How AI Could Influence US Voters | Can Donald Trump Really Afford to Ignore Climate Change?

Our withdrawal from engagement and withdrawal from international institutions, destruction of federal governmental institutions, damage from the loss of allies, loss of markets, adverse reputational effects of eliminating humanitarian and emergency programs, reversal of efforts to address climate change, and distance from international climate change negotiations will not serve our national interests. As we learned from two world wars in the twentieth century, not seeing the benefits of international engagement will ultimately be more harmful to ourselves.

Some will continue to believe we should no longer want or invest in the imperfect global framework. Americans after World War II worked so hard to build and maintain, including international boundaries of behavior or rules of law. Those people are shortsighted and misguided and, once again, “give way to prejudices, or to partial and transitory interests.”

The need for international interdependence in the twenty-first century becomes clear when seen from the optic of individual health interests. Viruses transmitting infectious diseases do not respect borders, walls, or other national efforts. An epidemic we think is contained in our neighborhood can morph into a pandemic. Avian flu is approaching that point. Not sharing data, surveillance, and containment actions with the World Health Organization and other countries makes us far more vulnerable in our schools and homes. And there are many other risks from the rapidly expanding interface of human, animal, plant, and ecosystem health (One Health), which do or will affect both “them” and “us.” There is much we do not know about emerging health concerns, such as the effects of microplastics and nanoplastics on our health and fertility, which require research and information sharing.

Health is one just example of why we need to look hard at how we adapt at home and abroad to today’s world. Rapid technological advances, multipolar politics, new weapons of war, non-state actors, social media influencers; the list could go on. But, clearly, ours is a very “different” one from that of our forefathers. At home, we need constitutional checks and balances to operate more effectively to prevent/limit executive authoritarian actions, have Congress do its job, objectivity in final judicial decisions, and a body politic that recognizes and accommodates many different legitimate interests. If we do not make our Constitution work more effectively for us, we risk losing a country, pride in a common identity, and allies abroad.

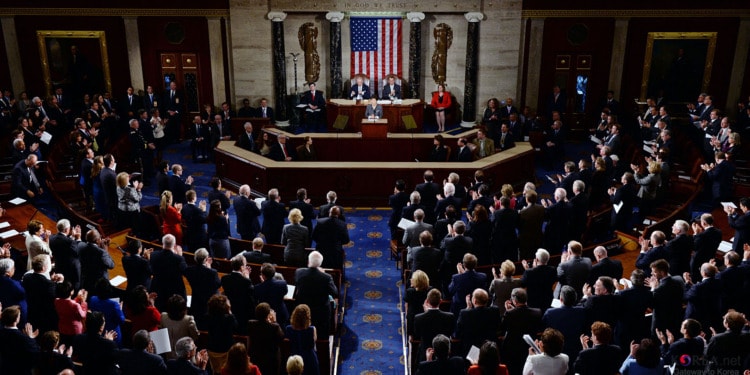

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: Korean President Park Geun-hye (bottom left), US Vice President Joe Biden (top left), and House Speaker John Boehner (right) give a standing ovation to a Korean War veteran family after President Park introduced them on Capitol Hill in Washington, D.C., United States, May 8, 2013. Cover Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.