Seafood is one of the most traded foods in the world, feeding billions of people and supporting millions of jobs. However, beneath the shrimp and salmon on our plates lies a complex system and an often-overlooked climate problem.

From shrimp ponds releasing methane to fishing vessels burning diesel, the global seafood chain quietly emits greenhouse gases that warm the planet. These emissions begin at sea and intensify on land through aquaculture and long supply chains.

At Sea and on Land

While seafood may seem like a natural, sustainable choice, catching it can be surprisingly carbon-intensive as most modern fishing vessels run on diesel. According to the UNCTAD 2023 Review of Maritime Transport, large trawlers and purse seiners can burn up to 1 ton of fuel every 2 tons of catch, releasing large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO₂) and black carbon per trip. Black carbon not only contributes to global warming, but also accelerates melting in polar regions, when it settles on ice.

Bottom trawling, a fishing method that drags heavy nets along the seafloor to catch fish and other marine life, compounds the problem. By ploughing the seafloor, these nets disturb sediment layers and resuspend carbon that has been stored for a long time. Once disturbed, this carbon oxidizes and contributes to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. These direct and indirect effects make wild-capture fisheries a significant contributor to climate change.

Yet, the pollution does not stop at sea. On land, fish and shrimp farming depend heavily on carbon-intensive resources. Industry assessments show that raw material cultivation, processing, and transport are the largest sources of GHG emissions in aquaculture, as fishmeal, soy, and corn all require energy-intensive processes, fertilizer use, and long-distance transport.

According to a 2020 study that quantified GHG emissions from global aquaculture, the production of crop feed materials — including fishmeal production, feed blending, and transport — accounts for 57% of aquaculture’s emissions. Global aquaculture, the study shows, accounted for about 0.49% of anthropogenic GHG emissions, which the authors explain is “similar in magnitude to the emissions from sheep production.”

Furthermore, farms rely on fossil-fuel-powered pumps and aerators while organic waste in low-oxygen ponds decomposes into methane and nitrous oxide — gases far more potent than CO₂. Together, these processes make aquaculture a substantial, often unseen, contributor to global emissions.

The Cost of Keeping Cool

Once caught or harvested, fish and shrimp must be kept cold during processing, freezing, and transport, a system known as the “cold chain.” Refrigerants such as hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) frequently leak from aging systems. Because HFCs have a warming potential thousands of times higher than CO₂, even small leaks can have significant climate impacts.

At the same time, reefer ships burning heavy fuel oil haul frozen cargo across oceans, from farm to consumer, contributing to global shipping emissions. The result is a product that is fresh and local at the table, but carries a heavy carbon footprint.

Beyond Emissions

The environmental damage extends beyond emissions. Overfishing and habitat destruction weaken the ocean carbon cycle. When fish populations decline or seabed habitats are damaged, less carbon is locked away in marine biomass and sediments.

Aquaculture waste flows into nearby waterways, triggering eutrophication: algal blooms that create oxygen-starved dead zones and release more GHGs as organic matter decomposes.

The Climate Feedback Loop

These processes — the release of carbon emissions from fuel use combined with ecosystem degradation and biological waste — form a feedback loop that worsens both climate change and ocean health. As the planet warms, oceans absorb more CO₂, leading to acidification that weakens coral reefs and shell-forming organisms. Warmer seas also hold less oxygen, making marine habitats less resilient to stress.

Addressing these challenges requires more than isolated improvements; it calls for a systemic shift toward sustainable seafood. Reducing fuel use in fisheries, adopting renewable energy in aquaculture, improving feed efficiency, investing in low-emission refrigeration technologies, and restoring blue carbon ecosystems such as mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes, which naturally store carbon and support biodiversity.

Emerging Solutions

Amid these challenges, a quiet wave of innovation is already reshaping the seafood world. From seaweed farmers to electric fishing vessels, scientists, entrepreneurs, and communities are proving that cleaner, smarter ways of working with the ocean are possible — and, importantly, profitable.

Their success stories reveal how sustainable technology and local wisdom can come together to protect both the planet and the livelihoods that depend on it.

Regenerative aquaculture, for example, focuses on rebuilding water quality, enhancing habitat, and cycling nutrients back into productive forms, making farms function more like healthy marine ecosystems. In Indonesia, seaweed farmers are becoming unlikely climate heroes. Seaweed farms require no fertilizers or feed, yet they absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide as they grow.

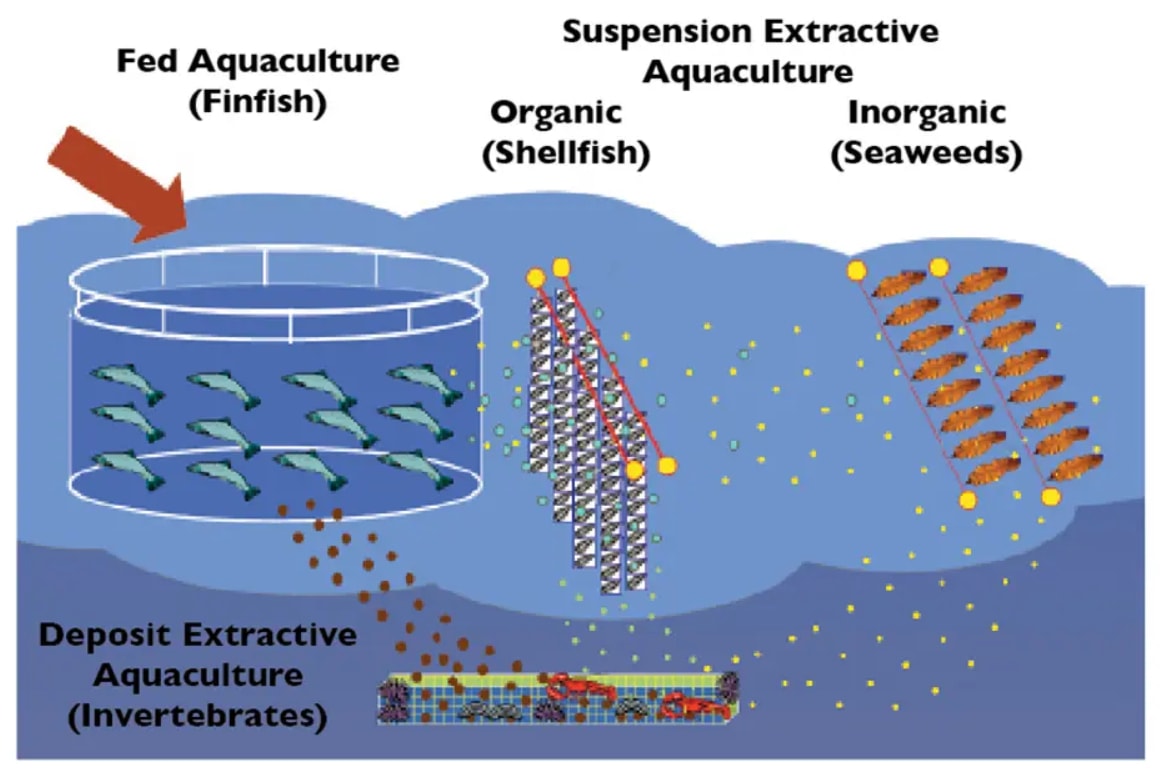

Many Indonesian farmers now practice Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA), a system that grows seaweed alongside fish or shellfish so that each species supports the others. Nutrients from fish waste feed the seaweed, while the seaweed cleans the water and restores balance to coastal ecosystems. IMTA of seaweed (Gracilaria verucosa) and green mussel (Perna viridis) in Java ponds cuts nutrients and organic pollution by up to 67%.

In Norway, electrification of salmon-farm vessels, including battery-powered ships and hybrid service vessels, offers a pathway to reduce GHG emissions. According to the ABB and Bellona report, switching to these low-emissions systems could reduce fuel use and carbon emissions by up to 75%. Electrified vessels also lower emissions of nitrogen oxides and sulfur oxides, improving air quality in coastal regions.

Researchers and engineers are also developing renewable energy systems for aquaculture: solar-powered pumps, wind-driven aerators, and offshore cages that harness tidal energy. At the same time, factories are investing in low-carbon refrigerants, and many processing plants are finding creative ways to use every part of the catch.

According to a World Bank report, about 25% of fishmeal and fish oil production already comes from fish processing waste; however, expanding this practice could increase output and reduce costs. This demonstrates that using by-products instead of letting them go to waste is increasingly feasible and contributes to more sustainable seafood production.

What You Can Do as a Consumer

The ocean can help heal itself. Scientists estimate that blue carbon ecosystems, mangroves, seagrasses, and salt marshes store carbon at rates 40 times faster than forests. These natural carbon sinks also help rebuild biodiversity and protect coasts from storms.

Certification bodies such as the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) and Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) recognize low-impact seafood producers through eco-labels and traceability programs, enabling consumers to make informed, sustainable choices. The ASC certifies aquaculture farms that meet strict environmental and social criteria, including minimizing impacts on local ecosystems, reducing chemical use, and ensuring responsible feed practices.

Similarly, the MSC certifies wild-capture fisheries that are sustainable, well-managed, and accountable, promoting full-chain traceability from the ocean to the consumer’s plate. These certifications empower consumers to make informed purchasing decisions, incentivize producers to adopt sustainable practices, and help drive market demand toward environmentally responsible seafood.

Next time you shop for seafood, look for ASC or MSC labels; your choice can help cool the planet.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Cover Photo: Freshly caught live shrimp and prawns entangled inside a harvesting net on an Indian aquafarm. Matlapalem, Andhra Pradesh, India, 2022. Cover Photo Credit: Shatabdi Chakrabarti / We Animals.