We chose styles that represent the image we want to portray. We align with trends that are shaped by the people we admire. We wear labels that match our lifestyles and aspirations.

Increasingly, the clothes we wear also tell a story about what we believe in.

For the past twenty years, I have been trying to make sure that we can be proud of the clothes we wear. I have lived and traveled across the globe, in places like Bangladesh, Cambodia, Haiti, Jordan, and Vietnam, to make sure that consumers around the world can count on the fact that the women and men who make their clothes are treated with dignity, paid fair wages, and able to work in safe conditions.

Garment factories have long been a breeding ground for human rights abuses. The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York in 1911 killed 143 people. Just over a hundred years later, in 2013, more than 1,100 died in the collapse of the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh. The United Nations agency I work for, the International Labour Organization (ILO), estimates that there are still over 170 million child labourers, many of whom are employed to make textiles and garments.

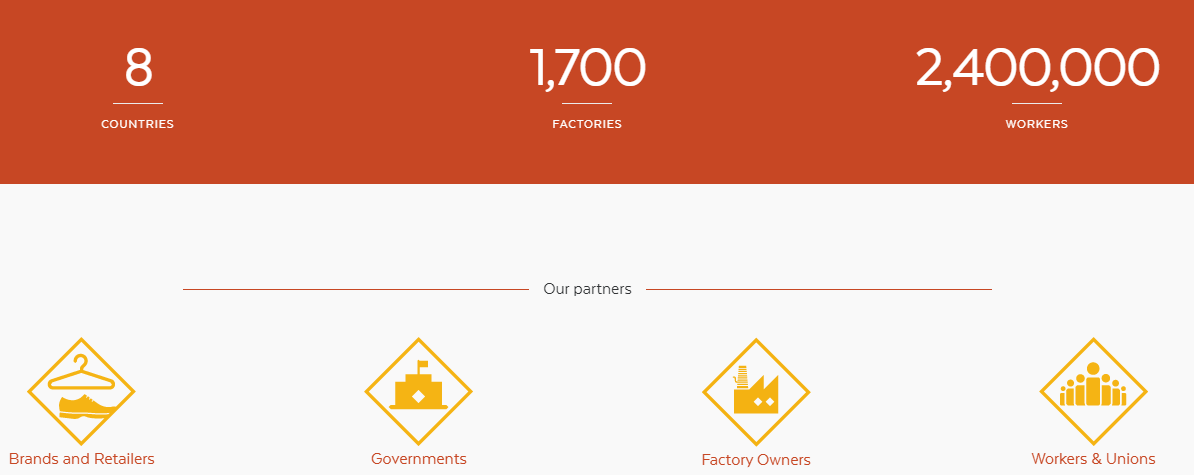

Yet at the same time, the apparel industry provides opportunity and hope. That is what keeps me working in this sector and is precisely what motivates me to keep pushing for change. Evidence from Better Work, one of ILO’s flagship programmes – which I am part of – provides a promising example.

I spent about 5 years living with my family in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. The south-east Asian country has one of the fastest-growing economies in the region. Apparel is one of the key industries that drives that growth, employing millions of workers, many of whom are young women entering the formal economy for the first time. In the 10 years since Better Work came to Vietnam, wages are up, hours are down, employees can raise grievances, and their jobs are safer.

Jordan too, has made significant strides. Factories there, which rely primarily on migrant workers from Asia, were routinely treating their staff as forced labourers, holding their passports and offering them all together worse consideration than their Jordanian counterparts. Today, these individuals get to keep their own passports, their wages have increased, and they have earned the right to bargain collectively with their employers.

All of these countries have something in common; industry leaders decided they had to change the nature of their sector. With the support of the ILO, governments and unions joined forces to modify their approach to ensure their enterprises didn’t fall prey to a race to the bottom.

These are some of the positive trends, but huge hurdles remain.

In most factories around the world, health and safety risks remain significant, working hours are excessive, and wages are often too low to cover basic needs. In Vietnam, 77 percent of the factories we have surveyed do not comply with the monthly limit of 90 hours of overtime, in addition to the normal 60 hour working week.

If you are a shopper, checking you think sustainably is imperative – because you can have an impact on people’s lives. Environmental sustainability is regularly in the headlines and linking this to the human side of the story, by creating quality jobs, is essential. Improving labour standards across global supply chains means safer and better jobs for millions of poor and vulnerable people. It also makes sound business sense, promoting employment growth, economic and social development.

Let’s create a world where the clothes we wear tell a story of empowerment for women, fair wages, safe conditions, and an equal voice for all.

I want my children to choose what they wear not only because of how they look, but also because they know they can be proud of the people who made each item.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. – Photo credit: Clothes factory by Better Work