“Save our Latino children’s potential to contribute to our future” is the key. He started by telling them that there were kids in other parts of the world who could memorize Pi to hundreds of decimal points. They could write symphonies and build robots and airplanes. Most people wouldn’t think that the students at José Urbina López could do those kinds of things. Kids just across the border in Brownsville, Texas, had laptops, high-speed Internet, and tutoring, while in Matamoros the students had intermittent electricity, few computers, limited Internet, and sometimes not enough to eat.

“But you do have one thing that makes you the equal of any kid in the world,” Juárez Correa said. “Potential.”

He looked around the room. “And from now on,” he told them, “we’re going to use that potential to make you the best students in the world.”

–“A Radical Way of Unleashing a Generation of Geniuses,” Joshua Davis, WIRED

The corporate career, where you stay in one place to contribute for a lifetime, has died. Modern work environments embrace individual contributors who work where and when they are needed. They know how to contribute so that they shine and provide the most value. They know what their potential is and how to access it.

My favorite business theorist and futurist, Peter Drucker, anticipated this change:

“Companies today aren’t managing their employees’ careers; knowledge workers must, effectively, be their own chief executive officers. It’s up to you to carve out your place, to know when to change course, and to keep yourself engaged and productive during a work life that may span some 50 years. To do those things well, you’ll need to cultivate a deep understanding of yourself— not only what your strengths and weaknesses are but also how you learn, how you work with others, what your values are, and where you can make the greatest contribution. Because only when you operate from strengths can you achieve true excellence.”

—Managing Oneself, Peter Drucker, Harvard Business Review

To develop ourselves, manage our own careers, and realize our potential, we need a shift in the type of education we are getting. Education needs to move away from being about following orders and focused on memorization – or giving back what is asked. We need individuals and critical thinkers who can lead, contribute, teach others, and teach themselves – as well as learn about who they are in the world.

Sure, we have structures in place like Common Core, which is a great start. But is that enough? We need an education system that can work for everyone. Do we have this in the US? Or is the education system in the US an educational system for a few?

This series will explore what it means for some in the US not to have the same opportunity as others, how some will realize their potential while others will be dismissed based on where they are from, their accents and appearance.

The one unassailable truth from this is; the strength of the beliefs that we espouse create our reality.

— Belief systems as the foundation for our professional evolution, Dr. Greg Dunn, DC* and Dr. Doug Pooley, DC**, The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association

The movie, “Stand and Deliver,” delivers a strong message about education and potential. Based on a true story, the movie tells the story about a math teacher in LA working with the students every day, weekends, and during the summer so they all pass the AP math exam. (They all do.) What does the movie teach us?

- Education transforms how one thinks and acts – both students and teachers. It challenges our beliefs and understanding of ourselves.

- Successful educators are not successful because they have access to money or the kids are from a great neighborhood or have terrific families. Successful educators believe that their students can succeed. Successful educators see the potential in their students and help them achieve.

A class will perform as well as the teacher believes it will perform. And this is dependent on how much confidence a teacher has in his or her students. This is also true for bosses at work and anyone who measures performance.

Generally, if we don’t believe that someone is capable of great things, great things won’t happen.

Our belief system about others can often get in the way of seeing their potential and greatness. We are conscious of some aspects of our belief system and its flaws. We have witnessed injustices, racism, sexism and more in our society and repair these perspectives where we can. But some of our beliefs are unconscious (implicit bias). Implicit bias is probably the most dangerous because we perpetuate injustice unknowingly. It is carried in social myths found in the history we learn, the media’s representation of current events, and perceptions we have of people when we don’t fully understand their backgrounds. One could say that implicit bias in majority culture is a result of understanding what you are told about groups, and not experiencing someone from that group directly.

Latinos who have newly immigrated or are the first generations in the US are one of those groups.

US majority culture and the myths around the value of education in Latin American culture

Often we hear in the news the challenges of Latin American countries and education. Some sample headlines:

- Back to School in the World’s Murder Capital (Education in El Salvador)

- Why Are Mexican Teachers Being Jailed for Protesting Education Reform?

- No Place Is Hopeless: Improving Education in One of the World’s Most Violent Countries

- 800,000 Guatemala youths neither work nor study

- For many children in Guatemala, lessons have to be learned on the street

- Top 4 Reasons Education in Bolivia Lags

- In Latin America, new urgency to educate stirs up outdated system

These are truly educational challenges for areas of Central and South America, in some cases the more rural areas versus the cities. But we must ask: are they problems for ALL of Central and South America? That is one of the challenges with these types of articles and reports. We get a view into only part of the story. But what is the rest of the story?

Roxana Damas, Sr. Managing Director at Diversity RD Global, an expert in Latino, immigration, and diversity issues, told me a different story about education in Central America, specifically, her experience growing up in El Salvador. The school she attended there was quite different than the schools I have seen described.

In most Latin American countries, the teacher at school is the second parent of this child, and he gets all that educational information, follow thru, and coaching mostly inside of the school. Now, [the parents] may hire a tutor from time to time, but you just get everything done within your school.

Photo Credit: Pexels

And from what she described, there is a high standard of discipline at these schools as well. Students wear a uniform and there is a code to follow regarding how students to treat their teachers and each other. Students learn how to honor their word – they do what they say they are going to do, deliver what they say they are doing to deliver.

And attendance was monitored. Students wore a uniform so people knew they belonged in school. There may be two shifts for school, almost like half-day sessions, but few students would skip school because you would be identified as a student and returned.

The responsibility for school children didn’t just lie with the parents. Responsibility rested with the community, which is a completely different experience than what happens in the US, where students skip school and it is up to the parents to find out from the school that the children didn’t show.

(To note, in some cases, parents in Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras did have more parental involvement in schools and it had mixed results.)

Roxana referred to the US experience as US independence. I wanted to explore this further with Roxana, especially since I was born and raised in the US and didn’t fully understand her reference. She explained to me how independent life in the US is a difficult transition for someone coming from a strong community environment. For example, schools in Latin America don’t have a formal structure like a PTA; involvement exists in a more unstructured way. The teacher is part of the community – part of the family – and responsible for the student’s education. And this approach allows all sides – the school, teacher and parent – to better honor each other. In the US, the teacher does teach the student, but it is up to the parent to ensure the quality of a child’s education.

[The parents in El Salvador] don’t understand how you’re not passing a test, and that test is the responsibility of that teacher to be working with you. Yeah, [the parents] support you at home, and they’ll be very harsh for the most part that you are not getting your stuff done.

So the parents care, but in the US, the parents are confused about where their role begins and the teacher’s ends. These roles are very well-defined for them in Central America.

I think stories like Roxana’s and students being accepted to 6 Ivy League universities – another to all 8 Ivy League universities – dismiss the myth that some in US majority culture may have about Latino parents not valuing education. If anything, the challenge many Latino parents have is that they don’t understand how the education system works in the US.

Latinos need a better understanding of US majority culture and education

At times, Latino parents and families don’t completely understand the education system in the US and majority culture – from teacher/parent roles to the school system to advanced education. Roxana further explained to me:

“I think for me there’s this transition that’s kind of missed between the parent, the student, and the school system, and how people are treated or engaged. In some places the school is great and engages the parent very well. The school coaches the parents and families through what their expectations are. However, in some places, people at the front desk [in the school] are making fun of the parent, who only speaks Spanish. One may think that people really cannot tell that they feel disrespected in such cases, but they know. Witnessing this over time, the youth get a very different perspective of authority. And then they don’t really care to respect the teacher, or the parent at some point, because they don’t know who kind of to trust, and follow.”

There is a charter school in San Jose, Downtown College Prep, that focuses its attention on students who are the first to attend college from their families. Some general statistics about the students:

- 96% of their students are Latino

- 90% are low income

- 4% of the parents have a college degree

- 41% have less than a high school education

- 80% performed below grade level when they entered the school

Prisilla Lerza, former Director of Community Engagement and currently a consultant to Downtown College Prep, shared with me in a conversation, the challenges many of these students face in school:

“A lot of our work, outside of academics, is to help students explore their identity — really explore what their interests are and what they might be good at doing. You can teach the students how to choose a college, how to submit an application, and how to write a personal statement. However, if it doesn’t hold any personal meaning for the student, all of that knowledge is sort of a moot point.

Definitely a lot of the work at the middle school level is around community building. There’s a significant interest from middle school teachers around building community and creating a safe space for students in the classroom. There is an emphasis on learning how to push students and challenge them, but also creating a space where students feel free to explore and say, ‘I think I might like that. Let’s do a little bit more work on my math skills,’ or, ‘I need to focus on my reading comprehension or just my plain reading.

At the middle school level, a lot of the work is around just socio-emotional preparation really and engaging students in their education.”

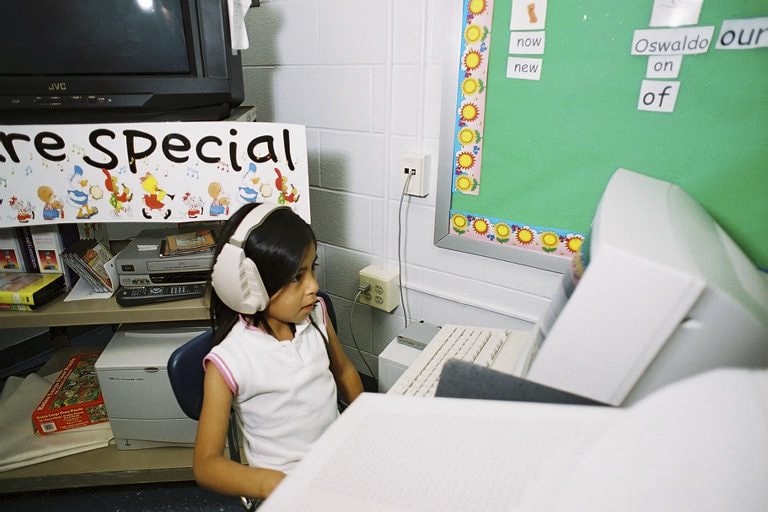

PHOTO CREDIT: CC Flickr/US Department of Education

PHOTO CREDIT: CC Flickr/US Department of Education

This is exactly what Drucker suggested is necessary for someone to function in the work world today. Individuals need to know who they are and how they can best contribute to the world. The students need to understand their potential. It was very encouraging to hear that Downtown College Prep addressed that so early in these students’ development.

Prisilla also shared how she has noticed the students in the school also need to understand US majority culture:

“So one of the things that we try to is to provide is more opportunities while they are in high school, like internships and different things like that where they actually get to be in a more diverse environment.”

Prisilla continued to explain to me that in many Latin American communities there is little interaction with non-Latinos. This can limit a student’s experience – especially if he or she attends college. We discussed her own experience at Stanford after growing up in LA in a predominately African-American community. She was not prepared for Stanford and the white majority culture present. It was a culture shock to say the least.

But for these students to be successful, they need to not only understand where they are going and embrace opportunities to be part of majority culture, but to understand their origins.

“That same high school where we’re doing ethnic studies has a really thriving engineering program right now where 40% of the students are taking at least one engineering course and they’re entering these contests. So that’s the impact, right? It’s that you are instilling in students a sense of confidence that they’re a part of a bigger story and at the same time driving this confidence, creating this safe space, really helps students to explore other interests, which I go back to my story, I didn’t have that so I didn’t feel that sense of safety to pursue my goals.”

But will Latinos understanding US majority culture, building confidence when interacting with it, solve the challenges that they face with the current educational systems? Only if the majority culture in the US shifts its implicit bias against Latinos.

Does US majority culture try to understand Latinos?

I think what bothered me most during my conversation with Roxana was hearing from her the perspective of some American teachers towards Latinos:

“I’ll never forget, someone saying in school, ‘Oh man. Here she comes, again, with these two fat little twins that cannot even read. Are these Mexican women really only good to opening their legs, and they cannot even come and work with their kids at the school?”

Hearing this, and similar stories during our discussion, left me heartbroken. Then I read the book “Women Without Class: Girls, Race, and Identity” and read more about the same expectations on these girls:

“…When I told these teachers that I wanted to talk to some of their girl students about their aspirations beyond high school, teachers shook their heads and laughed together in a knowing way, one man joking that ‘They’ll all be barefoot and pregnant.’ While the other teachers express discomfort with his way of making the point, they did acknowledge that their students did not have high aspirations and often were ‘trouble.”

–Julie Bettie, “Women Without Class: Girls Race and Identity,” p.57

How can a student have a chance to do well if the teacher has no confidence that the student can do the work? Or focus enough during the day to learn and want something more for him or herself? Or the parents can help the student?

If a student and family tries to understand US majority culture while attending a school like Downtown College Prep in San Jose, attitudes like what Roxana describes and worse will prevent them from succeeding because of the implicit bias against them having the opportunity.

The teachers are shutting down the ability to see the potential of their students before the students have a chance to demonstrate the gifts they have.

In the US, we have a number of prejudices about Mexican, Central and South American countries: the gangs, the drug lords, the controversial leaders and dictators, the wars and conflicts, the poverty. And the news that we hear about those countries is constantly paired with negative information so we start to associate those challenges and crimes with Latinos. This bridges into schools and impacts the education of the children.

Similar to African-American children, Latino children arrive at school already facing a barrier defining who they are based on the news and history. Their potential is defined by their origin – and that perception needs to change.

I think what also doesn’t help is our spotty understanding of history in Latin American countries. We hear about the Nazca Lines, Tiahuanaco, and other pre-Incan civilizations. We hold the great civilizations of the Aztecs, Incas and Mayas in high regard, remembering the mathematics, the calendars, and the pyramids. But we also hear about the human sacrifices, the disappearance of the Maya and the Christian invaders bringing religion, “saving” the existing civilizations and people (an embarrassing time of invasion and destruction of people and culture). And as history moves to the present, there are a number of conflicts and regime changes. This shades our perspective of their history to be an unsettled present – and future – with an uncertain and unknown past.

We rarely hear about innovations and inventions in Central and South America or Mexico – like color TV, the birth control pill, the artificial heart and more. Or hear about the accomplishments of the people in business or technology.

For adults to change their perspectives of Latinos and their origins, we need to see more positive perspectives about the culture, its contributions and its achievements. We need to stop continuing the negative perceptions. We need to see promise of what they are capable of doing and have done to know what they can do. We need to be open to see the potential of what Latino students can offer the world.

Photo Credit: Flickr/US Department of Education

Will investing money solve the problem?

Probably not. The problem we have with education isn’t about the money. The problem is a trifecta:

- Respect

- Confidence

- Self-esteem

If some teachers have no confidence that the students can do the work and have little respect for the culture from which the children or parents originate, the students will not have much opportunity. The students already enter a situation with lower self-esteem being new to the culture and with barriers against them based on where they were born or their origins. If there is no respect between the teachers and the students, then the students won’t listen to the teachers and the teachers will disregard what the students have to say.

This is what happens often in education today. And no one wins without respect, listening, and being inclusive.

[Kevin Chavous] believes parents and educators must first recognize and emphasize that all students can learn and thrive in a rich learning environment where high expectations matter and where resources are invested wisely.

— What it Takes to Build a Culture of Learning in America, Gerard Robinson, AEI. ORG

Three Ways to save Latino students’ potential

To gain greater understand for each other – Latino and US residents of majority culture – we need to embrace new ways of interacting with each other.

- Respect. As Roxana pointed out earlier, respect between teachers, students, and parents is key for bridging the gap between cultures. If the teachers respected the students, the students would respect the teachers. This would create a different dynamic than what we often hear about in the schools today. More learning would occur because there would be better discipline. There would be more open minds to understand a different perspective with respect.

- Listening, Understanding and Experiencing Empathy. After talking with Roxana and Prisilla, I learned so much about the other side of the story that we don’t hear about regarding Latino students. If we listened to understand more often, we could build bridges between the communities, teachers and students. And we could build empathy between everyone. You don’t understand what someone is going through unless you have experienced it – or, I would argue, you have truly listened to understand that other person.

- Including. US majority culture needs to be more inclusive in education – embrace Latino history, teach their contributions, and understand their approaches to education, life, and the world.

We need to embrace and understand the contributions of Latinos to the world. Sure, there are areas that could be improved in Mexico, Central and South America, as well as the islands, in education, but what did these areas contribute to the world? What can we learn from these people? How can we bring that pride into US majority culture and embrace Latino culture – not as a side culture, but as part of the US cultural experience?

Let’s return to the WIRED story at the beginning of the article where the teacher decided to build upon his students’ potential. He had confidence in his class and continued to pull out their best. At the end of the year, the kids were tested and:

Paloma [a girl in the article] received the highest math score in the country, but the other students weren’t far behind. Ten got math scores that placed them in the 99.99th percentile. Three of them placed at the same high level in Spanish.

–“A Radical Way of Unleashing a Generation of Geniuses,” Joshua Davis, WIRED

It is only when we embrace, accept, and respect Latino culture then more US students will be able to embrace Drucker’s vision of people managing their own careers, contributing their best, realizing their potential and providing value wherever they go. More of us will be able to be critical thinkers and contribute to society without needing to overcome a barrier based on our origins, appearance, name or language we speak. We need to change and be open to encourage each other to reach our full potential. All of us together.

Recommended reading: “UN WARNS UNIVERSAL EDUCATION GOAL WILL FAIL WITHOUT 69 MILLION NEW TEACHERS“