Editor’s Note: This article is part one of a two-part series by Impakter’s long-term contributor Dr. Festus K. Akinnifesi, Executive Coordinator of Multipartner Initiatives, Resource Mobilization and Private Partnerships Division (PSR) at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Previously FAO’s Chief of South-South Cooperation, Dr. Akinnifesi has over 30 years of experience in sustainable agriculture and food systems. In this first part, he identifies and analyzes major challenges in African agriculture and food systems, proposing solutions that will be elaborated on in the second article.

Most development issues in Africa are fraught with pervasive gaps and extreme inequalities. One such challenge is the generational gap, the variations in how people of different generations view and approach life.

Our value systems and how we respond to given situations are largely influenced by the generation in which we grow up. People born within the same generation tend to share similar values, life views and attributes, which also tend to mirror global events that dominate the era in which they grow up. This can partly explain general differences in knowledge, actions, value systems, degree of opportunities and levels of responsiveness, interconnectedness and technological aptitude. The four notable global generations are generally defined as: (i) The Silent generation (1927–45); (ii) The Baby boomers (1946–64); (iii) The Generation Xers, also known as Baby busters (1965–80); and (iv) The Millennials (1981–96).

Although commonly used as descriptions in western nations, the above classifications have limited application in Africa. Until the late 1950s, most African countries were under colonization: imperialism had a more profound influence and impact on Africa’s generational gaps than World War II. Africa experienced increased struggle for and attainment of independence during 1956–80, with marked differences in how independence was implemented and managed between regions and by the various colonizing nations. Only 7.5% of Africa’s current 53 countries were independent in 1955. A decade later, 67% of them had gained independence, reaching 98% by 1980.

Although commonly used as descriptions in western nations, the above classifications have limited application in Africa. Until the late 1950s, most African countries were under colonization: imperialism had a more profound influence and impact on Africa’s generational gaps than World War II. Africa experienced increased struggle for and attainment of independence during 1956–80, with marked differences in how independence was implemented and managed between regions and by the various colonizing nations. Only 7.5% of Africa’s current 53 countries were independent in 1955. A decade later, 67% of them had gained independence, reaching 98% by 1980.

The generational gaps in the context of sub-Saharan Africa can be aptly described as follows: (i) Pre-independence generation (1942–1961), people born during the colonial era; (ii) Quasi-Independence generation (1962–81), middle-aged people born during the post-colonial era; and (iii) Post-Independence generation (1982–2001), young people born well after independence who have experienced little or no direct colonial influence. These three generations will be hereinafter referred to as Pre-ind, Quasi-ind and Post-ind, for purpose of this article.

Africa’s colonial legacy has enduring influence on its generational gaps. This article highlights the major challenges in the continent’s agriculture and food systems and the potential for harnessing a generational dividend to overcome them.

Demographic shifts and ageing producers

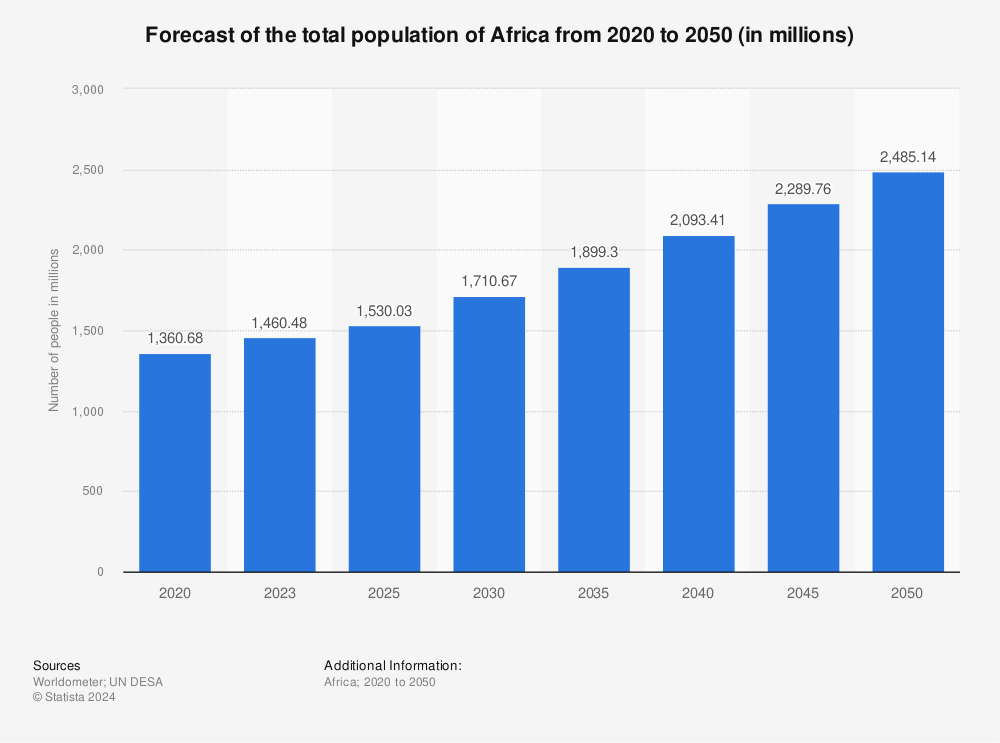

The latest global estimates indicate that at the current rate of 2.7% a year, Africa’s population is projected to double, reaching 2.4 billion by 2050, half of whom will be under 25 years. This suggests that over 122 million young people will enter the labour market in the next five years.

The agricultural sector – which currently employs 54% of people in the informal and formal markets – and food systems will have to respond to this significant change in Africa. This will include addressing the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and worsening food security and livelihood crises, given that even before the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, Africa was not on track to achieve zero hunger.

The continent is thus currently in the midst of two contrasting demographic shifts, facing significant challenges: half of its population is under the age of 15, while 60% are under the age of 25; 65% are aged below 35. Defined as the youth by the Africa Youth Charter of the Africa Union, those aged between 15 and 35 make up 35% of the population. These demographics make Africa the continent with the youngest population in the world. How the youth population can help transform the continent should be among the top priorities for its policy-makers.

Set against Africa’s largely young population is its ageing farming population, widely believed to average 60 years (although recent research suggest the need for more empirical evidence). This projection is worrisome given that only 3% of Africa’s population is aged above 65 according to the World Bank. This implies that most farmers are of the pre-ind generation, and are ageing and dwindling in numbers. Only a small fraction of Africa’s pre-ind population (17%) receive a state or private pension.

This generation will continue to work as long as they can walk, but with limited skills and resources or access to spheres of political influence, they occupy the lower tier of the socio-economic pyramid.

Legacy of disdain for agriculture

Afria’s future lies in the hands of today’s policymakers, but it is Africa’s youth who will bear the consequences.

The quasi-ind generation is also ageing fast, but they still dominate the continent’s middle class. Most of them occupy positions in the national civil service, politics and leadership. This generation sees white-collar jobs or politics as the reliable/predictable route to relative prosperity and success. Their offspring, many with at least secondary school education, have largely shunned agriculture as a career. Although the quasi-ind are nearing retirement age, they have largely no interest in or plans to succeed the pre-ind in agriculture. Africa’s agriculture and food systems sectors therefore face an unprecedented dilemma, a burgeoning labour supply and skill deficits.

Moreover, most African countries lack the level of fiscal income, administrative infrastructure, and perhaps the political will to provide farmers with life insurance, pensions or social protection schemes. Inadequate public healthcare systems and poor nutrition may affect farmers’ productivity. There are also limited incentives for quasi-ind to return to rural areas after retirement, given that at that age they invariably face difficulties in obtaining capital, loans, and entry into the value chain.

Reversing agriculture’s negative stereotypes

In the past, agriculture acquired a negative image due to the hardship of largely manual work, the low returns on labour, and its precariousness. The stereotype, passed on from the pre-ind to the quasi-ind, may have affected the former generation, which mainly sees agriculture through a negative lens.

Such disdain towards agriculture is mainly a legacy of Africa’s colonial past. But the post-ind generation has no recollection of the independence struggles and does not share the nationalistic values of the older generations. Influenced by the appeal of technology and the digital era, they migrate to urban areas and beyond in search of better paying, less arduous, non-agricultural jobs. Thus, policy incentives to attract and retain the post-ind generation in agriculture and food systems are urgently needed, while the challenges facing both quasi–ind and pre-ind generations must be addressed holistically.

Generational targeting of productive resources and social protection

Investment in African agriculture in the past has ignored the evolving demographic changes and the ageing farmers’ population, rendering the agri-food sector increasingly vulnerable. The pre-ind generation mostly bears the burden of producing food for most African nations. They feed the wealthier, stronger, healthier, younger and urban people in society, yet this cohort has rarely received the support and incentives that would allow them to rise above the base of the socio-economic pyramid. It is imperative that today’s engine of the continent’s food basket receives the urgent attention, support and investment it needs to avert an existential crisis.

It is instructive to observe that the modernization of farming that has transformed many other continents has been barely noticeable in Africa, where pre-ind farmers still rely on obsolete tools and manual operations. They have fewer resources, such as land, labour, infrastructure, credit and capacity to innovate at scale. Remedial action calls for a comprehensive, inclusive approach by first identifying factors that can incentivize and increase performance (e.g., linking the pre-ind farmers to the market, offering pensions, insurance, and targeted social protection schemes).

Related Articles: Flexible Pooled Funding Mechanisms Can Drive Transformative Change | The secret recipe for scaling climate-smart agriculture: Youth

The quasi-ind generation is the more successful, and generally dominates the economies across Africa. Nevertheless, few engage in agriculture and food systems. Those who are able to invest more in improved practices have more access to technologies and productive resources. Unfortunately, they invariably lack a generational succession plan and agriculture is generally not their primary focus.

Their knowledge of agriculture is also largely theoretical, thanks to the basic education in agriculture that was often a component of the school curricular up to secondary level. With greater and broader education in agriculture, the few quasi-ind who engage in farming are able to benefit more from technical extension and financial services. However, the quasi-ind generation are unable to take major risks of investing in innovations and modern technologies. As a result, they are unable to maximize value chain and market opportunities.

There is also limited “osmotic” effect between quasi-ind and pre-ind generations in the use of productive resources. Empowering the quasi-ind in innovation would transform the food and agricultural landscape, and could trigger the interest of the post-ind generation. Support to this latter generation should focus on boosting productivity and empowering them with market access, farm insurance, and investment in technological training, innovations and entrepreneurship.

Incentivizing the young generation

Africa’s future lies in the hands of today’s policymakers, but it is Africa’s youth who will bear the consequences. Investing in them and in the agriculture sectors now will yield tremendous dividends. The post-ind generation is more educated, energetic and technologically savvy but is less interested in agriculture. Those who remain in farming consider it a survival strategy and tend to abandon the land and migrate to urban areas. The fragile political economy and inadequate socio-economic conditions constitute a dis-incentive for the pre-ind generation. This has fueled the wave of pre-pandemic migration of the youth, with most taking place, initially, as rural-urban, and intra-continental migration. This has culminated in a skewed labour supply and the increasing feminization and ageing of Africa’s farming population.

Investing in capacity building and creating incentives, and targeting policies to the needs of post-ind generation, could thus change African agriculture’s negative image and perceptions the young people have. Such policies would have to appeal to the youth’s self-esteem and financial ambitions and incentivize their engagement. A key step that would help Africa transform itself into a self-sufficient continent is to integrate entrepreneurship in the school curricular, and re-orient the tertiary education to be more solution-driven.

Going forward, Africa needs to develop a critical mass of post-ind agri-entrepreneurs, who have access to innovation, technologies and productive resources. The post-ind tends to enjoy integrating leisure with work. Making agriculture less labour-intensive and integrating key activities with leisure can yield dividends. Digital innovations in production, marketing, agri-tourism and indoor farming may appeal to the post-ind youth.

Looking to the future

The scale of the dilemma agriculture and food systems in Africa face is significant. Ageing is now the major demographic challenge in rural areas. The pre-ind and quasi-ind are the main operators and managers of agricultural and food systems. They are also conservative and loyal farmers, with limited resources, who see farming as a means for survival – for subsistence – rather than as a business undertaking. The quasi-ind are reluctant farmers and take less risk. Agriculture is less attractive to the younger post-ind generation.

A positive generational shift toward agriculture should thus be a priority for the continent’s policymakers. Bridging generational gaps could help transform agriculture and food systems in Africa. Nevertheless, harnessing generational dividends requires targeted and holistic investment and policies to foster generational succession in agri-food systems within strategies that work for each generation. This should involve a reconstruction of intergenerational succession plans in the agri-food sector, which can happen by making agriculture more attractive to the post-ind through investment in training, infrastructure, technologies, finance and innovation, while supporting both the pre-ind and quasi-ind generations in the transition period with social protection and targeted supports.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Featured Photo Credit: ©FAO.