Editor’s Note: After “War and Peace?”, “Close to the Edge: Climate Change: Focus on Africa, Asia and the Coastal Poor”, “The Fourth Industrial Revolution and the Intelligence Era: What Next?” and “One Health and Wellbeing (OHW) – Inspiring a Global Unity of Purpose”, we are happy to publish the concluding excerpt – focused on our future on this planet – from Dr. George Lueddeke’s highly commended and timely book, Survival: One Health, One Planet, One Future (Routledge, pub. 2019/2020).

This time, Dr. George Lueddeke draws on three main themes not previously highlighted: antimicrobial resistance (AMR), leadership and a potentially dehumanised future.

AMR was selected as it might lead to our next global pandemic; leadership – because malign geopolitical forces (self-interests, power, ambition) continue to threaten the sustainability of the planet; and technological advances (artificial intelligence [AI]) because unrestrained Big Technology could risk the survival of humanity, our species itself.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR): The next ‘supernova in human history’ that could change our future?

The urgency of tackling the basic health infrastructure in existing and emerging cities alongside the shortage of health professionals is made clear by the increasing threat posed by antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to infections – caused mainly by worldwide overuse and misuse of antibiotics or antimicrobials. Exacerbated by the ease of intercontinental travel today, densely populated cities may be most at risk as resistance to first-line drugs to treat infections, such as MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) and tuberculosis (TB), malaria, HIV influenza, to name others, are on the rise.

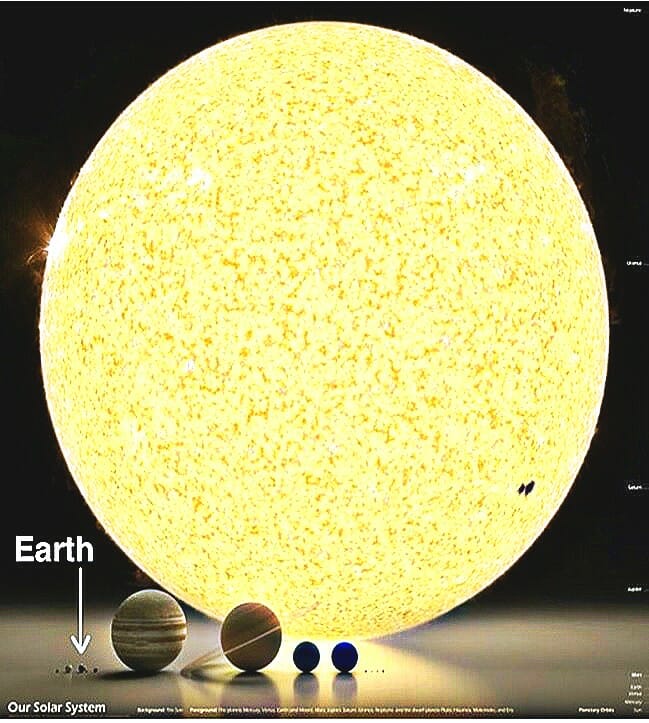

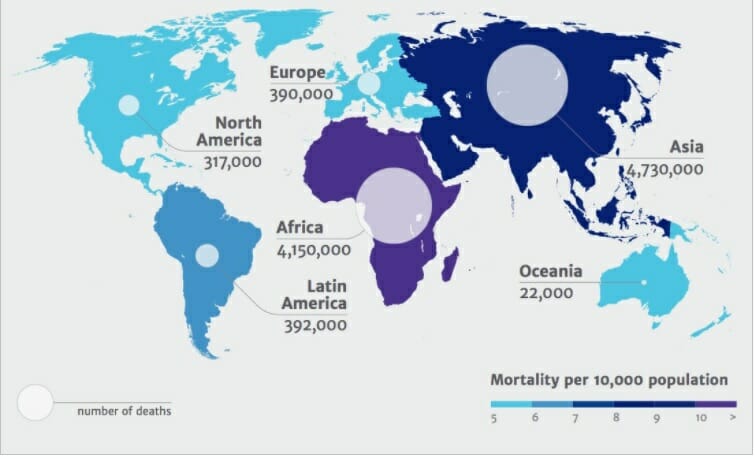

As shown in the figure below, AMR kills about 700,000 people annually with predictions that ‘the number of deaths per year would balloon to 10 million by 2050,’ costing ‘the world up to 100 trillion USD.’ In terms of comparison, ‘that is more than the 8.2 million per year who currently die of cancer and 1.5 million who die of diabetes, combined.’ Most AMR deaths ‘would fall unevenly across the world, with the global south and Asia suffering to a greater extent and losing greater amounts of income. In Africa alone, it is estimated that 25 percent of all deaths in Nigeria could be caused by AMR resistance if trends continue unchecked.’

Deaths attributed to antimicrobial resistance every year to 2050

Following the resolution reached during the sixty-eighth World Health Assembly in May 2015, for Member States to implement a Global Action Plan on AMR, the WHO in collaboration with the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), and World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) released a manual to assist countries to develop or strengthen existing National Action Plans (NAP). Some countries that did not have NAP on AMR like Tanzania have developed and launched their own NAP.

Thinking globally, Jim O’Neill, former Golden Sachs chief economist, was asked to spearhead a mission in 2014 to tackle antimicrobial resistance. Co-sponsored by the UK’s Wellcome Trust and the Department of Health, the independent international review – that drew on eight AMR thematic papers – culminated in a final report with a 10-point action plan.

There can be no doubt that to avoid a return to the ‘dark ages in medicine,’ with ‘more people dying of resistant infections than cancer,’ fundamental change is ‘required in the way that antibiotics are consumed and prescribed, to preserve the usefulness of existing products for longer and to reduce the urgency of discovering new ones.’

As the O’Neill et al. study concludes, accountability for reducing ‘the demand for antimicrobials and in particular antibiotics’ lies with Governments along with the main sectors that drive antibiotic consumption: healthcare systems, the pharmaceutical industry and the farming and food production industry.’

On the other hand, with antimicrobial resistance on the rise and estimates showing that 700,000 to several million deaths result per year, we must all take responsibility for using antibiotics wisely to combat rising drug resistance. Failure to do so is potentially a threat to everyone’s health – humans and animals- and could ultimately lead to societal collapse.

Leading in an Era of Uncertainty, Upheaval and Anxiety

The UN -2030 Transformative Vision commendably calls for ‘ending poverty, hunger, inequality and protecting the Earth’s natural resources by 2030. However, as we are witnessing daily, many parts of the world continue to be in turmoil,’ as the ‘path of escalation and provocation’ continues unabated – despite Western sanctions and televised malign images that are completely incomprehensible as they are deeply reprehensible.

With so much at stake and so few answers to contain strategic geopolitical, economic and military imbalances, we – the United Nations?- might be nearing a historical turning-point where a case for a bolder approach to saving the world from itself is no longer in the realm of “wishful thinking” but has become a matter of necessity – given the state of the planet’s biosphere and civilisation.

With the latter in mind, underpinning the “propositions for sustainability” (see Box 12.1) is the recommendation for a global shift toward a new World Order that would not be distinguished by the continuation of increasingly dangerous West-East, North-South rivalries, threats or power relationships but by ‘the kinds of joint decision-making and collaboration needed to solve the world’s problems’. Our future will depend on it.

In his book, The Age of Uncertainty, economist and author, John Kenneth Galbraith, probably defined the purpose of “leadership” best when he said ‘All of the great leaders have had one characteristic in common: it was the willingness to confront unequivocally the major anxiety of their people in their time. This, and not much else, is the essence of leadership.’

In his book, The Age of Uncertainty, economist and author, John Kenneth Galbraith, probably defined the purpose of “leadership” best when he said ‘All of the great leaders have had one characteristic in common: it was the willingness to confront unequivocally the major anxiety of their people in their time. This, and not much else, is the essence of leadership.’

Another of his quotes, not easily forgotten especially at this time of facing a ‘constellation of unprecedented challenges to peace and security’ relates to weapons of mass destruction (WMD). The stockpiling by at least 9 nations – Britain, China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, and the United States – of ‘lethal arsenals of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons and the materials to produce them’ continues to present a very real danger to the world. Galbraith’s quote should be a wake-up call for all leaders:

‘A nuclear war does not defend a country and it does not defend a system…not even the most accomplished ideologue will be able to tell the difference between the ashes of capitalism and the ashes of communism.’

In light of the potential for nuclear war involving a number of rogue states, it is becoming imperative that approaches other than direct confrontation be found. The University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership study reached similar conclusions emphasising as a top priority the need for ‘the cultivation of a “global” and a “systems” mindset, developing skills of open-mindedness, inclusivity, long-term and systemic thinking, and navigating complexity without trying to artificially reduce it.’

In her informative article on marxism and capitalism, a philosophy professor and research fellow for the UK Centre for Policy Studies, Janet Daley tries to do just that, tracing the steps since the late 1980s to today which have been instrumental in the ‘free movement of global capital and labour’ responsible for transferring ‘power from government to companies.’ Her paper is punctuated with words like ‘revanchist nationalism,’ ‘totalitarian capitalism,’ ‘wealth production,’ ‘technological advances,’ and ‘globalisation- freeing of capital and supposedly, people from national boundaries and local limitations,’ thereby allowing the interests of corporate capital to supersede the power of governments.’

The disruptive effects on the electorate and governments have been substantial, she says, with ‘inchoate rage against “establishment” politicians that are threatening to disrupt the stability and democratic integrity of the West,’ including Italy, Germany, Sweden, the US – all demanding that their own politicians lead them out of this despair’ while ‘In truth, economics is no longer under the control of governments.’

Her plea ‘Somebody, somewhere had better come up with a way out of this, before it becomes irreversible’ might prompt government policy-makers and communities at large to reflect on the mind shift advocated in the “What If” box above.

Former president of the United States, John F Kennedy well recognised the bond that holds the human species together. In his memorable talk at the June 10, 1963 Commencement Address at American University, in Washington, D.C. more than a half-century ago – a few months before his assassination, he pleaded ‘not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women – not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.’

The fundamental importance Kennedy placed on safeguarding our children’s future should continue to be considered the top priority for all global, national and local leaders in this century.

‘So, let us not be blind to our differences–but let us also direct attention to our common interests and to the means by which those differences can be resolved. And if we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity. For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s future. And we are all mortal’….

“As long as poverty, injustice, and gross inequality persist

in our world, none of us can truly rest.”

Nelson Mandela, former president of South Africa

Homo Deus or Homo Humilem? The Choice is Ours

In Sapiens: A History of the Past, author Yuval Harari conjectures that ‘after the 4-billion-year-old regime of natural selection – Homo sapiens in the 21st century are now able to break ‘free of their biologically determined limits’ in which ‘life may be ruled by intelligent design.’

Elaborating this theme in Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow he contends – possibly in line with the late Stephen Hawkins’s prognostications – that during the course of this century technology (non-conscious algorithms) might seek to control humanism (feelings), assisted by ‘genetic engineering, nanotechnology and brain-computer interfaces, ’ – possibly severing ‘the humanist umbilical cord altogether.’

Homo Deus might begin to worship a new ideology, ‘a bolder techno-religion, Dataism, ‘which venerates neither gods nor man – it worships data. ’ This chilling scenario would require replacing the meaning of human experiences ‘inside us’ to ‘infusing the universe with meaning’ because ‘dataists believe that experiences are valueless if they are not shared.’

The battle – humanism vs dataism – which already appears to be in full swing, judging by societal, military and Big Tech developments will essentially be between ‘biologists and the intelligent design movement.’

Initially, Harari observes, Dataism will ‘probably accelerate the humanist pursuit of health, happiness and power – by promising to fulfill these humanist aspirations.’ However, in due course, ’ he speculates, achieving ‘ immortality, bliss and divine powers of creation’ will require processing’ immense amounts of data, far beyond the capacity of the human brain,’ leading to the inevitable conclusion that ‘ the algorithms will do it for us,’ and thereby making ‘the humanist projects’ likely ‘irrelevant.’

Most will find the latter dystopian outcome for humanity philosophically and morally indefensible. However, while the SDGs are leading us in the right direction, they may fall short – not because of a lack of verbal commitment by 193 UN Member States to the goals but because of our restricted worldview – especially not recognizing the potentially devastating impacts – to people and the planet – of creating global divisions, justifying intolerances, valuing virtual over natural realities, including placing data and the sciences over harmonious human interactions, creativity and enjoyment of life.

There is no doubt that in the long run education remains our best defense against intolerance, armed conflicts, corruption, extremism, digital hegemony and misguided decision-making.

However, we should be cautious. Education that treats the arts ‘as inferior’ and pushes students towards pursuing mostly Stem subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) may do society more harm than good in the long run, according to Alice Thomson, a columnist writing from a British perspective….As a result, subjects such as ‘music, art, design, media and drama’ are dropped, forgetting that in future – as is the case already – ‘many jobs that rely on rote learning, formulae, and basic questions will be done by artificial intelligence.’ …‘What makes humans different is the ability to perform intuitive leaps, to collaborate and to create’ through ‘music, art, design, media and drama.’

In a commentary on Alice Thomson’s article, Sir Simon Rattle, music director of the London Symphony Orchestra gave perhaps one of the most cogent arguments why the arts matter while recognising her piece as ‘a call to action,’ saying:

‘…it is essential to the wellbeing and success of our young people that their education prepares them for a future where imagination and creativity are the most important attributes. The future may be uncertain and difficult for the next generation, but unless they have access to a vital cultural education they will be utterly unprepared for what this new world may require. Our children need to have the artistic vitamins that will help to build a better society.’

His insights echo many of the themes in the Development Alternatives report, To choose our future*’, the pioneering work of *Dr. Ashok Khosla, one of the world’s leading experts on sustainable development and chair of the Hydropower Sustainable Assessment Council:

‘We need to refashion our institutional systems and transform our current attitudes to virtually all aspects of society and the economy – consumption patterns and wellbeing, technology and production systems, enterprise and distributive justice – all of which have in the light of today’s circumstances and knowledge need to be reoriented to conform to the principles of an inclusive and circular economy. This implies that the poorest and marginalised are put at the centre of economic and social attention and the restoration and regeneration natural systems become the boundary conditions that must not be transgressed, not just for future generations but also for those of today.’

In his seminal book, Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive, described as ‘an epic journey around the globe, through the history of humanity and on to the future’, UCLA professor Jared Diamond contends, people ‘blame their governments, which they see as responsible for or unable to solve their problems.’

Consequences include conditions that create ‘not only chronic internal conflict, but also emigration of political and economic refugees, and wars between countries arising when authoritarian regimes attack neighboring nations in order to divert popular attention from internal stresses.’ In the extreme, ‘feeling they have nothing to lose,’ some turn to terrorism.

What distinguishes us from the ‘ancient Maya, Anasazi, and Easter Island’ societies, he observes, is that today we are all interconnected and interdependent: what happens in any place on the globe (e.g., social, political, economic, environmental) can have profound repercussions everywhere. For the author, the notion that nations can advance their ‘own self-interests at the expense of others’ or that ‘the elite can remain unaffected by the problems of society around them’ seems both outdated and morally indefensible.

He concludes that societies have two choices that could determine whether they ‘fail or survive’: ‘long-term planning and willingness to reconsider core values.’ For Dr. Alexander Likhotal, past president of Green Cross International and member of the Futures Council, ‘Change is no longer a mere theory, and it is no longer just an option: it is a reality, a “condition sine qua non” of our survival,’ calling for ‘true political leadership, prophetic vision and courage.’

Looking ahead to the remaining decades in this century, we will likely also need to brace ourselves for a world that transcends today’s realities: to make a choice between Homo Deus or Homo Humilem, between ‘highly intelligent algorithms’ (superhuman or artificial?) and a society that truly cares for the ‘sanctity of life’ – humans, animals, plants, the environment – and continues to make life on the planet possible. Our decisions with the former may determine the outcomes of the latter.

Despite considerable pressure from technology giants, military and politicians, the deciding factor could simply come down to our collective ethical resolve not only to stay human but also, as Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chair of the World Economic Forum (WEF) concluded, ‘to become better humans.’

Following his global exhortation, at long last we might finally realise two fundamental truths: first, as the late physicist, Stephen Hawking, “cosmologist’s brightest star,” bluntly put it, ‘We are all different…but we all share the human spirit.’ And, secondly, we might begin to understand the fragility of the planet – and that unless crucial societal transformations occur, including the prevention of ‘nuclear war, global warming and genetically engineered viruses’ – and putting all people and the planet first – the shelf life of Homo sapiens could be extremely short.’

Returning to the book’s Preface, our best hope for averting the possibility of a dehumanising or dystopic world in the 21stcentury – or worse – may lie with recalling the eloquent words of civil rights leader, Martin Luther King Jr (1929-1968):

‘Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.’

Putting Things in Perspective: Adopting a new worldview and holding our species to account

William Joy, an American computer scientist, reminded us several years ago about the need for ‘our species’ to reach global consensus on ‘what we wanted, where we are headed and why.’ In short, on our future on this planet.

Self-interest, power and ambition continue to be the main impediments to adopting a worldview that prioritises the sustainability of life on the planet (shifting from human-centrism [it’s all about us] to eco-centrism, it’s about all species. This mind shift demands recognising the folly of a limitless world and dispelling the thinking that nations can advance their ‘own self-interests at the expense of others’.

Covid-19 has made clear that in order address the unprecedented global challenges we face in the future – climate change, biodiversity loss, emerging infectious diseases – alongside escalating geopolitical threats – we need to reconsider our core values and work together for the common good of the planet.

Education, formal and non-formal, lies at the heart of this transformation ensuring the health and wellbeing of the ecosystems which sustain life on earth while focusing on those in most need and creating a ‘more just, sustainable and peaceful world’. Moving forward demands tackling the lack of willingness to change – particularly calling out those on the world stage who appear determined to pursue a totalitarian ideology favouring chaos over freedoms and disinformation over Truth.

As Sir David Attenborough reminded us, they – and indeed all of us – carry an ‘awesome responsibility…not only our own future, but that of all other living creatures with whom we share the earth.’ In terms of achieving the vision of the UN-2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and as with climate change, there is no Option B.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Protester at a rally against climate change Photo by Ivan Radic