The sixth and current President of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, previously commanded the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). When the former leader, Fred Rwigyema, led the group with a force of over 4,000 into Rwanda in October 1990, Kagame was attending a course at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College (Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, United States). Following the death of Rwigyema on the third day of the clashes between the government forces and the RPF, and the group’s decaying chance of success due to the loss of more than half of the troops, Kagame returned to Africa and took command of the RPF forces. After two months of the regeneration of his soldiers, Kagame restarted the war, which lasted almost four years and finally resulted in the military victory of the RPF in July 1994.

What differed between the RPF led by Kagame and the RPF led by his predecessor? Can we explain the discrepancy between the two practices by relying only on group dynamics or changing circumstances? Or can an individual-level focus provide some fruitful insights?

Individuals cannot be treated as insignificant or passive actors of armed civil conflicts. They, on the contrary, often play a key role in all stages of conflicts by organizing, fighting, manipulating, and most importantly, leading a rebellion. Rebel leaders are not homogenous, and they behave in different ways depending on their motivations and goals. Thus, they should not be treated as though they are all alike. First, they are highly likely to leave their individual stamp on the course of war with their strong preferences and distinctive personalities since they are less likely to be constrained by institutional checks and norms than state leaders. Thus, they are much more autonomous and individually engaged in conflict which makes them appropriate for an individual-level analysis. Even though they are mostly concerned with social pressures, and, as non-state actors, they are limited in their actions due to the limited capabilities they possess, they can still be highly influential actors in many civil wars.

Second, in most cases, rebel leaders are not only the leaders of rebellions, but also the organizers and instigators of them. They play a crucial role in all stages of rebellion seeking to recruit the best participants for their movements, find financial support, attempt to attract attention of third parties to internationalize the conflict if necessary, and, occasionally, target civilians to make an introduction to armed conflict and to demonstrate their ruthlessness as a rebel leader. Therefore, the concept of “rebel leadership” should actually refer to an actor who has a broad sphere of influence within the conflict.

Third, treating rebel groups as social movements, or treating them as if they were states, does not adequately help us to understand how they are organized and they operate. Such approaches may be fruitful for understanding the onset of civil conflict, but a more micro-level context is required to make a full sense of structural organization of rebel groups. And, finally, understanding the behavior of rebel groups vis-a-vis incumbents requires knowledge of the individual-level dynamics underlying the rebel leadership.

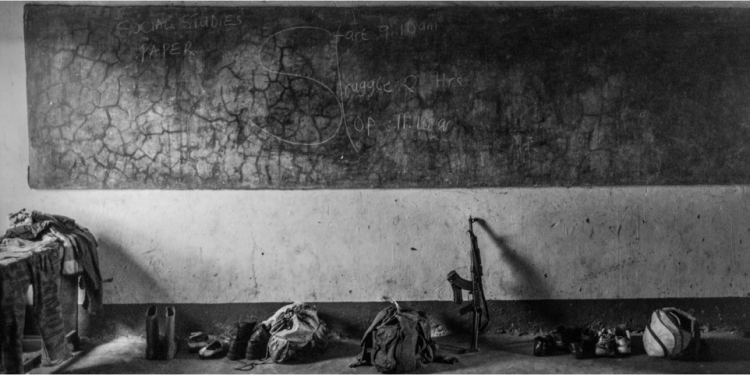

In the photo: Paul Kagame in 1990 leads the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a group of Rwandan exiles—primarily Tutsis—in an invasion of their native country, setting off a civil war Credit: Joel Stettenheim / Corbis

Why should we care about civil wars and rebel leaders, though? The answer is frequency! The United Nations system that was designed to regulate interstate war has been reasonably effective in providing interstate security. Colonial and interstate conflicts, which accounted for half of all armed conflicts early in the post-World War II period, have waned. However, the UN system has failed in regulating civil warfare. Civil wars, especially in the period afterwards the Cold War, have become the predominant political record of the world, while war between nations has become a very rare event. So, in today’s world, whenever we refer to an ongoing war, we are talking about a civil war.

Although decision-making and actions taken during wartime are often shaped and constrained by institutional settings and the conflict environment, the role of individual political leaders has had currency among scholars of international relations. Employing individual leaders as the primary focus of research provides the advantage of a clear emphasize on decision-makers, their individual-level impacts on political phenomena, and their incentives and constrains. However, the major body of the research on civil conflict tend to consider rebel groups as unitary actors. Given the complex nature of rebellion and the pivotal role of leaders in rebel actions, this reductive perspective seems overly simplistic. So, let’s take a brief look at how rebel leaders operate in a civil war and how they can potentially affect the course of conflict.

Most rebel movements lack the necessary economic and military strength to challenge governments effectively. Although diamonds and other lootable resources play a key role in many civil conflicts that motivate the literature (e.g., Angola, Congo, and Sierra Leone), some rebel groups have to organize their rebellion in environments lacking an economic base (e.g., Ethiopia, Uganda, and Rwanda). In these contexts, rebel leaders face the logistical demands of insurgency through means other than the mobilization of material wealth. Then, they have to employ appeals to ethnic or class solidarity, nationalist sentiments, and local social ties to determine the recruits and resources necessary to fight against the governments.

In the photo: Riek Machar, rebel leader of The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (SPLM-IO) sits near his men in a rebel-controlled territory in Jonglei State, South Sudan Credit: Goran Tomasevic, Reuters

The conventional wisdom is that political leaders do what they do to stay in power. They choose and employ policies and strategies that maximize their tenure. This incentive of rebel leaders may look different from the one of state leaders as it is accompanied with the rebel leaders’ desire to gain legitimate political power. Achieving that for a rebel leader, though, still highly depends on his ability to stay in power and achieve the goals of his rebel movement. To put it differently, staying in power for a rebel leader can be considered as a prerequisite of gaining legitimate political power.

Rebel elites generally gain prominence within the rebellion in their leaders’ early tenure. Thus, rebel leaders have to heavily consider keeping their small inner circle of elites (winning coalition) happy and satisfied throughout the war in order to extend their time in power. Rebel leaders can do this in two ways. In conflicts where they fight against resource-rich governments, or where their rebellion is financially supported by a third-party state, they can allow their elites to benefit from the rewards that take place during conflict. Thus, financial rewards may secure the elite support to rebel leaders and help them to get more consolidated in power.

However, most rebel groups are not blessed with economic endowments, and rebel leaders may have to rely on commitments where their ability to provide financial rewards falls short. When rebels can manage at least not to lose–to achieve negotiated settlements or military victory, the post-war order may give the rebel elites significant opportunities for political careers. Hence, when rebel leaders are not able to grant financial rewards to their elites, they tend to “sell the future” to maintain the elite support for their leadership. In these cases, the larger portion of private rewards for the elites is mostly expected to be the loot of victory.

The rebel elites, however, are not enough to win a civil war. Rebel groups have to recruit people to fight. Through a credible claim to control over a specific part of the national territory, rebel leaders provide the potential recruits/subjects future collective benefits as an incentive for support, much as governments do when they provide basic health care, education and infrastructure. Even though insurgent collective action may entail the expectation of future collective benefits, in fact public costs predominate in the short term. In other words, individuals may participate in rebellion not in spite of risk but in order to better manage it.

In this respect, no matter what class of subjects they aim to gratify, aside from the battle-related decisions, rebel leaders regularly engage in a variety of governance activities, including, but not limited to, establishing a system of food production and distribution, fulfilling the health and education needs of the population, providing security from the government violence, allocating resources to bring opportunities to civilians to involve in their livelihood activities, resolving social disputes, and dealing with other social problems.

Among others, one of the most important collective goods that rebel leaders provide is security. In particular, they pledge protection from government forces. Incumbent forces that employ counterinsurgency tactics tend to act brutally, employing tactics that may target and victimize civilians indiscriminately in an effort to eradicate the support base for rebel movements. Such indiscriminate violence can drive individuals into the waiting arms of rebel leaders, especially when their groups are capable of mobilizing armed forces to protect civilians from further violence of the government. The historical record reveals that extreme levels of state violence often leave noncombatants no other option than to join the insurgents.

By engaging in the governance activities mentioned above, rebel leaders try to overcome a very common problem: collective action. The most widely recognized explanation for why some rebel leaders manage to solve the collective action problem is that political change will generate private benefits for the leaders and their followers. Leading political analysts and scholars of civil conflict suggest that looting rebellions are exempt from intrinsic collective action problems since the activity is privately profitable. Justice rebellions, on the other hand, are likely to have acute problems in collective action. They specifically note that looting-centered insurgencies, unlike those that seek justice, need not defeat a government because their goal is achieved as long as they can keep stealing from the local population and exploiting mineral resources that they have seized.

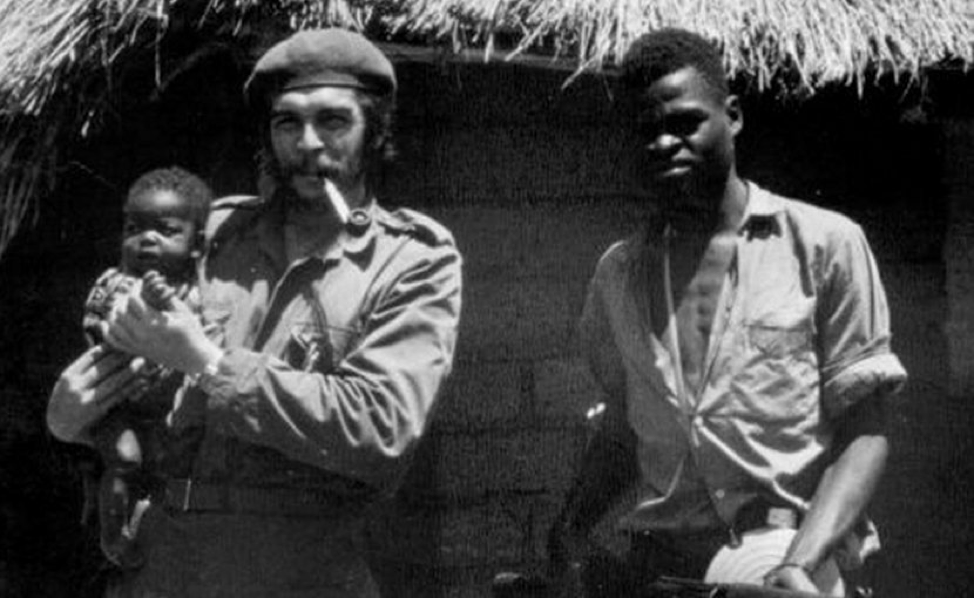

In the photo: Che Guevara in the Congo, 1965 Credit: Wikimedia commons

David Keen (in The Economic Functions of Violence in Civil Wars, 1998) points out that “ideologically motivated rebel leaders–e.g. Mao Zedong and Che Guevara, banned economic violence among their forces and obtained highly disciplined rebel movements as a result.” Nevertheless, Keen adds that, especially in the post-cold war era, civil conflict has increasingly become the continuation of economics by other means as insurgencies are no longer anticolonial-oriented and it has become much harder than before for rebels to get foreign support. Consequently, rebels have to depend financially on the land and sometimes become over-dependent to looting.

Civil conflicts are complex and ambiguous phenomena that disable scholarly efforts that choose to investigate them along a single dimension. This complicated nature of the concept, instead, blurs our understanding of even the most straightforward conflict. Consequently, the question of rebel behavior does not indulge to mono-causal explanations or overly simple dichotomous formulations. As an alternative approach, it seems plausible to think about contemporary rebel leaders as involving in a series of interactions with a variety of political and economic actors and influencing all stages of civil war. Despite the fact that it is impossible to identify all key challenges that influence the development of rebel governance of rebel leaders with a single catch-all variable, a leader-level concentration in the study of conflict still promises an outstanding potential for development.

Editors Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com