The WorldBank’s recently released Atlas of Sustainable Development Goals 2018 reminds us how hard it is to measure what matters most to SDG 4 – quality education. Atlas’ indicators depict consumption, conditions, and consequences of education, but not its quality. The missing data on quality, lamented in the WorldBank’s 2018 World Development Report Learning to Realize Education’s Promise, severely constrain the reform conversation and, by failing to reveal the problem, perpetuate low quality. Even so, the Atlas presents several compelling data visualizations which unmask inequities faced by pupils in low-income countries.

Consumption – Children in low-income countries start school later and stop attending sooner.

Primary school attendance is not the problem. Most children throughout the world attend primary school. Before and after primary school, however, the picture is dramatically different in low-income countries, where fewer children receive early education and where less than half complete secondary school. Within the regions we serve at Bridge, especially Kenya and Nigeria, there are too few secondary schools to accommodate eligible pupils.

Additionally, secondary school fees often greatly exceed primary school fees, requiring additional financial investment from families and disproportionately excluding the lowest income families from secondary schooling.

In low income countries, enrollment patterns for early education are even bleaker for those for secondary education; Only one in five children attends pre-primary education.

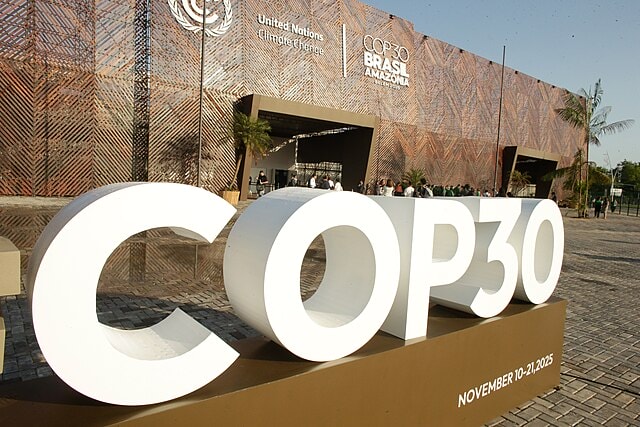

In the photo: Pupils in the classroom. Credit: Bridge International

Conditions – Classrooms are crowded. Schools are often missing drinking water, lack electricity, and fail to provide single-sex toilets.

Enough said.

Consequences – Life is better for those who go to school longer.

In low-income countries, female secondary enrollment has doubled since 1990. During this period the adolescent fertility rate for girls has dropped by 25 percent. Even so, in these countries, female school enrollment and completion lag behind male enrollment at all levels, with the disparity increasing for secondary, and even more for tertiary schooling. In higher-income countries, these gaps have disappeared or even reversed.

It is good to be able to describe how pupils’ educational experiences differ by the income-level of the country. Doing so adds detail to our understanding of the inequities that add to the struggle of citizens in low-income countries to improve their lot.

The contrast between pupils’ experience of education in high and low-income countries reminds us that educational outcomes are driven by much more than ability.

It also suggests the tremendous waste in human potential unrealized when pupils in low-income countries receive less education as a consequence of their birthplace.

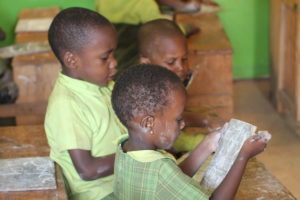

In the photo: Pupils in the classroom. Credit: Bridge International

Quality – We need to invest in measuring what matters most.

Still, quality matters. A lot. While we lack anything approaching universal measures of quality across most low-income countries, several high-quality studies have revealed striking performance differences among schools within a country. In one such study, pupils at Bridge Partnership Schools for Liberia, fee-free public schools, learned twice as much as a randomly selected comparison group of traditional public schools in Liberia. Differences like these suggest that some of the answers for what constitutes effective schooling likely already exist and can be found within schools currently in place. The problem is that we don’t have a systematic way to identify such schools and to learn from them.

The field is recognising this, and initiatives such as the Education Commission’s challenge to fund the Learning Generation are poised to invest in bringing educational outcomes into the light. We’re grateful for the 2018 World Bank’s SDG Atlas and hopeful that its next publication will be even more helpful to those who lead and support education in low-income countries.