Data collected through computers, smartphones, and other devices play a critical role in today’s society. On one hand, data, including those gleaned from your search history, cookies, or auto-complete forms, are helpful to facilitate the use of devices connected to the Internet. They know what we frequently search and thus facilitate our user experience. On the other hand, devices often collect, through apps, an uncomfortable amount of personal information and data about us and make it available to app developers or tech companies putting users’ privacy at risk.

Data could be used directly by the company that collects them, or they might be sold to a third-party company. In both cases, if the company that has collected data has a headquarters or a data storage facility located in another country, data must be transferred.

This is what is known as data transfer: the process wherein our personal data are most at risk.

Photo Credit: Flickr/FutUndBeidl

The inherent danger of this process lies in the potential for data leaks, as well as the question of which laws protect our data during the process. For example, if data are collected from the European operations of a US company, which law applies to the matter of privacy when transferred to the USA?

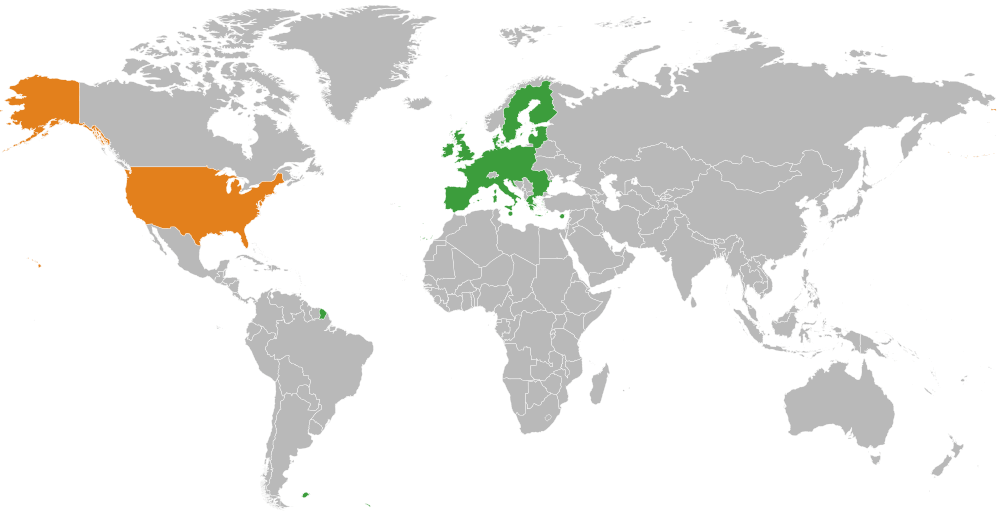

The issue of data transfer from the EU to the US has been under discussion since the exponential development of the Internet in Europe at the turn of this century. European and US legislators have adopted distinct approaches towards this topic. The European approach prefers to set rules first and force companies to respect them. Europe’s first regulatory structure to govern data protection is the Data Protection Directive of 1998. The US approach towards privacy is much more laissez-faire, allowing companies largely to self-regulate and build their own privacy policy, while ensuring that general principles of US law are respected.

How could these two completely different approaches towards data privacy policy possibly work together? How could US companies be encouraged to respect European principles given the fact that data transfer from Europe would not be allowed to countries that do not respect the principles of the Data Protection Directive?

The answer is what was known as the Safe Harbor Agreement.

The Safe Harbor Agreement

The European Union and Switzerland signed the Safe Harbor agreement with the US in 2000. This agreement was the result of a long and difficult policymaking process that involved the US Department of Commerce and the Data Protection Commissioners of the European Union and Switzerland. The aim of the agreement was to regulate data transfer across the Atlantic and build up the emerging Internet-based economy. The process of data transfer and storage in the US had to follow seven principles:

- Notify individuals about the collection of their personal data.

- Give them choices regarding certain uses of their personal data.

- Ensure the accuracy and integrity of their personal data.

- Allow access and, if necessary, correction of their personal data.

- Protect the security of the personal data.

- Comply with restrictions on further transfers of the personal data.

- Provide an independent dispute resolution mechanism for privacy complaints concerning European personal data that they collect, receive or process.

All US companies involved in the data transfer process would have had to respect those seven principles and self-certify the fact they were actually complying with them. More than 7,000 companies were party to the Safe Harbor agreement, including Google, Facebook, and Amazon.

Related article:

“YOUR ONLINE REPUTATION—CAN WE REMOVE INFORMATION WE DON’T WANT TO SEE ABOUT OURSELVES ONLINE?”

The Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) on Safe Harbor

On October 6, 2015, Europe’s highest court, the European Court of Justice, declared the Safe Harbor Agreement to be invalid. This means that data transferred could be taken and used by other third-party authorities, like an intelligence agency, without requiring the third party to respect the seven principles of Safe Harbor; as such, the Safe Harbor agreement had to be declared invalid, establishing a need for a higher level of protection.

Who helped to bring about the downfall of Safe Harbor? Two names: Max Schrems, an Austrian privacy activist and, indirectly, NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, who first revealed to the public the extent of the surveillance activities of US and British intelligence agencies. Schrems filed a complaint against Facebook to the Irish Data Protection Commissioner. When the Irish Commissioner rejected the complaint, he made a reference to the Snowden case in his judgment. He mentioned also the surveillance activity of US intelligence agencies. This opened the door for Schrems’ complaint to the CJEU which ultimately ruled that Safe Harbor be declared invalid.

Internet giants such as Facebook and Google claimed that they were not affected by the end of Safe Harbor as they have other clauses and binding corporate rules to regulate data transfer. However, those clauses and binding corporate rules could be subject to legal action from any European citizen in front of their local Data Protection commissioner. It is what is starting to happen in several European countries. In Belgium, the Data Protection officer is trying to stop Facebook from collecting data of individuals who are actually not even a member of the social network.

The Privacy Shield agreement

The direct consequence of the decision of the CJEU on Safe Harbor was an attempt to have a new agreement, first named Safe Harbor 2.0, and later renamed Privacy Shield, that forces US companies to embrace stronger obligations to protect Europeans’ personal data, and companies must subsequently publish their “commitments” to data protection.

The US Department of Commerce and Federal Trade Commission will have to engage a “stronger monitoring and enforcement” of companies’ data protection practices. The US has provided written assurances that the ability of national security and law enforcement authorities to access personal data “will be subject to clear limitations, safeguards, and oversight mechanisms”, and that the US government will not engage in the unwarranted mass surveillance of personal data transferred to the US under the Privacy Shield arrangement. This was a significant concern for the EU, given the decision of the CJEU.

Anyone who feels that their personal data has been misused under the Privacy Shield program will be given the opportunity for redress. Europeans will also be able to contact an ombudsperson with any complaints about potential data misuse; the US will decide who will be the ombudsperson at a later date. The EU and US will engage in an annual joint review in order to assess the implementation of these measures.

The draft of the agreement was ready to be ratified by the European Commission, the European Parliament, and individual European countries, but there was a complex pre-ratification process, including a check from the European ombudsman before final implementation. The Article 29 Working Party, the EU’s foremost authority on privacy, stated in April 2016 that the new agreement was a significant step forward. However, the group still had significant concerns about “the independence and effectiveness” of the relevant ombudsperson who would ultimately manage European complaints over NSA data use.

Unfortunately, however, European data protection authorities (DPAs) and European Data Protection Supervisor Giovanni Buttarelli asserted that the protection granted by the Privacy Shield was still not enough. It is still possible that the CJEU will eventually dismiss the Privacy Shield Agreement as well, not granting enough protection against data leaks. Buttarelli claimed that the level of protection granted by the Privacy Shield is better compared to the Safe Harbor, but Safe Harbor shouldn’t be used as the reference point for future privacy legislation. The Privacy Shield should only be read and compared to the general European principles on data protection.

The statement from Buttarelli and the European DPAs came a few days before the European Parliament passed a resolution to renegotiate the terms of the Privacy Shield agreement. The Article 29 Working Party will work together with the Article 31 Committee (the designated authority to make an agreement with US counterparts) to find an agreement which will ultimately satisfy all European requirements for safe data transfer.

European concerns over privacy are quite high, especially in the face of US tech companies. Europeans are also concerned about the idea that their information could be later shared with intelligence agencies. The Snowden case has shown that no matter the type of agreement that has been arranged, it is hard to prevent the leak of information.

The debate remains fierce. There lies the desire for privacy and data protection; simultaneously lies a growing need for security through surveillance, purportedly required to prevent terrorism or other crimes.

In The Photo The EU and The US. Photo Credit: Wikipedia/ Ssolberj

However, not everyone views it in this way. According to some in the US, European governments are using privacy as a weapon against tech companies to punish or force major US companies to invest, pay taxes, or undertake operations in their home countries. All European countries are trying constantly to drag US tech giants to have their headquarters in their countries. If they cannot reach an agreement, this could be another way to obtain it.

While the discussion on Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership agreements continues between the EU and the US, an agreement on similar principles and standards for data privacy may need to be set in place in the near future. Higher and similar standards between the US and the EU should be recommended, though this remains difficult due to the very distinct attitudes between the US and the EU towards privacy. A European standard that would still allow European companies to be competitive with US counterparts in the tech market would be the ideal solution. A stronger US standard that would still allow US companies to make profits with data without sharing and/or misusing them with third parties would be ideal on the other side of the Atlantic.

Recommended reading: “APPLE’S DIFFERENTIAL PRIVACY ALGORITHM WILL REQUIRE YOU TO OPT-IN”

—

EDITOR’S NOTE: THE OPINIONS EXPRESSED HERE BY IMPAKTER.COM COLUMNISTS ARE THEIR OWN, NOT THOSE OF IMPAKTER.COM.