Editor’s Note: Building on previous publications, George Lueddeke PhD, independent Global Lead of the international One Health for One Planet Education initiative, focuses on several key themes in this new article, including Democracy vs Autocracy, the Russia-Ukraine War, climate change and environmental degradation along with the global challenge to shift our priorities from human-centrism to eco-centrism. Drawing conclusions from global risks and mitigation efforts to counter these (eg. COP27), the author questions the extent to which decision-making bodies are ‘fit for purpose’ and argues that the only way forward is through transforming human behaviour and giving voice to all stakeholders, in particular youth.

In his concluding comments, he cites Nobel Laureate Professor Douglass North who observed that “societies that ‘get stuck’ embody belief systems (mental models) and institutions that fail to confront and solve new problems of societal complexity.” The overall purpose of the article is to raise awareness of the need to adopt a new worldview that ensures human needs are compatible with those of all other species and that supports restoring and regenerating ecosystems to optimise planet sustainability.

Values and responsibility: connecting the dots

In Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive (2005), Professor Jared Diamond concluded that societies had two main choices: ‘long-term planning and willingness to reconsider core values,” reminding us of the folly that we live in a limitless world and that leaders can advance their “own self-interests at the expense of others.”

The main difference between now and then, he highlighted, was that unlike the “ancient Maya, Anasazi, and Easter Island” societies today, and the UN-2030 Sustainable Development Goals have underscored, we are all interconnected and interdependent: “what happens in any place on the globe can have profound repercussions everywhere.”

Climate change, nuclear weapons, pandemics, and rogue artificial intelligence stand out as key existential threats facing us, prompting the urgency of addressing root causes and mitigating these before we do reach ‘a point of no return.’

One statistic seems especially significant and should make us stop and think: According to World Wildlife Federation International (WWF) in its latest report (October 2022), “The population size of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles have seen an alarming average drop of 69% since 1970” with a “staggering 94 percent decline” in South America and the Caribbean, the highest in the world.

As the WWF cautioned in a previous Living Planet Report (2014), “These are the living forms that constitute the fabric of the ecosystems which sustain life on earth and the barometer of what we are doing to our planet, our only home.”

We are now in the earth’s sixth’s mass extinction phase. The last one, caused by an asteroid, wiped out the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. We may be becoming that ‘asteroid’ as well-known naturalist and broadcaster Sir David Attenborough starkly reminds us:

“The fact is that no species has ever had such wholesale control over everything on earth, living or dead, as we now have. That lies upon us, whether we like it or not, an awesome responsibility. In our hands now lies not only our own future, but that of all other living creatures with whom we share the earth.

Democracy on the brink

History tells us that the human race is highly vulnerable to exploitation and profiteering of others often motivated by vested interests, ambition, and power. At the state level, these personality traits can translate into nations evolving or turning into autocracies generally defined as “a form of government in which a country is ruled by a person or group with total power.”

In the past ten years, this form of government has been on the rise whereas the number of democracies, “a way of governing which depends on the will of the people, ” has declined.

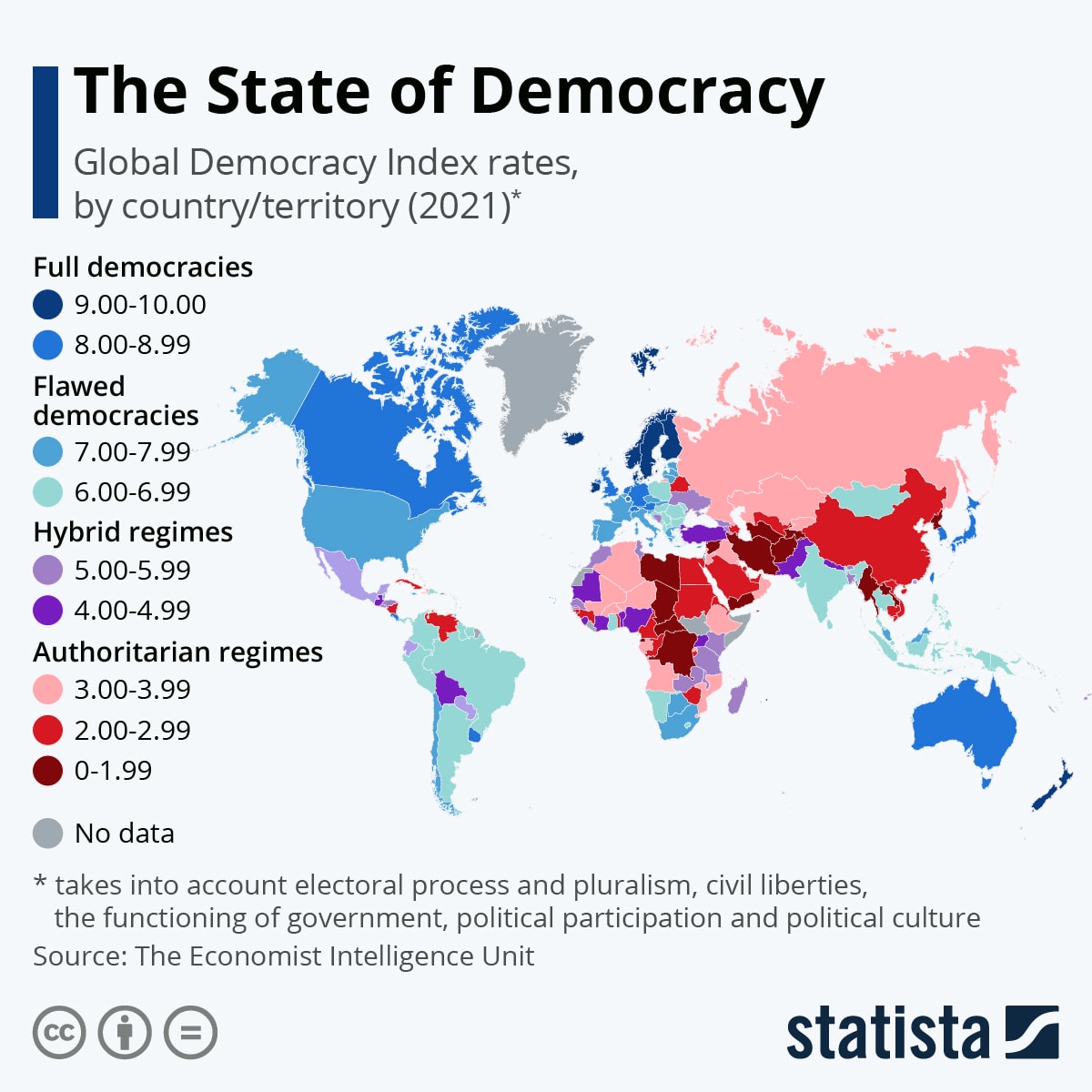

According to the Economics Intelligence Unit (EIU) annual Democratic Index 2021, “less than half the world’s population (45.7 % of 167 countries) now live in a democracy of some sort which is a significant decline from 2020 (49.4%). Even fewer (6.4%) reside in a “full democracy. Substantially more than a third of the world’s population (37.1%) live under authoritarian rule, a large share of which are in China.” (bolding added)

Democracy vs autocracy

In How Democracy Can Defeat Autocracy, Kenneth Roth, former executive director of Human Rights Watch, reviews autocracies across the globe and highlights how its advocates deny “not only periodic elections but also free public debate, a healthy civil society, competitive political parties, and an independent judiciary capable of defending individual rights and holding officials accountable.”

Although autocracies are on the rise, he cautions that their “superficial appeal…belies a more complex reality—and a bleaker future for autocrats”: people are increasingly recognising that “autocrats prioritize their own interests over the public’s,” regularly devoting “government resources to self-serving projects rather than public needs.”

For democracies “to prevail”, he opines, “leaders must do more than spotlight the autocrats’ shortcomings” and “make a stronger, positive case for democratic rule” to meet “national and global challenges—of ensuring that democracy delivers on its promised dividends.”

The main problem in delivering societal expectations whether “climate change, the pandemic, poverty and inequality, racial injustice, or the threats posed by major technology companies,” Roth asserts, is that they “are often too mired in partisan battles and short-term preoccupations to address these problems effectively.”

However, a different story may be unfolding in the US as those responsible for the January 6, 2021, insurrection are beginning to disprove Roth’s assumption as high-level government officials and rebellion leaders are brought to justice.

The outcomes differ markedly from what is happening in surveillance state China where efforts to democratise society are immediately and brutally thwarted. It remains to be seen how the present situation plays out across China – and its impact on the world – as the scale of the Covid lockdown protests becomes clearer.

According to a recent analysis, the question is which of the three main factions in the Communist Party will predominate – the ‘left,’ ‘centrists’ or ‘liberals’? The latter group includes “students, workers, doctors on the streets,” and, “for the first time, people in the higher party echelons who support them.”

The future of democracy

While there is considerable evidence that democracies function better than autocracies and that people are beginning to see the benefits, there are also potential threats.

In his commentary, AI will shift power toward the autocrats, James Marriot, staff writer at The Times, acknowledges that although democracy has had a good year with election outcomes in the US and Brazil, he detects “a mood of premature celebration.”

Entering “the harsher environment of the 21st century,” Marriot’s main fears are that technology is weakening “the openness to new ideas” and creating “an impoverished middle class”- the “surest route to revolution.”

The Russia-Ukraine war

Possibly also facing a crunch moment in Russia is Vladimir Putin. In a wide-ranging interview, futurologist and author of Sapiens Yuval Noah Harari brought a sense of realpolitik to the situation unfolding in Ukraine saying, “If Putin is allowed to win then this will become the new normal. Governments all over the world might invade their neighbours. It becomes ‘a turning point’ in world history. The global order of the late 20th century and early 21st century is over, and we are back in the jungle.”

In a speech to the Munich Security Conference entitled ‘The Lessons of History,’ a few days before the start of war, President Volodymyr Zelensky raised similar concerns asking attendees, “Has the world forgotten the mistakes made in the 20th century? How did it happen that in the 21st century, Europe is again at war and people are dying? How is it that this conflict has lasted longer [since the 2014 annexation of Crimea] than the Second World War?”

For President Zelensky “The rules that the world agreed upon decades ago no longer work…They offer a cough syrup when what you need is a Covid vaccine.” With over 200,000 lives lost on both sides in just 11 months, his impatience with many world leaders was palatable insisting that the “architecture of world security is fragile and needs to be updated.”

A major stumbling block reported in an opinion piece entitled, This is how Vladimir Putin’s dismal rule ends, is that “Russia holds one of the five permanent seats on the United Nations Security Council” and along with China “can veto any move by the West to establish a war crimes tribunal,” assuming “that the UN is the only organisation that can oversee such matters.”

However, author Con Coughlin, Defence Editor at The Telegraph counters this premise noting that in the 1990s several “key perpetrators” of atrocities” were “arraigned on war crimes charges before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yuguslavia” and investigations are ongoing today “examining Syria’s recent civil war” and “war crimes.”

UN Conference of the Parties (COP27): “Our planet is still in the emergency room!”

UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres voiced his deep frustration lamenting that “our planet is still in the emergency room,” and calling “for an end to “our addiction to fossil fuels.”

Concerns about decision-making processes that are “fit for purpose” also emerged from the recent COP27 summit in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

While some progress was made by rich countries agreeing to compensate poor nations for the damage inflicted by their CO 2 emissions, the summit failed to persuade governments, corporations and lobbyists to tackle the main reasons for the rise in global temperatures and agreeing multilateral steps forward to mitigating these.

The fossil fuel industry was well represented at the summit, acknowledged by Laurence Tubian, a former French diplomat and an architect of the 2015 Paris agreement who observed that “the fossil lobby’s fingerprints were everywhere in the final deal” with “language on shifting to renewable energy “weakened in the final minutes.”

In this regard, it was revealing that an India-supported proposal to “phase down all fossil fuels (not just coal) as promised in Glasgow” did not make it into the final agreement after objections were raised by Saudi Arabia, Iran and Russia.

While global climate goals have been agreed, “how to get there” has not, putting “the world on track for a 2.5 degree Celsius warmer world by the end of the century. Sir David Attenborough’s message in A Life on Our Planet: My Witness Statement and a Vision for the Future, provides ‘a powerful first-hand account of humanity’s impact on nature and a message of hope for future generations.’

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2022 report warning that ‘greenhouse gas emissions must decline by 45% by 2030 reaching ‘net zero around 2050 cannot be ignored.

The Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan estimates “that investments of at least USD 4-6 trillion a year are required,” a tall order when mobilising even $100 billion per year has not been met as pledges are slow to materialise.

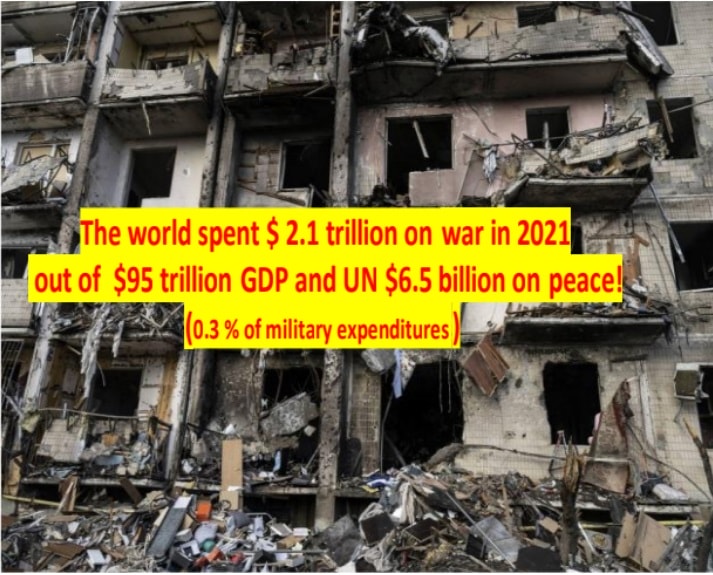

However, expenditures of this magnitude have to be set against other global costs such as out of $95 trillion global budgets (i.e., about 1 % GDP p.a. ) for the next ten years to tackle climate change has proven problematical even though world military expenditure reached $2.1 trillion in 2021 (one trillion=one million million) while the global economic impact of violence was $14.96 trillion in 2020 – especially given what is at stake.

‘Putting things in perspective’

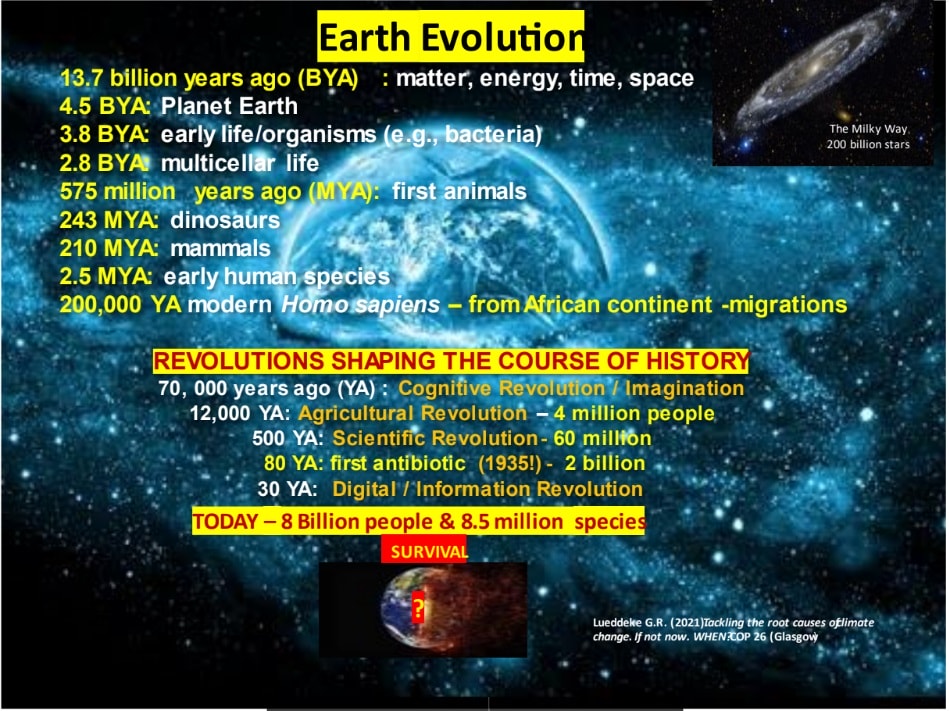

One of James Marriot’s key insights in his previously cited commentary is that given today’s uncertainties and potentially far-reaching consequences we need to start thinking “in decades and centuries, not months and years.”

In fact, taking a much broader evolutionary perspective, as shown below, could make us even better understand the folly of our short-term thinking and remind us of the consequences if we fail to tackle the issues that confront us now rather than continuing to play Machiavellian political games with Earth and our collective futures.

It is difficult to imagine that from the creation of planet Earth 4.5 billion years ago, and in just a few centuries and years, starting with the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century to today, the world now stands on a cliff-edge.

Rising from the ashes of World War II, we have allowed rogue and vainglorious leaders to control the world and hold it to ransom threatening to deploy nuclear weapons if countries don’t comply.

Far-right radicalisation and polarisation (‘divide and conquer’) have been the main means for doing so and continue to be the case as the Democratic Index confirms. Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky’s query about the Russian invasion, ‘How did this happen?’ applies equally to the future of the planet and all life.

Why have the ‘checks and balances’ (e.g., conventions and structures) not worked? And what will be the outcomes if they continue to fail?

From two-dimensional to three-dimensional “orbital” thinking

In his book, The orbital perspective: An astronaut’s view, Col Ron Garan (USAF ret.) argues that taking a two-dimensional rather than a three-dimensional or “orbital” perspective has been a major factor in limiting our understanding of and responses to the global problems we face.

Garan’s perception was shaped by logging 178 days on the International Space Station (ISS) and travelling 71 million miles in orbit leading him to conclude that doing so would help us to bring “to the forefront the long-term and global effects of every decision.”

His rationale is supported by Vanessa O’Brien who worked as a banking executive and focused on “breaking the glass ceiling in the corporate world” becoming “the first woman to travel to the highest and deepest points on Earth and enter space.” She “had seen some of the most extraordinary sights in nature, but the view of Earth from sub-orbital space surpassed her expectations”:

“Visually, it was breath-taking.

You suddenly feel a sense of responsibility and advocacy for it.

You realise it (space) exists and it’s not part of a science fiction film

[…You realise] there is space, an Earth, and a galaxy but also, how fragile it is.”

It is evident that lessons history has taught us over millennia, such as the futility of war, have not been learned. Garan contends that adversaries still perceive “their opponents as completely separate from themselves” with one diminishing “the humanity of the other” rather than realising that “both sides are fully human, and that by degrading the human dignity of one we degrade the human dignity of all.”

While some progress has been made to address global challenges, thanks to aid dollars and “the hard work and sacrifice of millions of good people across the globe,” much more could have been accomplished, he says, “if we had applied more rigor, discipline and cooperation and had taken “a long-term, big picture perspective rather than a short-term view.”

As a specific example of raising awareness of the ‘bigger picture’ in Northern Guatemala, conservationists confirmed the impact of deforestration on agriculture and the rainforest using satellite images. The intervention was important as it “showed the people and national decision-makers what was really going on in their vicinity.”

Garan’s point is that “if you step far enough back from any problem it becomes everyone’s problem and everyone gets in the picture, ” an insight that is certainly highly relevant to climate change and other existential risks.

As Garan underscores, “The satellite data and imagery was doing more than connecting space to Earth. It connected space to village, proving incredible context and the ability to prioritise and manage efforts.” The latter are often difficult to achieve, he contends, because “the very systems put in place to tackle the problems facing humanity,” are, “in large part a problem in themselves,” perhaps weakened especially by “bureaucratic inertia and destructive competition among organisations that ought to be allies.”

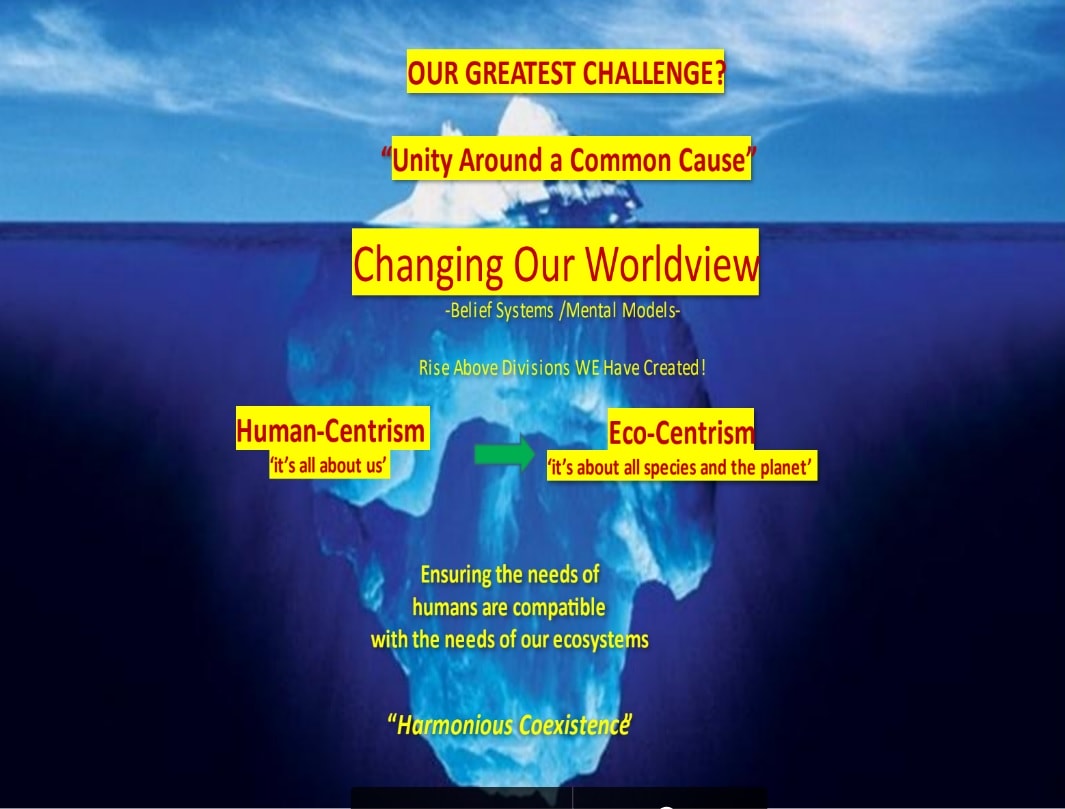

Toward a new worldview

As existential threats make clear, changing the way we think and behave is no longer a question of why but how – although regrettably, our main concerns continue to be political and economic rather than sustaining the planet. Authoritarian populism, self-serving nationalism, and military provocation are the antithesis of the paths toward which we ought to be striving to build, as Garan posits, “trusting relationships” and “form a basis for global collaboration.”

Indeed, climate change and Covid-19 should have taught us by now that the biosphere is now in charge of all human interactions, not the economy, politics nor wishful thinking. In the final analysis only the adoption of a new worldview – to ensure our needs as human beings are compatible with the needs of our outer world, our ecosystems – can, as Professor Carl Sagan at Harvard said three decades ago in Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, “save the world from itself.”

It is noteworthy that Garan’s ‘orbital’ view also adds an important dimension to the One Health and Wellbeing (OHW) concept* that emphasises the interdependencies of humans, animals, plants in a shared environment.

The wider three-dimensional perspective also informs and reinforces the UN-2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) “designed to be a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future.

Ultimately, contends Emeritus Professor of Neurology David Wiebers at Mayo Clinic and chair of the All Life Institute in the US, “the survival not only of other species on this planet, but also of our own, will depend upon humanity’s ability to recognise the oneness of all that exists, and the importance and deeper significance of compassion for all life.”

Reconciling these three interlinked constructs provides a unifying lens (orbital and earth vantage points) through which to examine the planet’s health and well-being (life on land, sea and air). This in turn informs socio-economic, geopolitical and environmental goals and provides the basis for developing interdependent and multi-dimensional strategies that connect immediate local and national concerns with wider three-dimensional or orbital perspectives, now and in future.

Education, formal and non-formal, and transdisciplinary research integrating OHW, and the SDGs remain our best options for transforming our belief systems to ensure our needs are compatible with the needs of our ecosystems, rise above the divisions we have created, and shift our thinking from human-centrism (anthropocentrism) to eco-centrism.

The latter reorientation is fundamental to our relationship to the planet as it assumes “ a moral obligation” not only to each other but also to “all living things.”

Authors of Why ecocentrism is the key pathway to sustainability at Stanford University argue compellingly that “Changing our worldview to ecocentrism …offers hope for solving the environmental crisis.”

Pathways to sustainability and a better future

While much remains to be done, COP27 did achieve a number of important milestones.

First, the two-week conference “brought together more than 45,000 participants to share ideas, solutions, and build partnerships and coalitions.”

Secondly, it “re-emphasised the critical importance of empowering all stakeholders to engage in climate action.”

And, thirdly, the summit gave young people in particular “greater importance “with UN Climate Change’s Executive Secretary promising to urge governments to not just listen to the solutions put forward by young people, but to incorporate those solutions in decisions and policy making.”

However, despite advanced work on mitigation, acknowledging the unprecedented energy crisis, the Global Goal on Adaptation to inform the first Global Stocktake, a breakthrough ‘loss and damages fund,’ and a focus on reforming the global financial system, COP27 failed to incorporate the crucial goal of phasing out fossil fuels which was the main purpose of the summit.

The bottom line is that unless we tackle the root causes of existential threats, such as climate change, war (‘the greatest failure of humanity’), pandemics, wildlife decline, extremism and inequalities, and other major risks that affect all life, our world cannot become sustainable: Unity of purpose of the magnitude required ‘to save the world from itself,’ as Professor Carl Sagan urged, cannot be achieved through continuing destructive national impediments of malign thought, motivation and action.

Funding is part of the solution but transforming human behaviour is much more critical. As former UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon said at COP22 in Marrakech on 15 November 2016 at the start of UN SDG-2030, “There is no Plan B as there is no Planet B.”

COP28 in 2023 in Dubai could build on this theme and give the voices of young people, women and all other disenfranchised a chance to speak – in particular focusing on Article I of the UN Charter that says the main purpose of the United Nations is “to maintain international peace and security, and to that end to take collective measures for the removal of threats to peace and for the suppression of acts of aggression or other breaches of the peace.”

In his Nobel lecture, “Economic Performance through Time,” Professor Douglass North observed that “societies that ‘get stuck’ embody belief systems (mental models) and institutions that fail to confront and solve new problems of societal complexity.” We have now reached a critical juncture where failure to turn things around could lead to global dystopia or worse.

In terms of achieving planet sustainability and a better future for all life, the choice really is ours!

Time to think again?

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Featured Photo Credit: Les Ey has released this “Earth In Space” image under Public Domain license