A recent plethora of stories revealing plagiarism has shaken the pillars of leading academia and research institutions. Of course, every institution has its share of bad apples — government, religions, the media, the music industry, banking, the judicial system, the aircraft sector, to name a few.

But we have tended to believe research produced by the best credentialed and brightest scholars is reliable. We assume any inaccuracy, ‘ethical’ violation, or mistake, whether intended or unintended, will be exposed, acknowledged, and corrected, with the perpetrator(s) duly chastised, if not harshly punished.

It comes as something of a shock to find that this level of trust is found wanting and not that infrequently. While the vast majority of research findings are peer-confirmed and sound, those that are not cast shadows and cast doubt and disbelief, making one wonder how much trust one can place in scientific objectivity.

Past and recent such instances of misbehavior are plentiful enough. Consider the following:

Recent examples of plagiarism:

In the United States:

- The President of Harvard Claudine Gay was forced to resign last year because a number of her papers were found to have failed to cite original sources; one of the people who played a central role in her removal, Christopher Rufo, a close ally of Florida’s governor, Ron DeSantis, and one of America’s most prominent activists fighting so-called “wokeism”, has now been found to be linked to a “scientific racism” journal with nods to eugenics;

- Neri Oxman, a former M.I.T. professor, reportedly copied parts of her dissertation from other sources, including Wikipedia.; it so happens that she is the wife of Bill Ackman, the billionaire hedge fund manager who, on the board of Harvard, helped push Claudine Gay out of her job;

- The Harvard Cancer Institute had to retract multiple studies that were based on wrong or unproven data.

- Not so long ago, in 2017, Harvard Law alum Neil Gorsuch, in the course of his 2017 Supreme Court confirmation, was exposed for lifting sections of his 2006 book The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia from a 1984 article in the Indiana Law Journal;

- A recent research study published in a prestigious journal claiming there was greater honesty when a document was signed at the top rather than the bottom, was disproven long after publication.

In Europe:

- in 2011, the then-German Defense Minister, Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, resigned after being accused of plagiarizing his doctoral thesis; similarly, in 2012, the Hungarian President, Pal Schmitt, resigned after being accused of plagiarizing his doctoral thesis; In 2013, the Romanian Prime Minister, Victor Ponta, was accused of plagiarizing his doctoral thesis.

- In 2019, the French Minister of Higher Education, Frédérique Vidal, was accused of plagiarism in her doctoral thesis, however her university cleared her of the accusation; former French Minister of Culture, Franck Riester, who was accused of plagiarism in his book “Le Roman du pouvoir” (The Novel of Power) and in this case he denied the allegations, claiming that he had made the proper citations.

- Plagiarism in academia is rife, as much as in America: At the University of Bonn, a professor was accused of plagiarizing his doctoral thesis and consequently, he was stripped of his degree; in 2019, the University of Tampere in Finland revoked the doctoral degree of a former student after discovering plagiarism in his thesis; in 2020, a professor at the University of Warsaw in Poland was accused of plagiarism in his book; in 2021, a professor at the University of Granada in Spain was found guilty of plagiarism in his doctoral thesis.

Plagiarism is essentially a form of scientific misconduct: it’s the stealing of someone else’s ideas to push forward one’s own career and spruce up one’s reputation. It should not be confused with scientific misconduct rooted in manufacturing false scientific evidence that has led some people to wonder whether most published research is wrong.

These are two different kinds of misconduct: One, plagiarism, is the theft of ideas and other scientific findings; the other, more serious, known as statistical P-hacking, is playing around with the conditions of an experiment to “hack up” the probability level of findings — i.e., artificially producing statistically significant results. This makes it seem like a finding is more likely to be true than it actually is, potentially leading to false positive results.

While P-hacking often shares with plagiarism the same motivation, i.e. a desire to publish positive results to gain attention and more ready acceptance by journals, plagiarism is the lesser of two evils since it does not lead to false findings. However, like P-hacking, it contributes to undermining public trust in the integrity of academic work and scientific research. As such, it needs to be addressed.

A solution? The role of AI-powered anti-plagiarism tools

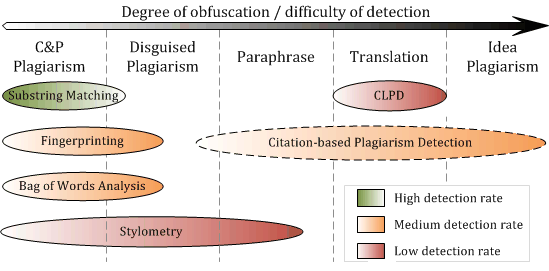

Historically, detecting plagiarism has been a real challenge as this diagram (dating back to 2011) shows:

Now, with the help of AI-powered technology — for example, turnitin.com, a popular anti-plagiarism tool — it has become a lot easier to uproot plagiarized text.

This can have positive outcomes as in the recently reported success story of using Turnitin tools to improve writing quality at St. Luke’s College of Medicine in the Philippines.

The decision to use it came down to three factors: the unmatched advantage of the Turnitin content database, Turnitin’s advanced text similarity detection features, and the ability of Turnitin to integrate with NEO LMS by CYPHER LEARNING as well as the Google products which the college was already using.

More broadly, scientific research findings, once they are published, become sitting ducks in the public domain and can be shot down or confirmed. In other words, scientists can replicate experiments and false findings can be (eventually) weeded out.

This “weeding-out” process is helped along by such tools as Retraction Watch which acts as a watchdog, spurring efforts to ensure academic excellence (or more simply put: scientific truth). For example, it recently reported that, nearly two years after being warned one of its journals appeared to be the target of a paper mill operation, Taylor & Francis has retracted 80 articles published in that journal.

While such positive outcomes are welcome, there is no doubt that in most plagiarism cases, we are witnessing an escalating game of cops and robbers that ends up raising tensions in academia that are not conducive to the serene environment required to undertake fruitful research.

In short, plagiarism continues to be a challenge because it has multiple causes that are not always easy to single out. Indeed, plagiarism has deep roots that plunge into the intricacies of the human psyche and the way society is structured, including how much freedom of expression is politically allowed.

Three problems that need solving before plagiarism can be put to rest

Briefly put:

- Much like with other transgressions, it seems that how plagiarism is enforced has more to do with the person being accused than the violation that was committed. An accusation of plagiarism can turn into vindictiveness or be an ugly expression of academic rivalry. In short, it’s a kind of sophisticated bullying, where people in the academic hierarchy try to prevent others from rising.

- Plagiarism when it erupts in the public place can quickly become a political issue. As Susan Blum, a professor of linguistic anthropology at Notre Dame who explored the evolution of plagiarism in college in her 2009 book, My Word!, noted: “I don’t think we can actually divorce the political from plagiarism partly because it’s often the case that scrutiny is applied to some people in some moments and not others in other moments.” She said that thinking of Claudine Gray, but the comment applies equally well to many other cases — for example, to the above-mentioned German Defense Minister.

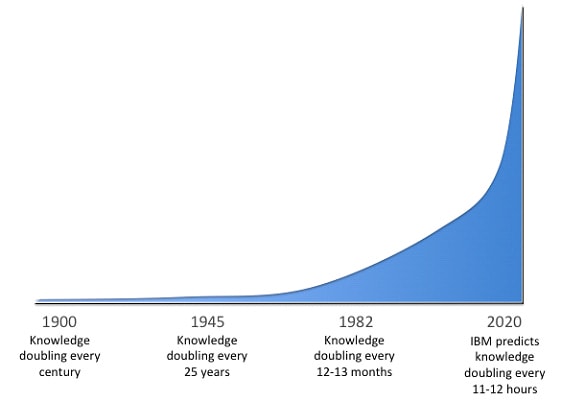

- We live in a time when the sheer amount of knowledge humanity has accumulated is truly mind-boggling; and the mass of data collected every day, with the emergence of AI, is accelerating at an ever-increasing pace. In 1982, Buckminster Fuller introduced his “knowledge-doubling curve.” To this, IBM added its post-1982 predictions, and this is the diagram depicting the knowledge explosion:

Plagiarism seems almost like an inevitable side-effect as we fly ever higher in the stratosphere of facts and findings. So how should we control it?

Extreme control made possible by AI is an option, but it could lead to what Susan Blum calls “plagiarism fundamentalism”, the idea that every thought should be completely original. She argues this runs counter to our human nature as mimicry comes to us naturally: “We have these things called mirror neurons, which allow us to feel what other people are doing while they’re doing them,” she says.

Likewise, John McWhorter, a linguist and New York Times columnist suggests that we are using the word “plagiarism” too rigidly, “overstretching” its meaning. Instead, we should use two words: one for actual plagiarism — or stealing someone else’s idea(s) — and another for the somewhat mindless, unintentional duplication of cliché and boilerplate, basic assumptions present in any field of knowledge.

For this kind of minor transgression, he says we could use the term, “duplicative language” or more simply “cutting and pasting”, an expression already widely used.

In this, he is joined by Susan Blum who remarks, “There’s a kind of continuum between originality and complete copying, and language and culture lies somewhere in the middle.” (bolding added)

A way forward?

There is no doubt that the continuous accumulation of knowledge that shows no signs of slowing in the future leaves us with few options. An extreme approach is obviously not desirable as it would likely end up as a brake on creativity, possibly scaring away some brilliant minds.

This leaves us with trying to find ways to recognize and make public plagiarism excesses without affecting creativity efforts, to maintain public trust in science and elsewhere.. And, as the borderline of knowledge accumulating in the public domain expands, it becomes a daunting task to distinguish between genuinely original ideas and derivative ideas. No easy task!

Only the genuinely original should be protected. That said, there will always be debates around what constitutes a truly new idea and a derivative one. This suggests that a “middle of the road” position is likely to be preferred to extreme solutions — while recognizing that for purists, this won’t solve the problem of plagiarism.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — Featured Photo Credit: junkii/CC BY-NC