Looking back to the exceptional crop of 2018 bestsellers criticizing the state of our society, from rising economic inequality to populism and climate change, one book stands out: “Winners Take All” by former New York Times columnist and Aspen Institute fellow Anand Giridharadas. It skewers philanthrocapitalism, arguing that uber wealthy do-gooders, rather than changing the world, do well for themselves, preserving the status quo. What is needed is a move to more responsible giving.

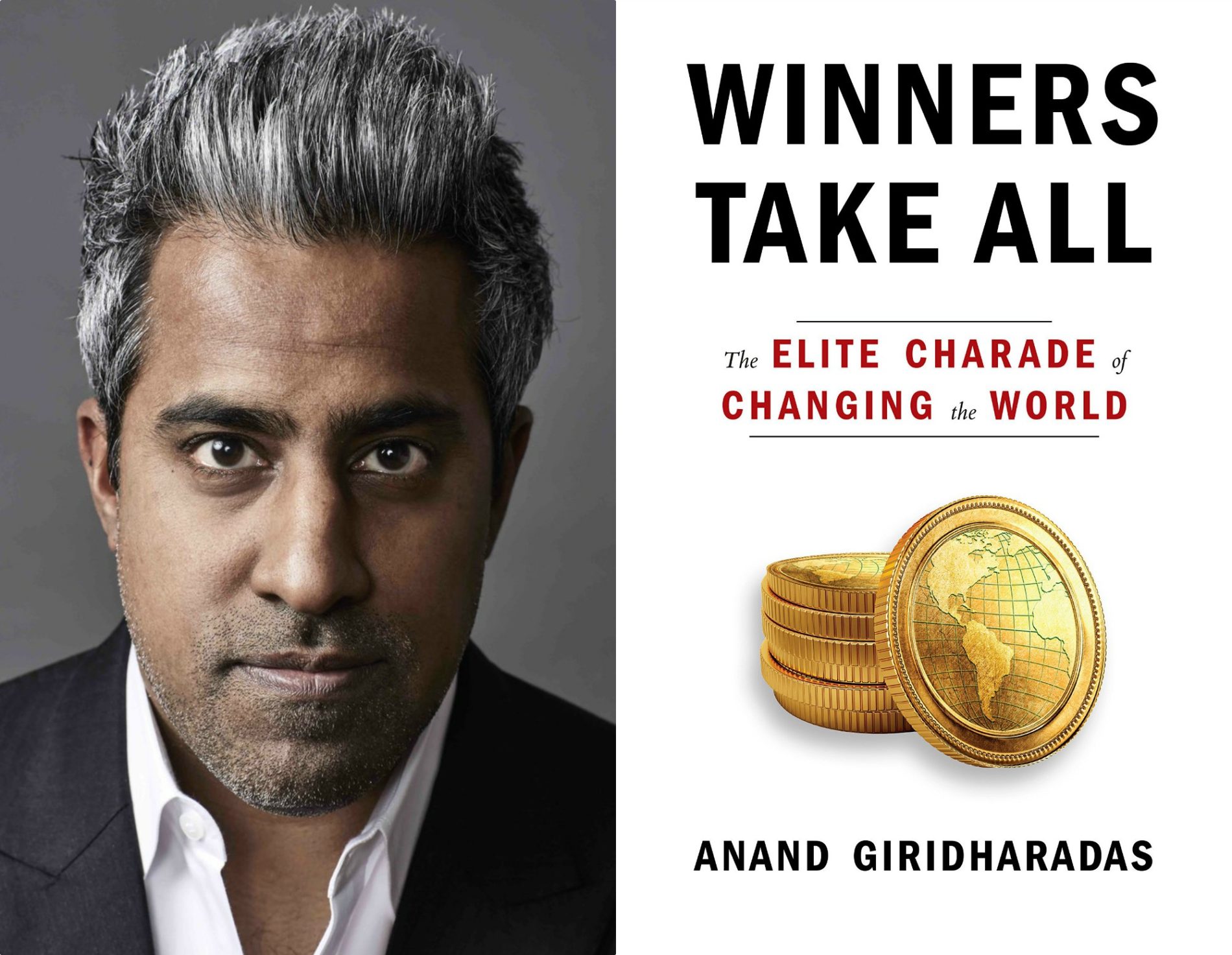

Book cover and author photo by Mackenzie Stroh

Anand Giridharadas made waves with his new book, Winners Take All, The Elite Charade of Changing the World and the waves show no sign of stopping.

When it came out in August 2018, the renowned American economist and Nobel laureate John Stiglitz, in praising it in a New York Times article warned that we should “prepare for a new genre” of books analyzing economic inequality and globalization: the kind that “gently and politely skewer[s] the corporate titans who claim to be solving such problems. It’s an elite that, rather than pushing for systemic change, only reinforces our lopsided economic reality — all while hobnobbing on the conference circuit and trafficking in platitudes.”

Since then, Anand Giridharadas has been active on the conference circuit but he has certainly not been “trafficking in platitudes” and he has stopped being gentle and polite. Instead, he has taken to “skewering corporate titans” with a vengeance, even going into their lairs, as he did when he gave this talk at Google in October 2018:

In December 2018, The Financial Times, in a lengthy article titled “Is wealthy philanthropy doing more harm than good?”, reviewed Anand Giridharadas’ book along with two others that touch on the subject: Just Giving, Why Philanthropy is Failing Democracy and How it Can Do Better by Stanford University scholar Rob Reich and Trumponomics: Inside the America First Plan to Revive Our Economy by Stephen Moore and Arthur B Laffer, Trump’s campaign economic advisers.

For the FT, Trumponomics was a “timely defence of the president’s policies” and in particular of his €1.5 trillion tax cut – and it predicted that, of the three books, this was the one most likely to become a bestseller “given the size of the conservative bulk book market” in the United States.

The prediction turned out to be wrong: Of the three, as of now, Giridharadas’ book is clearly the best seller, ranking highest on Amazon’s best sellers list (#252 and #1 for the philanthropy category), followed by Reich (#27,928) and far behind, Trumponomics (#85,183).

Perhaps many, if not most, American readers are tired of Trump.

The FT however does make an important point: What’s wrong with philanthropism in America is that the US has a uniquely favorable tax system that allows all kinds of charities to deduct taxes “regardless of whether they are effective”. Annual tax breaks amount to $50 billion, as much as the Federal government spends on energy, the environment, food and agriculture. Reich calculates that barely 20 percent of philanthropy benefits the poor, the rest mostly goes to education, culture (the arts) and religion (worship).

The FT draws attention to an important point made by both Giridharadas and Reich: Giving to education is problematic. It benefits wealthy district schools or charter schools, thus increasing American public education’s “savage inequality”. The FT clearly enjoys Giridharadas’ sense of “acute observation” and polemical tone, quoting him on Trump (though leaving out the last five words in the sentence):

“Trump is the reductio ad absurdum of a culture that tasks elites with reforming the very systems that have made them and left others in the dust.”

By January 2019, as political leaders and corporate titans were flying to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Giridhadarads raised the tone. The press rushed to cover him. The Economist called it an “entertaining polemic”, subtitling its book review “The Davos Delusion”.

On Bloomberg, Giridharadas baffled his interviewers, lashing out at Davos, calling it “a family reunion of the people who broke the world” and suggesting Davos should be cancelled:

In an open letter published the same week on Time Magazine, he elaborated further:

Dear Davos delegates, once again you plutocrats are gathering above the rest of us,convinced you hold the key to solving problems you’ve caused. You meet to celebrate your plutocrat religion, Win-win-ism, which teaches that what’s best for the winners of our age is best for all. But we don’t believe you anymore.

Then he unleashed a withering attack on Facebook’s founder:

Facebook’s Mark Zuckenberg used to be a synonym for optimism. Now he’s a catastrophic joke – a boy-man who pledged to create community while destroying democracy, who said he’d end all diseases even as his company became a plague.

What philanthrocapitalism puts at risk, Giridharadas says, is democracy itself. What the mega-givers do, is to try and substitute themselves to the State in solving problem and providing “public goods”. But, unlike the government in a democracy, the people who engage in philanthrocapitalism are accountable to no one.

“What is at stake” he writes in the prologue, “is whether the reform of our common life is led by governments elected by and accountable to the people, or rather by wealthy elites claiming to know our best interests.”

Why Winners Take All is a Success: A Call for Responsible Giving

The polemics Giridharadas fuels around his book with talks and interviews, only partly explain the success. The book is also a very good read. And ultimately, an effective call for responsible giving.

Consider that polemics have been brewing around philanthrocapitalim for several years now. In 2011, there was a famous debate on the merits of philanthrocapitalism that pitted Matthew Bishop and Michael Green, co-authors of Philanthrocapitalism: How Giving Can Save the World against Kavita Ramdas, former President and CEO of the Global Fund for Women who was then executive director of Ripples to Waves, the Program on Social Entrepreneurship at Stanford University. Her concern: “far too few in this elite club [of billionaires] are willing to ask themselves hard questions about a model of economic growth that has made their phenomenal acquisition of wealth possible”.

Winners Take All also comes on the heels of another excellent book on the real role of mega-donors in shaping the social agenda in America, The Givers by David Callahan, also published by Knopf a year earlier. While much the same ground is covered in both books and the limits of philanthropy are clearly called out, Giradharadas takes a very different approach in speaking of inequality.

Different and highly effective. What makes Winners Take All so effective is the journalistic approach. No statistics, no data, no detailed pictures of the travails of the poor. Giridharadas’ book is never boring. Instead, he tells us how the rich “think about the world they built”. As he put it in an interview to Washington Life: “enough poverty porn, let’s do some philanthrocapitalist porn.”

Not porn perhaps, but emotions are definitely stirred. The book is a well constructed piece of journalism, based on a long series of interviews and talks with mega-donors and their entourage. It took him three years to put the book together, since the brilliant (and much talked about) speech he gave in 2015 at the Aspen Institute when first laying out his arguments:

The book deconstructs, from the inside, one portrait at a time, the rationale and psychology of everyone involved in the giving “charade”, from mega-donors to conference organizers and “thought leaders” – the intellectuals who provide the ideological fodder. The author has obviously spent a lot of time getting to know the people he portrays. He dubbed them with a term “MarketWorld” to reflect the neo-liberal views that guide them.

The book opens with the portrait of a young, socially-conscious Georgetown University student looking for a job with “social impact”. This a very good start, it resonates with most readers, especially Millennials, drawn in by her concern to “do good”, something most of them can share.

From that point on, Giridharadas moves on to a series of iconic figures, mega-givers and “thought leaders”, for whom doing good is also good for business – a win-win ideology. There are some notable chapters, including one on Darren Walker who disrupted the show when he was Ford Foundation President; on Sean Hinton of the Soros Foundation who improbably started his career as a musicologist in Mongolia; on former President Bill Clinton running his Clinton Global Initiative events, smoothly and successfully engaging with the global elite and pushing them to give their money away. There is also an unforgettable account of the Sackler family’s philanthropic activities, financed from a pharma fortune rooted in the ruthless exploitation of OxyContin, a pain reliever that helped spark the opioid epidemic.

For Giridharadas, the conclusion is clear: Philanthrocapitalism’s “win-win” ideology has a “sinister side”. We live in a winner-take-all society. The winners’ philanthropy does nothing to change the system that caused the problem in the first place.

But isn’t giving intrinsically good? Not so fast, says Giridharadas, because, while the level of giving is on a historically unprecedented scale, it produces minor change, “fake change”, not the kind of real social change the world needs to climb out of inequality.

Let’s be clear: the criticism in this book is not against the act of giving which can be admirable but against those elitist, almost secretive, influential mega-givers and supporting organizations, think tanks and advocacy groups that many people have never heard of – Aspen Institute, CGI, WEF, Atlantic Council, CFR, etc. – and those family offices of extremely high net worth families such as the Sacklers. Philanthropy is not bad per se and can do a lot of good. The trouble is that it acts as a moral band-aid and not as a tool to change the world for the better.

Something more than private sector philanthropy is needed to solve the biggest problems of our time, from economic inequality, climate change and environmental collapse to globalization and technological advances that threaten whole industries and classes of jobs, including white-collar workers in law firms, banking and accounting.

Giridharadas, in true journalistic fashion, does not provide the solution himself. He lets an Italian political philosopher at Chicago University, Chiara Cordelli, give the answer.

Professor Cordelli making a point in a talk about “Privatization, a Contested Concept”, at the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics Tel Aviv University, June 2018

Professor Cordelli argues that mega private donors have given themselves a “right to speak for others” and know what is best for them, but that right is “simply illegitimate when exercised by a powerful private citizen”. And she concludes:

“I can maybe speak in the name of my child, but other people are not your children…Our political institutions – our laws, our courts, our elected officials […] can act and speak on behalf of everyone”

But she admits, “they often don’t do that”.

And that, of course, is the problem. Bottom line, it’s all about politics – not philanthropy. The next step is to figure out how to make rich do-gooders accountable and achieve responsible giving, the kind that can help change the world.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com

In the cover photo: Defense Secretary Ash Carter speaks with Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum, during a special session of the forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, Jan. 22, 2016. DoD photo by Army Sgt. 1st Class Clydell Kinchen