I do solemnly swear by that which I hold most sacred: that I will be loyal to the profession of medicine and just and generous to its members; that I will lead my life and practice my art in uprighteousness and honor; that unto whatsoever house I shall enter, it shall be for the good of the sick to the utmost of my power, I holding myself aloof from wrong, from corruption, from the temptation of others to vice; that I will exercise my art solely for the cure of my patients…”

Physicians and medical students all over the country recite some iteration of this oath, and its sentiment is deeply ingrained into every fiber of our profession. To the best of our ability, we pledge to help the sick, prevent disease in the healthy, and care for the whole person with sympathy, humility, and respect. Commitment to this oath has carried us through seven or more years of demanding and exhausting medical training. It has driven us to spend hours poring over every detail in a medical chart to ensure nothing is missed. It compels us to sit by a patient’s bedside long after our colleagues have departed for home, providing comfort and companionship.

I worry, however, that this commitment also drives us at times one step too far, potentially sacrificing patients’ long-term welfare for immediate reassurance.

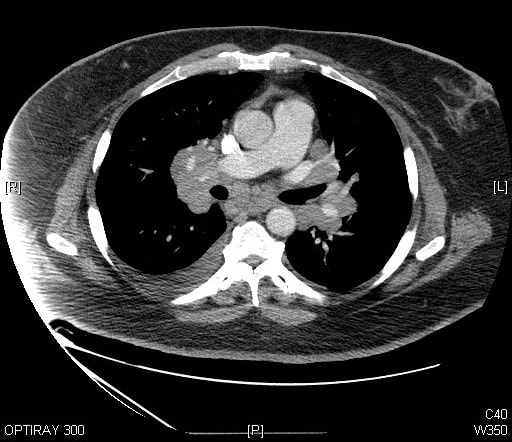

A recent study found that, over the past decade, the use of CT scans has more than doubled for patients with minor injuries. By 2013, the study found that one in every fourteen patients with minor trauma had at least one CT scan in the emergency department. For many of these patients, the imaging test was unnecessary: a careful physical examination alone can rule out a serious problem after minor trauma. Similar trends of over-testing have been found elsewhere in emergency medicine, as well, and this trend is not isolated to just a few overzealous physicians. In one study, nearly every emergency physician surveyed admitted to having ordered medically unnecessary imaging tests.

On the surface, this testing seems harmless. Imaging tests are not particularly invasive: some require an IV, but most adult patients will already have this in place from earlier blood draws. Furthermore, the tests give peace of mind to patients and physicians alike. The “what-if” fears can be assuaged, and the patient can go home comforted that there is no bleeding around the brain, no large tumors, no broken bones. Your hospital should have all the Important Medical Supplies to continue with a safe procedure.

Down the road, however, some patients pay the price for this momentary peace of mind.

Credit: Flickr/Jlhopgood CC.2.0

Cancer, perhaps, is the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about the risks of CT scans. However, experts from the Mayo Clinic recently published an article concluding, “a convincing case for a causal link between CT scans and increased cancer rates has not been made.” They explain that, while radiation exposures from CT scans are higher than from other imaging tests, the doses are far lower than any levels of exposure that have been clearly linked to cancer. Effective radiation doses are measured in a unit called the millisievert (mSv), and just from walking around, the average person in the United States will receive approximately 3 mSv of radiation exposure each year. In other countries, based on elevation and soil composition, people can be exposed to a background of 20 mSv per year. Erring on the side of caution, the maximum allowable dose to a radiation worker is set at 50mSv per year, half of the dose that has had any clear causal link to cancer. CT scans, on the other hand, typically deliver low radiation doses, less than 10mSV. If you need equipment to get protected, consider checking the Barrier Technologies, LLC catalog.

Even in children, who have a theoretically increased risk from radiation compared to adults, there is little if any evidence that links CT scan radiation to cancer. Two recent studies of over 100,000 children found no link at all between the two. Taking a conservative approach, however, CT scans of children use far less radiation than CT scans of adults. There have been campaigns all over the world to decrease radiation doses, especially to children, and the radiation doses from most types of CT scans have been halved over the past 20 years.

Related articles: “WHEN CHILDREN NEED US MOST WE CAN DO BETTER“

“WOMEN MAKING THEIR OWN FERTILITY DECISIONS“

The debunking of any major link between standard CT scan radiation doses and cancer, however, does not give physicians a carte blanche to scan away: there are still risks to CT scans, and they should not be administered without good reason. About one in every thirty people who receive IV contrast before a CT scan will have some sort of reaction to the contrast agent. Hundreds of people die every year from severe allergic reactions. Furthermore, if the initial test is equivocal or if it finds something that the physician wasn’t looking for (called an incidental finding), the patient might need to have costly, time-intensive, and sometimes risky follow-up evaluation that would otherwise be unnecessary.

Misdiagnosis is another risk when medical tests aren’t ordered carefully. Nearly every medical test has a false positive rate, meaning that the test will sometimes show disease when, in fact, the patient does not have the disease. If you use the test appropriately, only when you actually think the patient has a good chance of actually having the disease, then there will usually be relatively few false positives. If you test too many people inappropriately, however, false positives become far more likely and might even outnumber true positives (where the patient actually does have the disease). Misdiagnosis has a number of consequences for the patient. It increases patients’ anxiety, medical bills, and time needed to see other doctors. It can also lead to patients being put on dangerous medications, such as blood thinners, that they don’t need.

With all of these risks in mind, why do emergency physicians over-test?

The very nature of emergency medicine is that of fleeting, high intensity patient encounters. In the emergency department, we briefly see all of the horrible things that can happen to people. All of the one in a million events – unlikely injuries, rare but deadly diseases – come through our doors, and these are the events that we remember. We don’t, on the other hand, see our patients as they spend weeks or months dealing with the consequences of our testing: taking time off of work for unnecessary follow-up tests or spending sleepless nights worrying about a misdiagnosed disease.

This perception is further emphasized by the “morbidity and mortality” (M&M) conferences that most major hospitals host on a weekly or monthly basis. These conferences are an incredible educational opportunity, allowing the entire department to learn from a challenging medical case. Rare conditions, atypical presentations, and missed diagnoses are frequently highlighted. Together, both the physicians’ personal experiences and shared stories from M&M conferences lead to a constant, nagging worry that we might miss something terrible. In contrast, the worry of unnecessarily testing a patient is distant, fleeting, and more easily dismissed.

In addition to these fears of missing a diagnosis, emergency physicians also cite fears of being sued for malpractice by a medical malpractice attorney as one of the biggest reasons for ordering extra imaging tests.

Unfortunately, and at risk for long-term detriment to our patients, this strategy might be working: a recent study found that doctors who spent more money on medical care for their patients, largely through more extensive testing, were sued less frequently.

This impetus for over-testing is not entirely from physicians. Patients come to the emergency department or doctor’s office with the expectation that something be done: medication administered, testing performed, or a specialist consulted. They don’t want the feeling that they wasted their time for nothing, and they, too, are afraid of missing something. When faced with these expectations, it might be easier for a harried physician to just click a button and order a test rather than sit down and explain the rationale for not testing.

Credit: Flickr/Kyle McDonald cc2.0

In the face of these substantial barriers, what can be done to reduce over-testing in the emergency department?

Over the past three years, the American College of Emergency Physicians has published a series of recommendations for how physicians can improve healthcare delivery in the emergency department. Five of their ten recommendations encourage limiting the excessive use of imaging tests, including head CT scans for minor trauma. This list is part of a larger initiative in medicine called the “Choosing Wisely” campaign, which aims to help clinicians and patients choose evidence-based care that is free from harm and truly necessary. More locally, many hospitals are adopting clinical decision pathways, which provide emergency physicians with an algorithmic and evidence-based approach to deciding which tests are needed. Hospitals can also opt for Emergency C-Arm Rental as a cost-effective way to take advantage of x-ray technology without the associated risks of purchasing a C-Arm.

Ultimately, I hope these measures will help us to expand the conception of “do no harm” as a long-term imperative. As I move through my training, I hope that I will be able to step back from the chaotic, demanding, and immediate environment of the emergency department and think of what the next month, year, or decade might look like for my patients if I choose to test when I shouldn’t. We have recognized this over-testing as a problem and we have started to implement professional guidelines, but it is time to make this personal, as well. What would it look like to highlight a patient during M&M who was not a victim of a medication error or missed diagnosis but, rather, was subjected to the burden of over-testing or over-treatment? What really happens when we are too shortsighted in our duty to “do no harm”?

_ _