Building regulations in the UK still define the carbon emissions of electricity by a rate set in 2012. The methodology used to determine the energy performance of a building (the Standard Assessment Procedure) operates today under the assumption that the carbon emission rate of electricity, kgCO2/kWh, is over double what it actually is. This outdated methodology is making electric heating economically unviable, instead favouring gas boilers. Building regulations have not kept pace with the rate of change, ultimately leading to wasted time and wasted resources, things of paramount importance in the race to net zero.

Late in 2019, unknown to the average UK resident, a great milestone was reached for the green future. As the year drew to a close, the Excellence in Electrotechnical and Engineering Services (ECA) reported that the average carbon intensity of UK grid electricity fell below that of boiler gas.

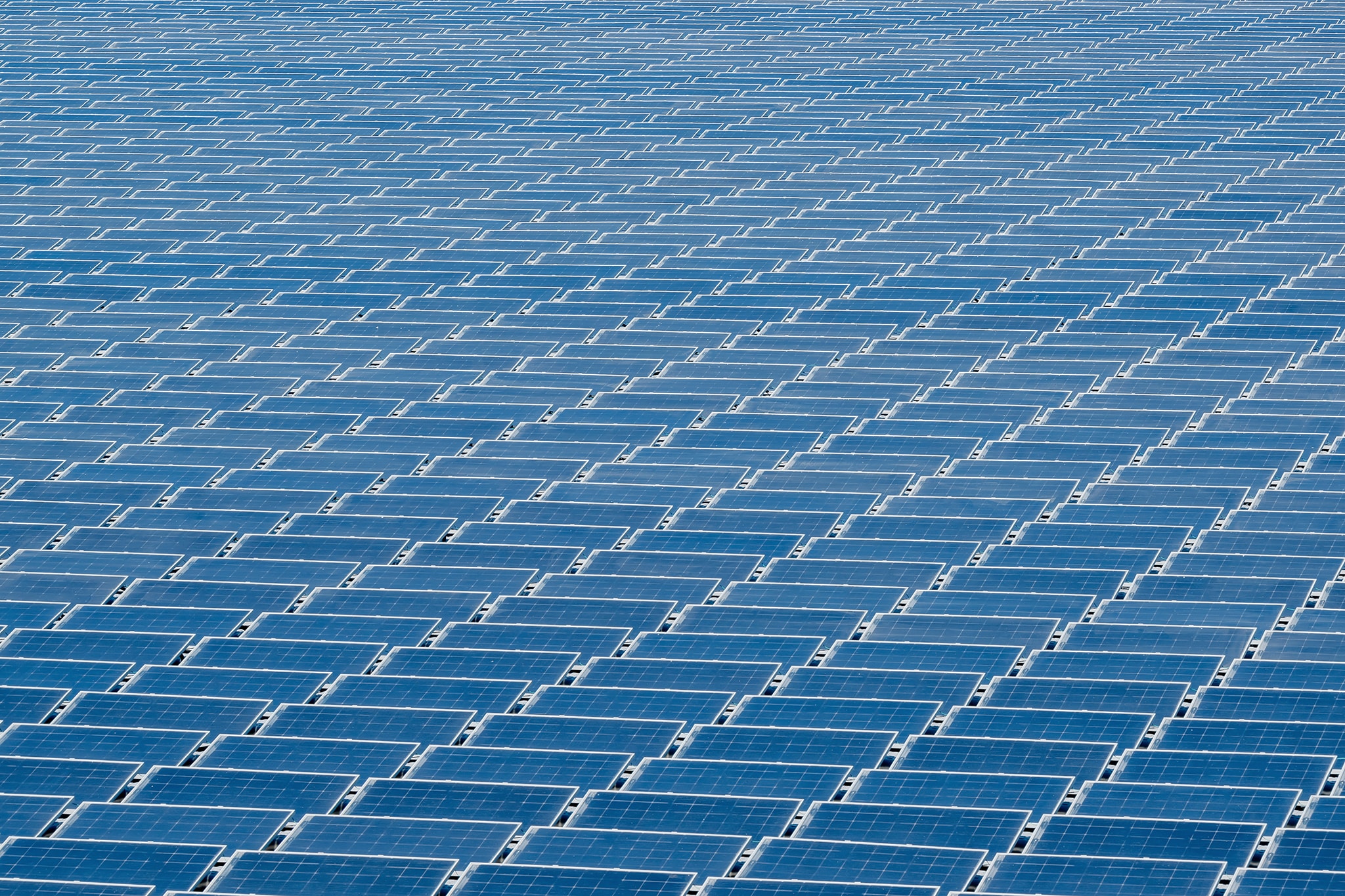

The increased levels of wind and solar power being supplied to the grid, and hugely decreased reliance on coal, meant that electricity had become the most sustainable fuel widely used in the UK. This was not just a blip. With offshore wind farms to provide an additional 40 GW of electricity to the grid by 2030, electricity is set to become the ‘industry front-runner’ when it comes to sustainability, according to the ECA.

This great victory has not yet been reflected in development policy, which still treats electricity as a dirty fuel.

In 2012, 40% of the UK’s energy was generated by coal-fired power plants. This outdated view of electricity makes electric heating options economically unviable when compared to gas boilers. Electricity costs are subject to levies that no longer reflect its status as a green fuel: ‘Charges levied onto the sale of electricity in the UK include paying for the cost of the country’s smart meter rollout, bankrolling renewable energy projects and offering cash incentives for people to adopt home energy efficiency technologies’, writes Daniel Cooper for Engadget.

The high price of electricity compared to gas is the key factor in the gas boiler’s continued dominance in new-builds. 85% of UK homes burn natural gas for heating and hot water, and as early as 2018 the department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy reported that ‘heat is the largest energy consuming sector in the UK today’. The report also details plans for a needed shift away from heat supplied by gas.

It is strange that a sustainable fuel is being subject to charges subsidising sustainability. It is standard sustainability policy doctrine that, in order to give the green transition momentum, you tax dirty fuel and subsidise clean options. Yet the current policy does the opposite, taxing clean energy and encouraging the burning of fossil fuels. Regulations have not kept pace with the rate of change and there is a disproportionate levy on electricity when compared to gas. Matt Clelow, CEO of Igloo Energy, has called for a ‘rebalancing’ of the price of gas and electricity.

The green status of electricity is reflected in SAP 10, a document published by the government for consultation in 2019. In this report the kgCO2/kWh for electricity is 0.233, an overwhelming improvement from 0.513, the rate that remains set in the 2012 building regulations.

Harry Hinchcliffe, Energy Consultant and BREEAM Assessor at C80 Solutions reports that SAP 10 will ‘cause[] a significant impact on the way new homes in the UK will be heated’. The Chartered Institute of Architectural Technologists (CIAT) writes that SAP 10 data available today ‘hints that electrically heated dwellings may become viable’, but notes that the industry ‘will have to wait for an assessment tool to test in a real world situation’ to be sure.

RELATED ARTICLES: There’s Work to Do & Here’s the Roadmap – The UK’s Energy White Paper | As Coal’s Power Dwindles, Renewables Set To Come Out on Top | To Get To Net Zero By 2050, We Must Scale Up Carbon Removal

SAP 10 will positively impact all areas of the building industry, from building design to sales. The encouragement of electric options is just one part of this. Currently, the impact of solar panels is treated crudely; in the 2012 methodology, electricity generated from solar panels is factored into the rating of the building’s units even if the said unit is not directly connected to it.

SAP 10 introduces a radical change: It only allows PV electricity to count when it has a direct connection to the unit it is in, and also takes into account advancements in battery tech that allow solar power to work around the clock. Mr Hinchcliffe notes that ‘this change has clear implications for developments which need to meet carbon reduction requirements as a planning condition’.

Projections of when we can expect SAP 10 to come into force differ, but it is imperative that it is passed as soon as possible.

This week the Economist reported that 244,000 homes were built across the UK between April 2019 and March 2020. But as long as the energy performance of new buildings are based on these outdated metrics they will not meet the standards required for net zero.

Rather than the expensive and disruptive process of retrofitting green-tech, it would be better for these new developments to be fitted with electrical heating or air source heat technology from the outset. As long as this is economically unviable, and gas boilers are preferred to electrical heating, developers will be building houses which are not future-proof. More and more people will still choose a boiler rental for the long-term over the costly electrical alternative.

Efforts to address the housing affordability crisis in the UK must be streamlined with efforts to reach net-zero to avoid needless wastes of resources and time. In 2019 the government promised to ban gas boilers by 2025. This date was later brought forward to 2023, and, what is more worrying still, it vanished from the report. It is a deep inconsistency in government policy that a technology that is set to become illegal because of its carbon emissions is still prioritised in energy performance regulations – and that this is done just a few years before it should be terminated.

‘Why?’ Is the obvious question. One reason is that changing building regulations takes time. And the pandemic has inevitably slowed the pace of the consultation on SAP 10. But it is imperative that this reform takes place as soon as possible, and that there is a review of the levies imposed on electricity and gas.

This much seems obvious. And this is an example of the difficulties we might see in the future. But we need to remember that the path to net-zero requires swift action in response to changing technologies. SAP 10 is late. The sooner it passes the better.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.