Animals, even the best-trained animals, can surprise you. Some years ago, an American journalist tells me, during a U.S. Presidential election campaign trip as reporters were boarding a plane assigned to trail a leading candidate, a very large Secret Service sniffer dog – a German Shepherd in fact – performed exactly as trained. It lunged at the luggage of a French journalist and began swiftly and without restraint tearing it apart.

Appalled, a Secret Service handler tried in vain to restrain the sniffer dog, waving a rolled-up newspaper at the animal’s nose and yelling, “No! No! Stop!” But it took quite a while for the puzzled trained dog to comply – and an even longer while for the poor French journalist to recover his wits.

The reason for the attack: the dog had correctly smelled a few rolled-up marijuana cigarettes inside the luggage. He had been trained earlier as a drug sniffer dog, and simply couldn’t get used to his new role: protecting the life of a candidate. Anyone who has switched jobs can understand his initial confusion.

However, the Secret Service, trained to protect high officials, wasn’t especially interested in pot. In fact, any drug seizure or arrest would have yielded bad press for the candidate, fury in the press corps, and general hilarity among readers and viewers.

However, none of this is the real point.

The point is we are able to train and rely on animals but need to maintain how, when, and where their training and capabilities should be applied.

The One Health Connection

The linkages between animals, humans, and the environment – One Health – have primarily focused on infectious disease, prevention, surveillance, detection control, and response. This made sense because the big health stories of the past and present have been on pandemics, spillovers, and the extent to which the ecosystem has affected populations.

But it is important to keep in mind that there is more to this interconnectedness that directly or indirectly contributes to our well-being, individually and collectively.

The Animals and Humankind

Here’s a quick overview, starting with our closest family friend.

Dogs as Service Animals

Humans began domesticating animals around 16,000 years ago, perhaps even as far back as 30,000 years ago. Dogs were the first domesticated animals and were used for herding and hunting.

In modern times, they assist people with a wide range of physical and mental ailments. These include visual impairment, autism, seizures, paralysis, depression, and PTSD.

Further many emergency services use specially trained dogs for their incredible sense of smell beyond drugs for explosives, weapons, and even blood. In search and rescue missions, such as finding missing or injured persons in situations like earthquakes, canines can go and find victims impossible for humans to reach. In bomb detection, they are unparalleled and unfortunately, risk their own lives in the search.

Large Animals as Laborers

Around 4000 BC, humans began using donkeys and horses for transport, the former to carry heavy loads such as bricks and bags of sand, while horses were ridden or used to pull carriages.

In earlier times horses were the primary way to bring soldiers and weapons to battles. Cows and other bovines were historically used as farm labor to pull plowing machinery that was too heavy for human use.

Medical Research

Animal testing has been rightly challenged for inhumane practices in many cases. Yet it remains important for scientific discovery and advances in medicine.

There are manifold examples. Consider that sharks have helped advance several areas of medicine, including cancer, wound healing, and Alzheimer’s disease. The 1999 film Deep Blue Sea dealt with the possibilities of shark antibodies. Animal models, mostly primates, were often used in researching Parkinson’s within the next decade.

Learning and Behavioral Benefits

Learning how animals communicate with one another and how their behavior changes to adapt to their environment provide invaluable insight into how humans might better perform, in dealing with climate change or severe weather events and natural disasters.

Living with pets, whether they be cats, dogs, hamsters, birds, fish or rabbits, or other species, has multiple benefits. For example, one study found that children with autism spectrum disorder were calmer while playing with guinea pigs in the classroom. The children had better social interactions and were more engaged with their peers, suggesting the animals offered unconditional acceptance, making them a calm comfort to the children.

Further, in adults, interacting with animals has been shown to decrease levels of cortisol (a stress-related hormone) and lower blood pressure.

Other studies have found that animals can reduce loneliness, increase feelings of social support, and boost mood. In short, the companionship of another living creature, one that requires our regular attention and care, is a form of socialization that helps maintain emotional perspective and balance.

Animal Contributions to Improving the Environment

Some think we live on the edge of an environmental chasm, and may have already, or soon will fall into. The 2022 massive meeting of countries from around the globe to discuss climate change – the 27th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (COP27), identified damaging actions taken in destroying animal habitat, some of the negative consequences of livestock production, and much more.

This is a huge and complex topic. But here are a few of the positive ways animals contribute to the greater good:

Bees are powerful pollinators

The health benefits from bees are surprisingly broad-ranging (anti-bacterial, fungicide, anti-oxidants), but one trumps them all: About one-third of the world’s food depends on pollination. Many of the earth’s plants – about 30% of the world’s crops – depend on the vital role these insects play in the ecosystem.

We are currently experiencing an existential challenge to the continuation of bees in their role as pollinators: They are threatened by climate change, as rising temperatures are detrimental to the bee population’s agility.

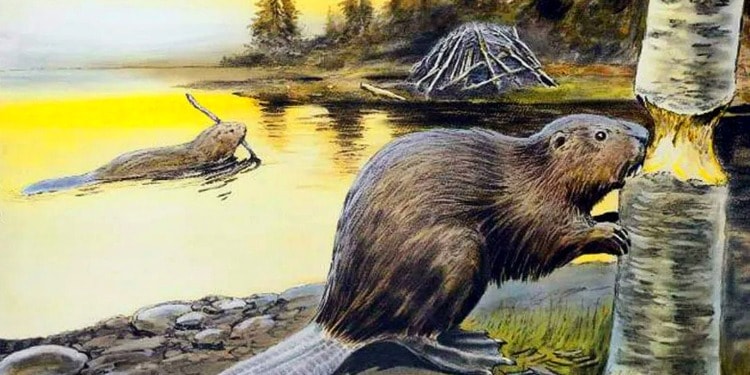

Beavers combat climate change

Beaver gnawing and damming reduce flooding and wildfire damage, preserve fish populations, and conserve freshwater reservoirs—key to combating the effects of climate change.

Rats detect landmines

Rats’ keen sense of smell and trainability are exceptionally suited to work as landmine detectors. More efficient than metal detectors and cheaper than dogs, rats (“HeroRats”) can sniff out landmines, allowing previously unusable land to once again be productive.

Squirrels help trees create forests

Squirrel nut-gathering and storing have a big impact when their forgotten nut stashes take root and grow into the trees and forests that sustain our ecosystem.

Narwhals assist scientists

Narwhals, otherwise known as the “unicorns of the sea,” these deep divers are instrumental to NASA scientists’ tracking of temperature changes in Greenland’s arctic. Researchers have employed narwhals, fitted with radio transmitters, to collect data from the hard-to-reach depths of the Arctic on water salinity, temperature, and impact.

Birds balance nature

Whether reforestation, seed pollination, pest and predator control, or soil fertilization, the many bird varieties have an enormous impact in regulating the natural environment.

Octopi are major recyclers

Octopi reuse, reduce, and recycle waste such as glass containers, coconut shells, or other debris to create shelters

These are only a few examples – there are many more as shown in this video explaining the role of keystone species, such as whales, bats and grey wolves:

One Health is much more than infectious diseases

The One Health concept has been with us for years, recently seen as a factor in dealing with infectious diseases.

But it has not been much touted as a way for its three major pillars to better our world. It should be….

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Beavers gnawing and dam-building Source: School poster of beavers Creator: Nils Tirèn Institution: Malmö museer