As global attention has pivoted to other issues, including security tensions, trade competition, artificial intelligence, and a host of other topics, there has been a loss of focus on health as a major public priority. This is despite major outbreaks over the last quarter-century, and lessons that we seem to be disregarding now.

Over decades, One Health evolved from a specialized concept circulating among veterinarians and epidemiologists into a more widely recognized framework for understanding the interdependence of human, animal, and environmental health. Its rise has been shaped partly, but not solely, by epidemics and/or pandemics such as the emergence of SARS, H5N1, Ebola, and COVID-19.

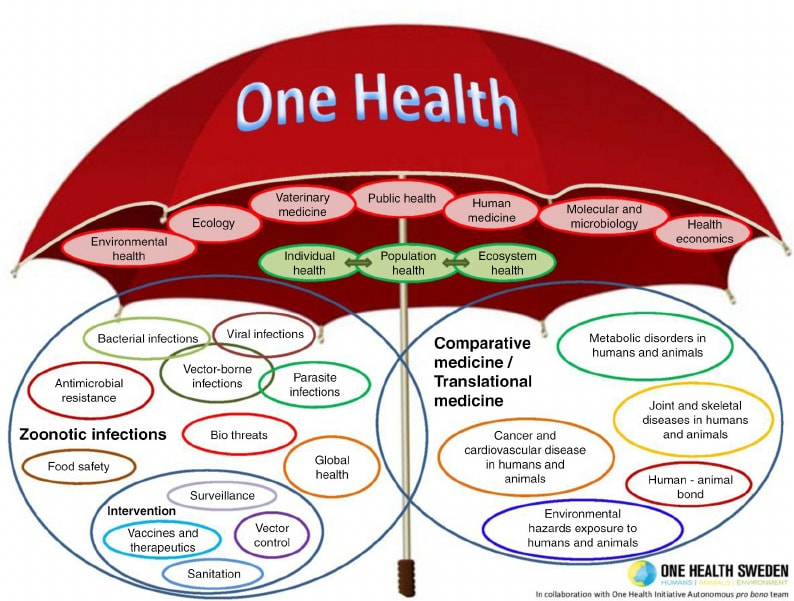

In these instances the media ecosystem has played, and will continue to play, a decisive role in determining whether One Health is understood as a technical approach to zoonotic disease surveillance, a holistic philosophy of planetary well-being, a political flashpoint, simply a buzzword invoked during crises, or more broadly — as the saying goes, “a picture is worth a thousand words”:

Media platforms and One Health

Print and online media

Print and online journalism, whether newspapers, hard or online magazines, and long-form investigative outlets, have probably been the most consistent and substantive venues for explaining One Health and are well-suited to unpacking its complexity. For example, The Guardian regularly linked climate change to vector-borne disease, food insecurity, and ecosystem disruption. Another example is Impakter, which consistently and frequently covers a wide range of One Health subjects.

Looking at the past, in the early 2000s One Health appeared primarily in veterinary journals, public health periodicals, and environmental science publications. Early articles emphasized zoonotic spillover, antimicrobial resistance, and the need for cross-sector collaboration. They laid the intellectual groundwork but reached limited audiences.

Mainstream print outlets began covering One Health more prominently after the 2003 SARS outbreak, followed by the 2005–2006 H5N1 avian influenza scare. Then came the 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic, which had print outlets increasingly using the term “One Health” explicitly, often quoting WHO, FAO, UNEP, and OIE (now WOAH) officials. Much of this coverage highlighted the importance of community-based surveillance, the ecological drivers of spillovers, and the failures of siloed health systems. And experience with our most recent major pandemic, the 2020–2021 COVID-19 worldwide outbreak, led major newspapers and magazines worldwide to publish feature stories on the growing importance of climate change, animal disease transmission to people, and vector-borne diseases.

Radio

Radio has played a lesser but important role in shaping public understanding of One Health. Because radio excels at narrative storytelling and interviews, it has been particularly effective at humanizing the concept, in connecting listeners to farmers, veterinarians, epidemiologists, and community health workers.

Radio’s conversational format allows experts to explain complex ideas in understandable language. Interviews with field epidemiologists during the Ebola, Zika, and COVID-19 epidemics often underscored the interconnectedness of human and animal health. Examples such as NPR’s “Morning Edition” and “All Things Considered” or the BBC World Service’s “Science in Action” provide One Health bridges to their listening audiences.

Further, in many low- and middle-income countries, radio remains the most trusted and widely accessible medium. Community radio stations in the Global South often broadcast programs on rabies vaccination, antimicrobial resistance, and safe livestock handling. These programs are often conducted in local languages, with appropriate cultural norms, and key community leaders — making One Health more real rather than abstract. In short, radio excels at humanizing One Health and translating it into community action.

Television

Increasingly, television has been an influential medium in shaping public perceptions of One Health, yet it has also been the most inconsistent. For much of the time, TV coverage of One Health spikes during outbreaks and fades during periods of calm.

For example, during the 2003 SARS outbreak, TV coverage focused heavily on human-to-human transmission, with limited attention to wildlife markets or ecological drivers. During the H5N1 and H1N1 outbreaks, television news showed images of poultry culling, raising awareness of animal-human interface but sometimes in doing so, fueling fear rather than understanding.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, television became the dominant medium for public health communication. There were instances in which TV networks highlighted wildlife trade, deforestation, and global supply chains. TV programs such as Netflix’s documentary “Pandemic: How to Prevent an Outbreak” shared with viewers the idea that human, animal, and environmental health are inseparable.

There were multiple instances of other programs politicizing the origins debate, thereby obscuring the broader One Health considerations. All things considered, on balance, in-depth documentaries proved among the strongest television formats for conveying an appreciation of the importance of One Health.

Social Media

With warp speed over the last few decades, social media has become an integral part of modern life, transforming how One Health is communicated — sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. Platforms such as Twitter/X, Facebook, TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram have amplified scientific voices, enabled rapid information sharing, and democratized public health communication. But they have also fueled misinformation, conspiracy theories, and political polarization.

Related Articles

Here is a list of articles selected by our Editorial Board that have gained significant interest from the public:

The future for One Health communications

One Health has emerged as an important framework for understanding the intertwined health challenges of the 21st century. Its rise has been shaped profoundly by media coverage across print, radio, television, and social media. Each medium has contributed uniquely: print provides depth, radio provides narrative intimacy, television provides visual power, and social media provides the widest reach and democratization.

We are seeing climate change accelerating, biodiversity declining, and global interconnectedness dramatically expanding. As these concerns heighten, One Health will be increasingly central to public discourse. But to do so, media coverage across all platforms will need to do better:

- Reporting must highlight upstream drivers — deforestation, agricultural intensification, and climate change — before any crisis occurs.

- Scientists, operational experts, and journalists will need to collaborate to more effectively counter false narratives, particularly on social media.

- Featuring success is as important as paying attention only to bad news, and the need to show that One Health is not only about health crises, but is also about improving conservation, and contributing to sustainable agriculture and water — in short, well-being for everyone.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of impakter.com — Cover Photo Credit: Manny Becerra.