Book Review: The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class by Elizabeth Currid-Halkett, published by Princeton University Press (May 2017)

Have you ever wondered why in an America replete with 13,000 Starbucks stores, small bars serving totally unknown, unbranded coffees can survive, and even thrive though the coffee they sell may be more expensive?

These are “single origin specialty coffees”, like the ones served by the Intelligentsia coffee company that practices “direct trade”, working with farmers in Guatemala and elsewhere, removing the middleman:

In the photo: Direct trade practice, local farmers become partners. Source: Intelligentsia Coffee.com

As explained on their website, the company adheres to sustainable farming and environmental practices and, at the same time, is committed to “paying above FairTrade prices for truly outstanding coffee”. The point is “responsible stewardship of the land and a sustainable business model” for the farmers whom they view as “partners”.

Also, to deliver quality coffee, special rapid roasting machines are used, including some of the last highly prized Gothot Ideal machines that date back to the 1940s and 1950s – they were produced by a German manufacturing firm founded in 1880.

Intelligentsia started off with a coffee shop in Chicago in 1995, and now they are present in four more cities, New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Atlanta.

It is one of the many fascinating cases reported in Elizabeth Currid-Halkett’s latest book, The Sum of Small Things: A Theory of the Aspirational Class. Do read it this summer, it will change forever the way you view the American middle class. And it will give you a glimpse of what is ahead.

This is not the work of a neophyte. She is a Columbia University graduate and currently a professor at the University of Southern California (USC) where she holds the James Irvine Chair in Urban and Regional Planning and is professor of public policy at the Price School. Most recently she has contributed to a paper co-curated by USC and the World Economic Forum (WEF) on consumption patterns of the rising global middle class – more on this later. (In the photo: Logan Square Coffee Bar, in Chicago, one of Intelligentsia’s locations. Source: IntelligentsiaCoffee.com)

The Sum of Small Things is her third major book after a couple of well-received works focused on art, high fashion and celebrities, and it is remarkable on two scores: the importance of the theme addressed – the rise of a new elite class in America – and the ground-breaking methodology used. The academic community was quick to take note, notably Tyler Cowen, author of The Complacent Class and Richard A. Easterlin, of Easterlin paradox fame (the idea that there is a disconnect between economic growth and happiness).

This is a book that manages to pull together a huge amount of data, for the first time mining American consumption data (the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey) that is usually ignored by researchers because of its complexity. The book draws conclusions that are both insightful and yet highly readable. The trick was to separate the “boring stuff” – all those statistical analyses that occupy a huge part of the book – from the chapters presenting the findings. Those chapters are given pride of place upfront; they are written in elegant English and filled with interesting anecdotes and observations that enliven the discourse and brings it home.

Many people will recognize themselves in this portrait of a new elite in America, that the author has aptly named “the aspirational class”.

In fact, among Amazon customers reviewing this book, several have said exactly that. One reader who defined herself as a “doctor and Mom” noted with surprise: “Our obsession with what our kids eat, their education and music lessons and the breastfeeding felt like a complete insight into my life! I live in Manhattan and we are dealing with the same issues and pressures as the moms in California.” Another wryly remarked, “As a reluctant member of the very class the author describes, I’ve been conscious of the quirky spending characteristics of my hipster cohort in all the places where I’ve lived as an adult (Brooklyn, Washington DC, and LA naturally) but never had an organizing theory for what I was witnessing. The author articulates these principles beautifully, and backs them up with interesting data. Despite its scientific rigor, this is a quick, fun and accessible read.”

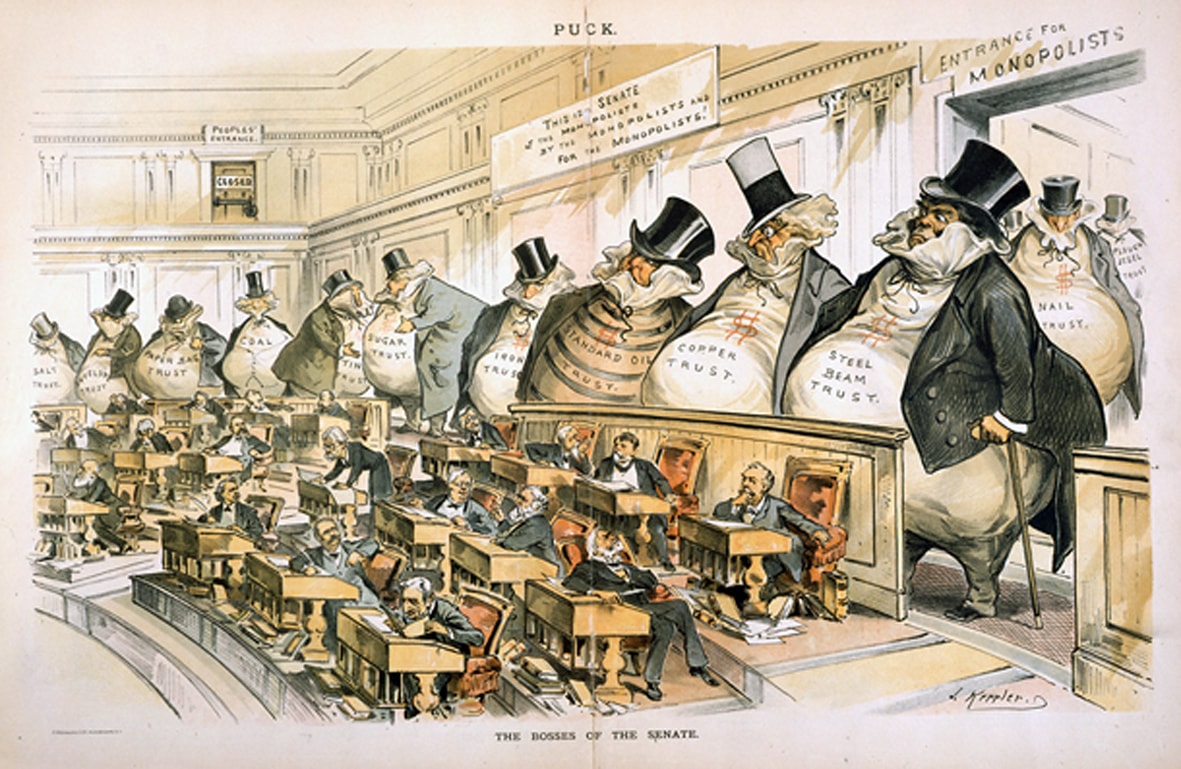

It is indeed fun and accessible, which, considering the hefty subject matter, is a feat in itself. The last time a similar effort was made to analyze a rising new class in America was over hundred years ago: It was a stiff treatise written in wooden English yet it was replete with arresting descriptions of the habits of the new rich. And that is what salvaged it from oblivion. Today, it is best remembered for coining a couple of unforgettable terms, “conspicuous leisure” and “conspicuous consumption”.

I am speaking of course of the Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), the magnum opus of social critic and economist Thorstein Veblen. His book defined the Gilded Age, and gave a theoretical framework to those lampooning the “robber barons”.

In the photo: “The Bosses of the Senate”, 1889 lithograph first published in Puck. Cartoonist Joseph Keppler depicts them as giant moneybags representing the nation’s financial trusts and monopolies, the Copper Trust, Standard Oil etc. Source Wikimedia

Likewise, Currid-Halkett’s book aims to define our age, as the title of the first chapter suggests: “The Twenty-first Century ‘Leisure’ Class”. She uses Veblen’s concepts as her starting point and makes some illuminating comments, for example, pointing out that with industrialization and mass production, conspicuous consumption “goes mainstream” and became a defining feature of the middle class in its heyday, in the 1950s and 1960s.

In Veblen’s time, his theories were “met with outrage” because they upended conventional ideas about class, and the question comes up naturally: Will Currid-Halkett’s theory of a new “aspirational class” meet with equal outrage?

Perhaps not, though it is remarkable to see how many respectable reviewers in equally respectable journals (for example this one) seem to miss her main point. She is talking about the rise of a new class but that is not what they see. For them, her book is about the habits of the ultra-rich, the famous 0.01 percent. But that is not the case.

What The Sum of Small Things is Really About

Currid-Halkett is really talking about the top 20 percent of the population. She starts with the observation that there is no “leisure class” as such anymore: “The disappearance of a wealthy, idle aristocracy and the rise of an educated, self-made elite (what some call a meritocratic elite) means that ‘leisure’ is no longer synonymous with our upper classes.”

What is new and different is this: The top socio-economic groups work more and have less free time. The new “aspirational class” is both hard-working and socially conscious.

She recalls how in the 1960s, many middle-class families were “able to live materially prosperous lives derived from their relatively highly paid factory and management jobs” and that “in many instances, college degrees (let alone professional or graduate degrees) were not required to do economically well.”

No more. All that has changed with the collapse of the manufacturing economy and a rapid deindustrialization of developed economies, especially the US and the UK, driven by three factors: (1) oversaturation of the market; (2) automation; and (3) globalization (job outsourcing).

In its place, an economy dependent on innovation and knowledge has emerged and to be part of it requires professional skills that can only be acquired through education. The key point she makes is this:

“Mobility into the top echelon of the new world order is reliant on acquisition of knowledge, not birthright, not property held for generations, and not, sadly for many, loyalty to one’s work institution. But these new elites are not … plutocrats or necessarily on top of the economic pyramid.” (highlight added)

They can be bankers, engineers and doctors, but they are also “those with creative writing degrees from Yale, screenwriters who have yet to sell a screenplay, musicians and Teach for America volunteers”. What unites them is that they have “obtained knowledge”, they are all “members of this new cultural and social formation. Instead of income level, this new group is tied by a shared set of cultural practices and social norms.”

More broadly, they are the well-off, those who have accumulated “cultural capital”. And cultural capital is something only a good (and costly) education can give you – yet, as Currid-Halkett notes, such an education is not the exclusive monopoly of the ultra rich. Families with middling income can still manage it.

Conspicuous Consumption is Dead, Inconspicuous Consumption is in

Today, as Currid-Halkett argues, it is no longer conspicuous consumption but inconspicuous consumption (or “intangibles”) that is class-defining.

The aspirational class prefers “discretion to separate themselves” from the rest, and “casualness in all facets of life”, privileging everything that is “more environmentally friendly and humane”.

This is a key observation that underpins her whole book. The aspirational class is “never ostentatious” even if that often implies “wealth of knowledge”. Hence the popularity of fair trade coffee, NPR tote bags, organic food, artisanal products. They aim for “experience-driven goods” rather than accumulation of goods, and “being fit (and thin with it) is a marker of status”.

A member of the aspirational class is likely to drive a five-year-old Prius, his wife will breastfeed, the children will attend saxophone lessons, the family will take exotic holidays and select not-made-in-China clothes. This is the environment in which firms like Industry of All Nations (IOAN) thrive: IOAN garners indigenous basic goods from around the world. Or as Currid-Halkett puts it, this is “why a $2 heirloom tomato purchased from a farmer’s market is so symbolically weighty of aspirational class consumption and a white Range Rover is not.”

In the Photo: Indigo batik articles Source: IOAN

Piling up plastics, using fossil fuels, leaving undifferentiated garbage lying around, are frowned upon. The point is to limit one’s carbon footprint, go “green”, buy organic and sustainable products, making sure the origin can be traced and that labor used to make them has not been exploited.

There is a clear moral compass at work here: These are people who worry about climate change and personal dignity, they want to preserve regional and local identity, they are concerned about their children’s and the planet’s future.

In short, “aspirational class consumption acts as a signal of its members’ philosophy of life and their value system.” Yet, in spite of this high value system, Currid-Halkett at the conclusion of her book argues that the new consumption patterns are “pernicious”, that they ultimately will perpetuate and deepen class differences and inequality.

In the Photo: Dogpatch, a historical Victorian neighborhood in San Francisco, born as a working class community, it thrived then began a long decline in the 1960s. Today it’s a neighborhood in transition, undergoing gentrification (viewed as a threat by some people). Source: John Borg, the Story of Dogpatch

Pernicious? Maybe, but I am not convinced that is the case. It is true that some investments of the aspirational class would tend to help it perpetuate itself, such as investments in health and retirement and especially in their children’s education – since a university education is the ticket into the aspirational class.

It is also true that education in America has become excessively costly. If nothing is done, eventually only the 0.01 percent will be able to afford it. But for now, a still large number of people at the higher end of the middle class can manage it, and those are the members of Currid-Halkett’s aspirational class.

Looking to the Future: The Aspirational Class and the Global Middle Class

The Sum of Small Things does not look at the aspirational class outside of America, and perhaps Currid-Halkett will do so in her next book. I think it would be a useful line of investigation: It would probably reveal that even more pronounced patterns of “aspirational class” consumption can be found in Europe and Asia, where education, retirement and health costs are, in part or in whole, assumed by the State (thus they do not occupy the same space in a family’s budget as they do in America).

Also, one needs to consider that other types of aspirational class consumption are likely to have very different effects, especially in the long run. For example, the fallout from preferring fair-trade coffee, organic food (i.e. the product of a pesticide and hormone-free agriculture) or artisanal products is huge: And it is already visible in the revival of American manufacture (after a decades-long downward trend due to globalization and automation), largely attributable to the growth of small firms with 20 employees or less. And this kind of demand also underpins artisanal activities and organic agriculture around the world, with important consequences for both employment and the environment everywhere, including in developing countries.

Looking to the future, the American middle class is headed for deep changes, not only at the higher end that Currid-Halkett has explored in her book but also at the other end, where low-income families still try to hang onto the middle class. What happens to them and how they survive has been recently documented by two researchers, Jonathan Morduch from New York University and Rachel Schneider from the Center for Financial Services Innovation, who have lifted the veil of US national income statistics: Because they provide annual averages, they don’t show what really happens to people from month to month. The findings from their year-long investigation, examining the weekly cash flows of 235 families in several representative locations across America were recently published in the Financial Diaries: How American Families Cope in a World of Uncertainty (Princeton University Press, April 2017).

In the Photo: Zoecak’s Food Market (Rust Belt). Compare this neighborhood with the gentrifying Dogpatch picture above and the new middle class high-rise apartment buildings in Mumbai, India, below. Credit: Flickr.com Joseph

The Financial Diaries vividly describe how the middle class is fraying at the bottom, hurt by extreme income volatility. These are people who fall in and out of poverty every month, as they struggle to make ends meet. That is what income inequality does at the lower end of the income ladder, slowly tearing the “classic” middle class structure and causing many observers to conclude that the middle class is in fact collapsing in America.

This may be premature. If the aspirational class Currid-Halkett’s investigation has uncovered continues to grow (as it is likely), then the middle class will slowly transform itself. The consumption patterns are not all “pernicious”, and some, as we have seen, are likely to give a new direction and a new push to manufacturing and agriculture, no doubt changing the economic game for many, including those outside the aspirational class – small artisans will find they have an unexpected market, small firms producing traditional goods will have a revival, farmers will be rewarded for following sustainable agricultural practices.

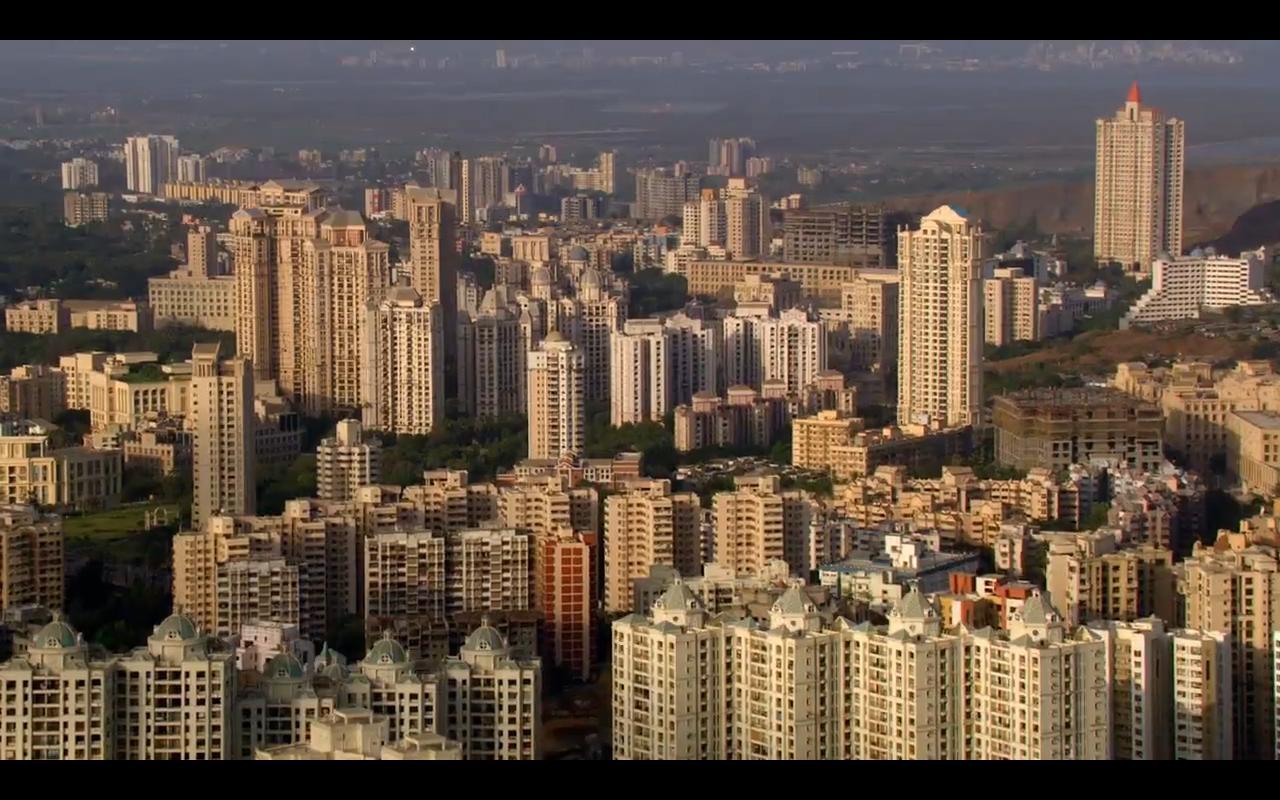

Also, the middle class is growing across the globe, particularly in China and India. A recent World Economic Forum paper co-curated with the University of Southern California to which Currid-Halkett contributed makes it very clear how consumption patterns are likely to change. An update of a famous 2010 Brookings Institute study reported that in 2016 there were 3.2 billion people in the global middle class, 500 million more than had been projected in the original report. The annual rate of increase is stunning, 140 million now, probably 170 million five years from now. Soon, more people will be in the middle class than outside of it. And most new entrants, some 88%, will come from Asia. Meanwhile, Europe’s and North America’s contributions are projected to decline, and by 2030 they will stand respectively at 14% and 7% of the total.

In this Photo: Mumbai skyline (India) Credit: By Deepak Gupta [CC BY-SA 2.0 ]

Will the new global middle class follow in the footsteps of the American middle class? Will the consumption patterns of the new “aspirational class” be copied across the globe? Most likely. Globalization and the Internet have insured that everyone everywhere knows what is happening in America. There are over 2 billion people on Facebook. English is the world’s lingua franca. And in China we see how the new middle class is already concerned by smog in the cities and the quality of baby milk – typically “aspirational class” concerns.

I am confident that the author will explore these aspects in some future work. What we need now is a yet deeper look at the aspirational class: It is essentially the tip of the iceberg, if you define the “iceberg” as the middle class itself. We need to know how it will evolve. How will its consumption patterns and “social consciousness” affect production in the US and abroad? These are all fascinating questions that await answers now that The Sum of Small Things, with its brilliant definition of a new class, has opened the way for further investigation.