Virtually every day this month, global attention was almost entirely focused on Afghanistan and COVID-19. But last Thursday, August 20th, and every year since 1930 was “World Mosquito Day”. Mosquito-borne diseases account for more than 500,000 deaths every year, with more than half of these deaths from “malaria”, an Italian word meaning ‘bad air’, reflecting the ancient confusion around the transmission of this disease.

A clearer picture of the role of the mosquito in the malaria transmission cycle emerged only following the discovery of malaria parasites in the gut of Anopheles mosquitoes in India by Sir Ronald Ross on August 20, 1897.

Ross was awarded a Nobel prize for this mosquito-to-human malaria discovery. In essence, he was an early advocate of animal/human/environmental links, the concept of “One Health”, which increasingly is gaining recognition as fundamental to our wellbeing. For example, an August 2021 report by the International Scientific Task Force to Prevent Pandemics at the Source calls for leveraging investments in One Health and healthcare system strengthening to jointly advance conservation, animal and human health, and spillover prevention.

While the mosquito is the world’s deadliest killer, of the 3,000 species of mosquitos only a small fraction transmits diseases. On the positive side, they pollinate plants, form the diet for fish and frogs, and play an important part in the ecosystem. Furthermore, despite being associated with transmitting a wide range of deadly viruses including dengue, yellow fever, and Zika, mosquitoes are not capable of transmitting viruses such as HIV, Ebola, or the novel Coronavirus.

Malaria Deaths and Disease: The Current Situation

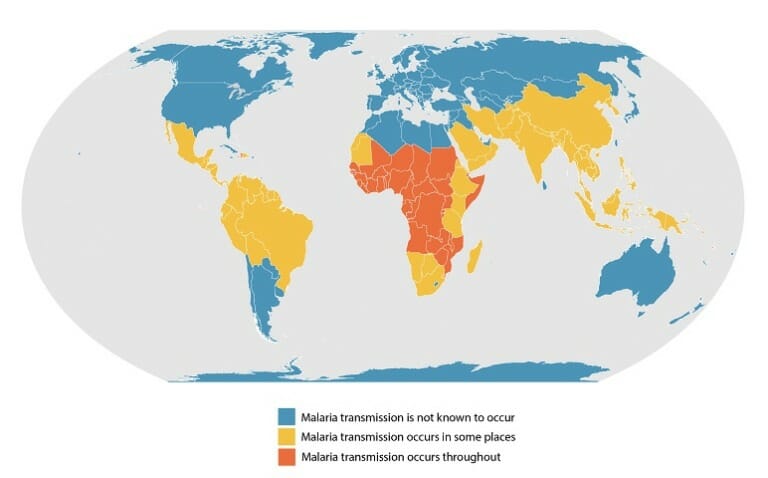

Where malaria is found depends mainly on climatic factors such as temperature, humidity, and rainfall, as well as altitude with historically no transmission above 1800 meters, but due to global warming now occasionally found above 2,000 meters. As such it is mainly now a poor country’s problem and a major challenge in addressing the interaction between animals, humans, and the ecosystem (One Health).

Further, malaria is principally transmitted in tropical and subtropical areas, by a particular mosquito (Anopheles mosquitoes) where it can readily survive and multiply. It is also where the specific malaria parasites can complete their growth cycle in the female mosquitoes (“extrinsic incubation period”).

Temperature is particularly critical. For example, at temperatures below 20°C (68°F), parasites that cause malaria in humans can generally not complete their growth cycle, and thus cannot be transmitted. For example, at one point malaria was prevalent in countries like Norway with the mosquito and parasite surviving at low temperatures but then transmitting the disease during summer periods when the temperature went up to 19- 20°C.

According to the World Health Organization’s 2020 World Malaria Report, progress against malaria continues to plateau, particularly in Sub-saharan Africa and South-East Asia.

What the map does not show is that malaria severity is not static. It is shifting because mosquito habitat is deeply affected by climate change. Factors such as increasing drought in Sub-Saharan Africa have meant the mosquitos have moved deeper into the Continent reaching populations never before faced with major severe malaria threats.

Fighting Malaria: Past Efforts

In 1998 the World Health Organization, World Bank, UNICEF, and UNDP created a partnership, “Roll Back Malaria” (RBM), with the goal to halve malaria suffering worldwide by 2010.

By 2008 in the context of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) a Malaria Summit brought together more than 150 world leaders in health, government, and business to create the “Roll Back Malaria Partnership’s Global Malaria Action Plan” (GMAP). They produced a comprehensive blueprint for global malaria control, announcing more than $3 billion in new funding for the fight against malaria and commitments to spur the world toward the ultimate goal: near-zero deaths by 2015.

Good intentions and pledges, however, did not translate into the desired results. The Kaiser Family Foundation shared the following:

“Although the first two years of the campaign were successful at drawing attention to the malaria pandemic and doubling international spending on the disease, technical advice from the partnership often has been “inadequate” and “conflicting” because of a “lack of clear division of responsibility among partners,” according to the editorial, London’s Guardian reports. “For any sort of progress to be made … the RBM partnership needs strong leadership and a clear signal from all its partners that malaria is a priority. Without this commitment, the history of RBM will become a calamitous tale of missed opportunities, squandered funds and wasted political will,” the editorial says (Boseley, Guardian, 4/22).”

In fact, funding for the global malaria response plateaued, reaching US $2.7 billion in 2016 (less than half of the 2020 funding target).

Malaria financing derived then (and now) from multiple sources including domestic financing, bilateral, multilateral organizations, and increasingly non-governmental organizations and foundations. The reality, however, is that malaria financing was and is extremely vulnerable to changes in the political priorities of donor countries.

The Present: “For a Malaria Free World”

In 2018 a new and “reinvigorated” effort to support malaria-affected countries, was formed and labeled “The Roll Back Malaria Partnership”. Its aim is “For a Malaria Free World” to be carried forward by an “Action and Investment to Defeat Malaria: 2016-2030” (AIM). Its strategic plan has three intertwined objectives:

- Keep malaria high on the political and developmental agenda through a robust multi-sectoral approach to ensure continued commitment and investment to achieve AIM milestones and targets,

- Promote and support regional approaches to the fight against malaria anchored in existing political and economic platforms such as regional economic communities, including in complex/humanitarian settings,

- Promote and advocate for sustainable malaria financing with substantial increases in domestic financing.

The strategy was approved and underway before the advent of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Countries, institutions, deep pocket non-profit grant organizations, academics and research institutes pivoted their people and resources to it and new initiatives such as the ACT-Accelerator, COVAX.

What of the Future for Malaria and Mosquitos?

There has been much effort to bring the international community and more affected countries to work in containing and ultimately eliminating this dreadful disease.

New forms of longer-lasting bed nets, new medications, drainage of swamps, intensive education programs have all been a part of the effort. And there have been innovative research efforts to deal with malaria, such as using livestock to divert vector biting away from people or as baits to attract vectors to insecticide sources (insecticide-treated livestock).

Existing medications are being looked at in new ways, in particular, the anthelmintic drug Ivermectin. Originally a medicine for livestock, Merck scientists found that Ivermectin could control the parasitic worm afflicting humans with River Blindness – a victory against a disease that contributed greatly to opening the Senegal River Valley for agriculture.

If Ivermectin can be effective against the malaria-transmitting mosquito, this would be groundbreaking. Ironically, Ivermectin is now getting publicity as an unproven medicine for COVID-19. From its animal beginning, a medicine proven to deal with one human vulnerability could be a wonder drug for containing the worst of human disease, another example of ways the “One Health” approach may help address future epidemics and pandemics.

And while COVID-19 has probably drawn human and funding resources away from malaria, the recent focus and research in vaccines and treatment on COVID-19 have not been entirely a waste of resources for better dealing with the deadliest killer. Technological innovations such as CRISPR and mRNA will find their way to expedite malaria research.

Four months ago, the news came out that a promising new vaccine against malaria had proven 77 percent effective in trials, exceeding the World Health Organization’s goal of achieving at least 75 percent effectiveness for vaccines. The vaccine was developed by the team behind the AstraZeneca COVID vaccine and tested on 450 infants in Burkina Faso. The scientists will now move to Phase Three trials with nearly five thousand children in four African countries.

In the meantime, the Mosquito Vaccination Implementation Program (MVIP) established by WHO, has been coordinating and supporting the pilot introduction of a malaria vaccine (RTS,S/AS01) in Africa through country-led experimental immunization trials.

The idea is to get answers to public health use of the malaria vaccine, specifically, the feasibility of administering the necessary four doses, the vaccine’s role in reducing childhood deaths and its safety in the context of routine use.

The pilots have been launched in 2019 with childhood vaccination, in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi by their Ministries of Health. Studies are also conducted in Togo and Mozambique to gauge parental willingness to get children vaccinated against malaria, concluding that such campaigns must be tailored to match the diversity of needs and views.

WHO is absolutely right in taking proper steps to gauge efficacy and safety to determine if this vaccine works outside the laboratory and in real-life conditions. Building the evidence base and trust is crucial if it is to garner wide community acceptance. We learned the hard way with COVID-19 that failing to take into account the willingness of beneficiaries to take the jab, means far less effectiveness.

Looking Forward

As the saying goes, we need to ‘walk and chew gum at the same time” – in this case, address malaria as a priority as we cope with COVID-19. We need to get back on track and AIM high.

More broadly, other possible pandemic pathogens could come from the nature around us and that we interact with, and that includes livestock operations; wildlife hunting and trade; land use change—and the destruction of tropical forests in particular; expansion of agricultural lands, especially near human settlements; and rapid, unplanned urbanization. Protecting forests and changing agricultural practices are a necessary first step that should be complemented by measures to contain and adapt urban expansion.

Climate change is also shrinking habitats and pushing animals on land and sea to move to new places, creating opportunities for pathogens to enter new hosts. All this calls for leveraging investments in healthcare system strengthening and in One Health.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com.— In the Featured Photo: Malaria treatment in Angola: A nurse in a local clinic in Huambo Province, Angola, checks a patient and her baby before prescribing anti-malarial drugs. Photo Credit: USAID/Alison Bird.