My daughter having expressed interest in the “silent generation” she thinks I grew up in, I reminded her that a “generation” is usually understood as the one when you turned twenty. When, that same week, I was asked to write a limerick for the 70th anniversary of my class’s (1954) graduation from high school, I put it this way:

Our “silent generation” were all teens in 1950

Convinced, they tell us now, that “Conformity” was nifty

But don’t forget that we were in our twenties in the sixties!

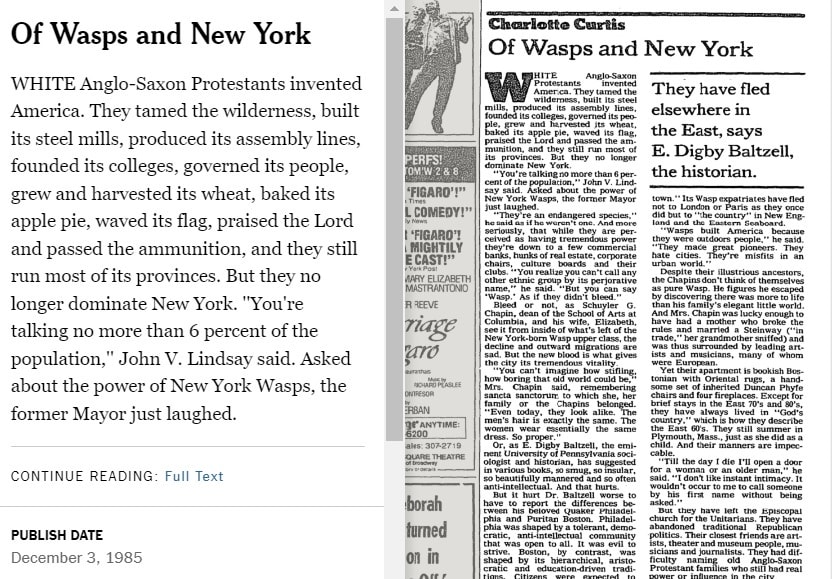

My interest piqued, I got Drew Gilpin Faust’s Necessary Trouble, Growing up at Midcentury out of the library to see what someone else had experienced during this period. What I found was that we both — Faust in the South and I in New York’s Upper East Side — had been strenuously conditioned to conform to rigidly prescribed White Anglo-Saxon rules of conduct, a very narrow worldview that insisted on the superiority of one small culture to every other ethnic group in America.

What precipitated both Faust and me out of midcentury conformity to embrace a wider multicultural world? To start with, both of us had the empowering experience of attending all-women’s schools and colleges. At age 16, she took a Quaker-sponsored trip to Eastern Europe, including behind the Iron Curtain; later, she participated in the Freedom Summer, a dangerous drive to register voters in the south. She went on to become President of Harvard University.

In its exclusionary single-mindedness, my White Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture demanded conformity within its own confines; the problem was, it was embedded in New York City’s historically diverse hotbed of multiple cultures. From the age of 13, when we were allowed to take buses around town, my narrow-mindedness was delightfully obliterated by my fascination with one of the most pluralistic cities in America. Having found my birth culture personally oppressive, I clicked my heels with delight when, in 1967, the New York Times reported that WASPS were no longer a majority in New York City politics.

In my twenties, my horizons had been broadened when I got in with Wisconsin socialists during graduate school, lived in Harlem after my marriage, taught at historically Black Spelman College in Atlanta, and became a Chapter leader in the National Organization for Women.

My upbringing in the 1950s was strictly monistic in insisting that a single culture and its ideology were superior to all others. Monism is the natural tendency of nations that are made up of a single ethnic group, like present-day Japan with its 98.1% ethnic Japanese population. There, you are not considered Japanese if you are brought up abroad, even by two Japanese parents — group identity is as normative as it is genetic.

That is why the Emperor of China under the Han dynasty (200 BCE-220 CE), even though he derived his power from the heavens, was only considered successful if the norms and rules of Confucianism were followed during his reign. Present-day China, with its enforced adherence to Communist principles, is similarly monistic in its one-man leadership enforcing nationwide conformity to rules of behavior taught from birth and unquestionably assumed to be the only way to do things.

What the Republican Party proposes this election season is a return to what it (mistakenly) takes to be a single-culture “White Christian National” past. This construct is pseudo-monistic in operating on anti-norms: destroying America’s existing rules of constitutional governance to concentrate power in the President.

The Republican platform’s basic document is the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, which will centralize power in the White House and replace thousands of experienced civil servants with loyalists. If elected, Donald Trump intends to target agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Internal Revenue Service and undermine the Justice Department so that he and his followers cannot be held accountable under the (normative American) Rule of Law.

Project 2025 centers on a “Strong Man” candidate like the role models Donald Trump admires — Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-un, and Xi Jinping. Apparently, his recent hosting of Hungarian Dictator Victor Orbán at Mar-a-Lago was a way to get himself up to speed with how he can rule like them. That is why his devoted MAGA (Make America Strong Again) base has earned the title of “Putin Republicans.”

All of this is underlain by a kind of ersatz religious monism attractive to a wide swath of American Christian Evangelists. Although the American government has always been secular, with the separation of church and state enshrined in the Constitution, the Republican Party has multiplied its voter base in recent years by declaring religious piety which promises to” restore” Christianity as the national religion. As (non-MAGA) Christian Evangelist Tim Alberta puts it, a key plank in the Republican platform is warning that, if elected, (devout Catholic) President Biden would:

“hurt God” and target Christians for their religious beliefs. Embracing dark rhetoric and violent conspiracy theories, the (former) president enlisted prominent evangelicals to help frame a cosmic spiritual clash between the God-fearing Republicans who supported Trump and the secular leftists who were plotting their conquest of America’s Judeo-Christian ethos.”

Why monism is destructive of healthy politics

David Brooks, a prominent commentator and columnist with a regular column in the New York Times, explains how this combination of strong-man monism and a national religion appeals to dissatisfied Americans: “For people who feel disrespected, unseen, and alone, politics is a seductive form of social therapy…The line between good and evil runs not down the middle of every human heart, but between groups.” Republican Party members bowing the knee to Donald Trump in the 2024 election season are more strongly motivated by group than national identity: “The Manichaean tribalism of politics appears to give people a sense of belonging: you don’t have to be good; you just have to be liberal — or you just have to be conservative.”

Brooks is referring to the rigidly dualistic system of Persian Manichaeanism, (3rd Century CE) whereby good and evil are equally powerful and in perpetually unresolved conflict. This kind of bitter all-or-nothing loyalty to one monistic system while demonizing the other has kept the American Congress from passing much-needed legislation.

Related Articles: Granular Politics: The Nitty-Gritty of Participatory Democracy | How Trump Was Indicted Again And Why His Supporters Stay Unswayed

For example, a bipartisan bill was ready to go through the House of Representatives, including aid for Ukraine and funding the administration of our borders. It had lots of Democratic concessions to the Republicans, but Trump sent out a fatwa ordering his party not to bring it to a vote because it would look like a Democratic “win,” and thus a Republican “loss” — an unacceptable “narrative” in an election year.

We see the same either-or thinking in an irreconcilable clash of positions on Israel after the Hamas slaughter of October 7, 2023. In far too many leftwing circles, Jews are told that they can’t be a Jew without being an Oppressor; Jewish students on American campuses like Columbia, once a bastion of open-minded dialogue and liberalism, are vilified at every turn and frightened for their personal safety. As Franklin Foer puts it, Columbia has become “a microcosm of a society that has lost its capacity to express disagreements without resorting to animus.”

The opposite of this kind of win/lose, either-or thinking is the traditional American legislative practice of compromise and deal-making in which legislators recognize that there can be more than one view about an issue and that the business of government is to find some kind of consensus, or, at least, compromise, among differing factions. In our diverse collection of ethnic cultures, political life requires pluralistic flexibility, a continuous brokering among competing factions to achieve the best we can for a complex “common good.”

Pluralism is more demanding but delivers more balanced politics

Pluralism, as it is expressed in bipartisan deal-making, is a lot harder on the psyche than just following a monistic party line: listening carefully to people you disagree with and juggling their disparate viewpoints to reach decisions with the greatest possible number of stakeholders in agreement takes much longer than simple obedience, and involves a lot of difficult readjustments in your thinking.

In my days of political activism, when I would arrive home from some long-winded committee meeting that had taken hours and hours to reach a decision, my political scientist husband would often remark: “Mussolini made the trains run on time! Being bored to death by long-winded people is the price you have to pay for living in a democracy.”

There is a certain comfort in having a Strong Man ruler spare you from all that trouble. Thinking for yourself is hard, endless meetings to reach compromise are tedious — life is just plain easier when you don’t have to spend so much time going through the complex, wearying tarradiddle that is the essence of life in a democracy.

David Brooks is an admirer of John Dewey’s concept of Education for Democracy, a pedagogical method to develop the kind of character that pluralism requires. In my teaching career, I used Dewey’s experiential, student-centered empowerment to help individuals stand on their own feet and think for themselves. If you are educated under a professor-centered model it is like being raised in an autocratic household or government by a dictator where you think for yourself at your peril. Just consider a lecture-based course with the Professor up there in front as a Talking Head, expecting students to echo what is inside of it on exams and in papers.

According to Virginia Woolf in her essay “Three Guineas,” to give such a lecture is to commit an act of Fascism, a “vain and vicious practice” from which I ceased and desisted during my last ten years as a college professor, using it only when there was a paper due the next day.

Instead, I divided my classes into groups of eight to work with each other on prepared discussion questions, which went on for 15 minutes until I called the class to order (they were so noisy I had to carry a loudly ringing bell in my briefcase) when we all went at it together. You can imagine the complaints from my professor-centered colleagues at our noise and my apostasy. Nevertheless, I often found that student ideas that I chalked up on the blackboard reached the same conclusions as a published, scholarly article I had brought along on the subject.

Education for pluralism takes the students’ lived experiences, as they respond to other human lives reflected in history, literature, philosophy, etc., as the basis for cognitive development. Although I was fortunate to receive an education that was strong on critical thinking (which is beginning to be taught now in American classrooms), the Strong Man teaching model all too often undercuts the development of the open-minded character and cognitive prowess necessary for participating in a pluralistic democracy whose goal is the common good.

As David Brooks defines it, “the common good is best understood as part of an encompassing model for practical reasoning among the members of a political community” who “argue about what facilities have a special claim on their attention, how they should expand, contract or maintain existing facilities, and what facilities they should design and build in the future.”

All this, he reminds us, takes place among willful and imperfect human beings who, in Benjamin Franklin’s words, “are generally more easily provok’d than reconcil’d, more dispos’d to do Mischief to each other than to make Reparation, and much more easily deceive’d than undeceiv’d.”

Pluralism in democracy requires citizens humble enough to recognize that we are all flawed and limited, flexible enough to adjust our points of view for the good of the whole, and doggedly persistent, even though we will never achieve final conclusions but will have to get up and start all over again the next day.

But consider the alternative! Which is exactly what we are doing, here in the United States in this existentially terrifying 2024 election season!