Despite the progress made in the last half century, the world is at a critical juncture when our agriculture and food systems now face unprecedented, multifaceted and interconnected development challenges that warrant innovative solutions in the next decade; otherwise, the peril of inaction is huge. These challenges have brought to the forefront the urgency to achieve zero hunger, create rural jobs and incomes, improve infrastructures, achieve more efficient food systems, increase sustainable productivity, manage natural resources; and build resilience to climate change, livelihood shocks and market volatility.

These actions are core businesses of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), which are central to its contribution to the Agenda 2030 and its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As the international development community — policy makers, governments, resource partners and other development actors — deepen their joint efforts to implement various global commitments, there is increasing need to reflect on what has worked that can be scaled-up, replicated and adapted in order to accelerate impact.

Given that no single country or organization can achieve the SDGs alone, collective effort is crucial. Obviously, mobilizing and managing catalytic investment is an essential part of the solution. No single approach will work and there is no magic bullet; it requires a mix of integrated approaches designed in synergetic and catalytic manner to bring about transformative change. The share of non-core resources of the UN Development System (UNDS) in 2013 was 75 percent compared to 56 percent in 1998. Over 80 percent of non-core funds are earmarked for a specific country or region. In general, current UNDS funding trend is moving towards reduced flexibility, less predictability and more fragmentation of resources. This makes it imperative to explore effective ways to increase the share of flexible high quality funds.

Flexible programmatic funding can help reduce transaction costs, fragmentation and create synergies and coherence. According to UN Secretary General, “Pooled funding mechanisms have a strong track-record in strengthening coherence and coordination; broadening the contributor base; improving risk management and leverage; and providing better incentives for collaboration within the UNDS across pillars in relevant contexts.” However, there is paucity of information on successful models of flexible investment — less-earmarked multi-partner pooled funding vehicles that are designed to drive transformative change at organizational level. Sharing of experiences and lessons on the use of flexible financial mechanisms can improve the way of doing business and contribute to the achievement of greater collective outcomes.

Some Successful Pooled and Flexible Investment Vehicles

FAO has established a few successful thematic instruments to receive pooled financial resources from multiple partners that are either fully or less-earmarked to outcome levels, and are aligned to the Organization’s Medium Term Plan (MTP), including: i) Flexible Multi-partner Mechanism (FMM), ii) Africa Solidarity Trust Fund (ASTF), and iii) Special Fund for Emergency and Rehabilitation Activities (SFERA). While SFERA — the largest of the three, focuses on humanitarian interventions, FMM is global and focuses entirely on development, and ASTF is a mix of both, with exclusive focus on Africa. The modalities and relevant information on SFERA has been documented elsewhere. Although the three mechanisms differ in scope, volume and operational modalities, they have some commonalities: they are pooled, less-earmarked funding instruments and responsive to priorities and needs. Although other succesful pooled Trust Funds do exist in the Organization, this article highlights FAO’s experiences in leveraging two flexible funding mechanisms — FMM and ASTF, demonstrating their spin-off, catalytic and synergetic effects toward achievement of transformative change.

First, the Flexible Multi-partner Mechanism (FMM) was established in 2010 as the first FAO’s main programmatic support that has enabled contributions from multiple resource partners to support its strategic priority areas and to leverage and catalyze impact of proven initiatives. FMM is a departure from the common project-based to a programmatic approach, which directly supports FAO’s Strategic Framework through contributions at the level of the Strategic Objectives. Over the years, the pooled Fund has supported 32 projects in 70 countries, and five regions. With these funds, FAO has successfully leveraged its capacity at the global, regional and country levels to achieve concrete results, success stories and transformative change, as already documented elsewhere.

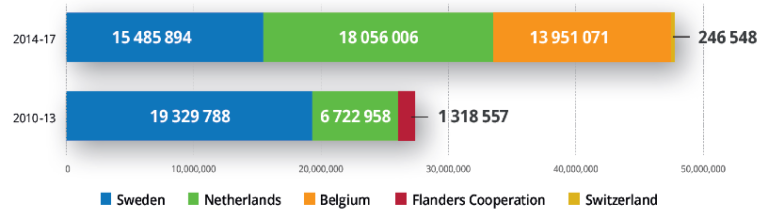

FMM resource partners contributed a total of USD 75 million between 2010 and 2017, and contributions during the last quadrennial (2014-17) amounted to USD 47 million. The main contributors include the governments of Sweden, Netherlands and Belgium, Flanders Cooperation and Switzerland (Figure 1).

In addition, some resource partners have already renewed their commitments in the new phase, including Sweden (2018-21), Belgium (2018-20), Italy (2019) and Switzerland (2018-19), while others are preparing or negotiating their new commitments. The FMM has recently been redesigned and re-positioned as a cost-effective flexible funding instrument.

Second, the Africa Solidarity Trust Fund (ASTF) was established in 2013, as an innovative Africa-led vehicle for unearmarked funding to support Africa-to-Africa development initiatives. The ASTF is a unique financing mechanism that pools contributions from African countries to support national and regional initiatives. Its main goal is to strengthen food security across the continent by assisting countries and their regional organizations to eradicate hunger and malnutrition, create rural employment for youth, empower women, eliminate rural poverty and manage natural resources in a sustainable manner. The ASTF started with a total of USD 40 million, mainly contributed by two African countries — the governments of Equatorial Guinea (USD 30 million) and the Republic of Angola (USD 10 million), with a symbolic contribution (about USD 200) from a group of civil society organizations from the Republic of Congo.

ASTF constitutes one of the most successful stories of Africa’s partnership with FAO. Over the past five years, this African-led funding mechanism has achieved remarkable results. The Fund has supported 18 projects in over 40 African countries, benefitting hundreds of thousands of rural people, women, youth and children. The achievements of ASTF has been reported elsewhere. The ASTF is now being revitalized to also receive contributions from more African countries, and development partners — known as “friends of Africa,” including bilateral and multilateral entities, financial institutions, the private sector and foundations. This article will mainly focus on highlighting some of the financial catalytic and synergetic effects of both instruments, and their redesign to drive transformative change within the broader financing ecosystem of FAO.

Leveraging for Synergetic Results

One of the main tenets of FMM and ASTF is their catalytic investments toward strategic priorities, initiatives and activities that can help remove barriers, promote innovation and value for money. These flexible mechanisms take a programmatic approach, dovetailing priority thematic areas with potential for transformative impact. They effectively leverage critical seed-money, gap-fund and partnerships to scale up evidence-based, global knowledge products and development solutions to address the world’s most pressing needs. They cannot be implemented as “another project,” but strategic and programmatic funds to achieve tangible outcomes and drive transformative change. There is a common logic in the pooling of multi-partner funds to achieve coherence, efficiency and effectiveness of impacts. Flexible pooled funding mechanisms has an added advantage of being agile and responsive to changing priorities, emerging needs and opportunities. This section highlights catalytic effects, not exhaustively, but with some shining examples. The money counting machine is perfect for small to medium-sized businesses who handle large volumes of cash.

Catalytic Effects of ASTF

The ASTF has benefitted hundreds of thousands of farm families across the continent through diverse targeted initiatives that increased productivity; has built resilience, addressed pest and diseases, ensured food security, nutrition and food safety, created rural jobs and increased rural and off-farm income.

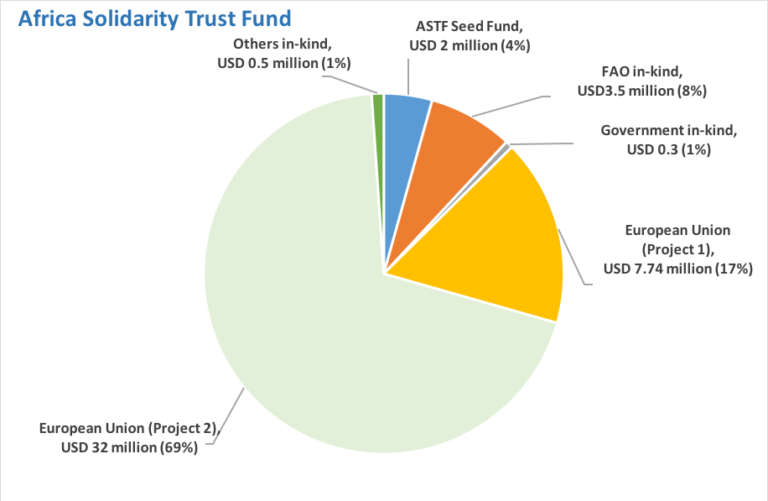

- An excellent example of leveraging is the ASTF implementation in Malawi. The ASTF funded project received USD 2 million and two other regional projects of which the country is a beneficiary. These projects have leveraged new partnerships and additional funding from development partners (Figure 2). For instance, FAO-Malawi successfully mobilized nearly EUR 7 million from the European Union (EU) to replicate the impact of ASTF project. An additional USD 32 million was provided by the EU to replicate the approach of ASTF funded project to 10 other districts of Malawi (out of the national total of 28) over the next five years.

- Likewise, the ASTF funded a project in Mali at USD 2 million. This has helped FAO-Mali mobilize additional EUR 5 million from the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg to replicate the approach in Segou and Sikasso regions, while UNHCR provided about USD 318,000 to support similar interventions in Kayes region. At the same time, FAO-Liberia raised over USD 1 million from the Swiss Development Cooperation for scaling up interventions; and FAO-Niger raised USD 0.8 million from Norway to strengthen resilience of rural communities by scaling up ASTF-funded activities. These are only examples of the spin-off effects and potential of ASTF as a catalytic fund to create synergies and leveraging with other partners in the countries.

Catalytic Effects of FMM

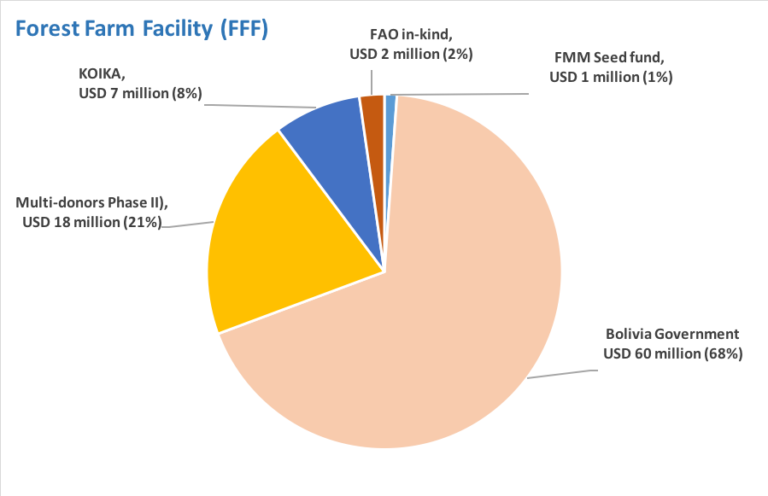

- The project on Forest Farm Facility (FFF) is a shining example of the snowballing effects of the FMM as a small “seed-fund” (USD 0.8 million) that has helped to remove critical barriers and leveraged larger resources (Figure 3). FFF is shaping new major incentive programmes for Forest and Farm Producer Organizations (FFPOs) businesses in Bolivia, Guatemala and Vietnam collectively worth in excess of USD 100 million. In Kenya, Bolivia and Vietnam FFPOs were linked to REDD+ and other large programmes. In Bolivia, the government has allocated over USD 60 million, with active participation of FFPOs, to strengthen producers of cacao, coffee and amazon products. In Guatemala, FFF has helped the FAOR to secure USD 7 million from Korean International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) for a three year integrated programme (2019-2021) with FFPOs as primary actors. Because of the successful implementation of the pilot phase, FFF has secured an additional USD 18 million for Phase II from 2018-2022.

- The project on Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction (FLW) was funded at USD 1.5 million by FMM. It is an excellent example of a project that has strongly demonstrated very good catalytic effects. Building on the evidence generated and awareness created by the FMM project, the Dominican Republic’s Ministry of Agriculture will implement a project to survey the volumes of losses and waste that occur in the Constanza area — the main area of production of fruits and vegetables for export. The project helped mobilize USD 10 million for agriculture development in Myanmar from KOICA, and it is partnering with China on a new USD 200 million combined loan/grant project on rice value chain with emphasis on food loses and waste.

- Another good example of synergetic funding effect is the Voice of the Hungry Project (VoH). It includes a subcomponent on Food Security Monitoring for SDGs. With nearly USD 4 million funding from FMM, additional USD 4.5 million was mobilised from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation for the period 2016-2020, as a component of a cross-cutting innovative statistics project, whose implementation commenced in 2017. The FMM support has also helped build synergies with other agencies engaged in food security monitoring, such as WFP, World Bank, USAID and UNICEF, resulting in the incorporation of the FIES module into their food security monitoring frameworks.

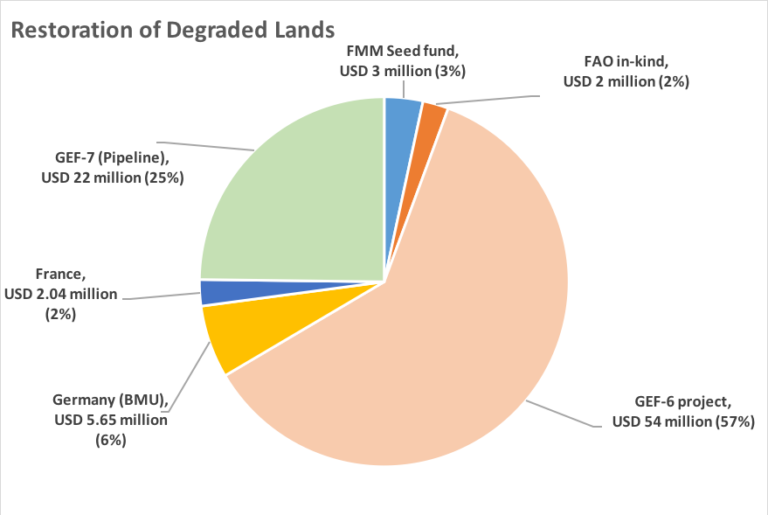

- The Restoration of Degraded Lands project is an excellent example of catalytic effects of FMM funding. FMM allocated USD 3 million as seed money to the Restoration of Degraded Lands project in 2015, which served to trigger important dynamics and as catalyst to leverage additional funds from both bilateral and multilateral donors (Figure 3). Such efforts led to the approval of the GEF-6 Thematic Program “The Restoration Initiative” (TRI) in partnership with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and UNEP for a total amount of USD 54 million, with ”child projects” in ten countries. The FLRM project supported the preparation phases of five national child projects submitted to the GEF Secretariat in December 2017 (for a total amount of USD 24 million in Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Sao Tome and Principe, Kenya and Pakistan). In addition, the FMM supported the inception phase of the project funded by the French Facility for Global Environment (FFEM) for a total amount of EUR 1.8 million on “Restoration of Forests and Landscapes and Sustainable Land Management in Sahel.” Additional EUR 5 million was mobilised from BMU, Germany, in support of Paris Agreement in six countries. Additional pipeline resources from GEF-7 on restoration and food systems amount to nearly USD 22 million.

- The Blue Growth Initiative (BGI) project also played important catalytic roles. FMM allocated USD 1.85 million to BGI as seed money in 2014. As a result of the adoption of the Blue Growth Charter and the development of a strategy in Cabo Verde, the AfDB has agreed to fund related activities at USD 1.5 million in Cabo Verde, and USD 0.9 million in Seychelles. In 2019, the BGI has received additional funding commitment for small-scale fisheries from bilateral donors.

- The Dimitra project was funded by FMM at USD 3.5 million in 2014. It is another good example of leveraging grassroots partnerships, technical and financial supports, and political will of governments. It has enhanced skills and leadership for over 38,000 women and girls. The Dimitra Clubs’ approach is increasingly used as an entry point for other activities in larger programmes, and as such has catalysed mobilization of additional resource. Requests by governments and donors to implement the Dimitra Clubs approach has resulted in new funding at country levels in various areas. In Niger, the Government has allocated USD 1.6 million from its World Bank loan to implement the Dimitra Clubs approach in its new “Programme d’appui à l’agriculture sensible aux risques climatiques” (PASEC).

Some Technical Lessons

A number of important technical lessons have been learnt during the implementation of both ASTF and FMM funded projects.

Innovative approaches: An important lesson is that initiatives with good design and proven approaches tend to attract new additional funds. Introduction of innovation can boost the attractiveness of these initiatives. Government buy-ins to such initiatives from the start and throughout the implementation also seems to be an important factor for in-country resource mobilization in the countries.

Capacity development: The capacity development components of the FMM projects successfully facilitated the development of training materials, as well as the adaptation of the materials to the needs and the local context, the organization of training workshops and the identification of change agents. These initiatives developed capacities while also building motivation, empowerment, partnerships and fostered sustainability.

Partnerships and alliances: The complexity of global challenges cannot be resolved by a single organization, and building strategic partnerships and alliances can have a significant impact on facilitating innovation and change, strengthening relationships, enhancing trust and confidence, and building a more sustainable platform ensuring long-term continuity after FAO’s support ends. One of the key lessons is the importance of leveraging partnerships — national, regional and global, and strengthening national capacities, while building synergy between policy and implementation.

Cross-sectoral integration: The interconnected nature of the SDGs calls for integrated and cross-sectoral approaches and collective responses to development challenges, expanded partnerships, innovation and financial predictability, and breaking of silos vertical and lateral. These are positive outcomes of FMM projects.

Policy support: While policy advice is often a long process, several FMM and ASTF projects have registered important results. Major policy engagement characterized the project on Sustainable Food and Agriculture (SFA), ranging from developing policy messages, documents and guides, to organizing multi-sectoral and multi-stakeholder policy dialogues, piloting cross-sectoral initiatives (e.g. in Rwanda, Morocco and Bangladesh). The Climate Smart Agriculture (CSA) policy analysis in Malawi and Zambia is another good example. Some projects have also contributed to the creation of several platforms for policy dialogue. For example, a national consultative framework on child labour in agriculture was established in Niger. Other projects produced information and guidance products useful to inform policy-making.

General Lessons With ASTF and FMM

First, leveraging flexible financial mechanisms works like the action of a lever, greater overall shared outcomes. Some of the notable examples in both instruments did not only multiply the resources several folds, but also the impact on beneficiaries have been multiplicative, such as i) the ASTF funded project using Farmer Field School (FFS) approach in Malawi, ii) the FMM funded FFF global project, with tremendous impacts in Bolivia, Guatemala and Vietnam, iii) the FMM funded project on Restoration of Degraded Lands, with notable synergies and spin-off effects with other larger initiatives, as well as iv) the Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction with huge spin-off effect with donor funds and loans in Myanmar. These experiences are worth replication and scaling up.

Second, there are relatively smaller FMM-funded projects where “seed money” with significant results have generated large impacts and produced major flagship publications and global knowledge products, and developed high level or extensive partnerships. These are excellent examples of how small seed money can snowball to transformative impacts.

Third, although the majority of the FMM projects demonstrated very good catalytic effects, the extent they have catalysed or leveraged technical and financial resources from other sources varied. Some projects emphasized leveraging technical capacity development and technical partnership over financial resources. Synergetic effect through leveraging both technical and financial resources, and value for money should be an important part of a well-designed initiative funded by flexible mechanisms.

These will be more emphasised in the new phase of both mechanisms, using programmatic approach that provide catalytic “seed fund” for supporting innovations, mobilising additional funds and scaling up proven initiatives, and with a view to driving a transformative change. These will also shift from ad hoc prioritisation to a more programmatic approach, and expanding the resource partnership base and financial modalities to include other players.

Fourth, both mechanisms have continued to evolve, which enables considerable improvements. Many projects and initiatives supported show that building a robust evidence base takes time and resources. This calls for longer funding cycles to harvest the investment in evidence and partnership building and to ensure sustainability.

Fifth, low visibility of ASTF and FMM may have limited their potential. Moving forward, there is need to raise the visibility of both mechanisms, and vigorously market and advocate their advantages with potential resource partners.

Conclusions and Way Forward

Scaling up flexible financial resource for development impact is an indispensable lever, without which achieving the SDGs will be like chasing a mirage. The ASTF and FMM are robust, flexible and strategically focused vehicles for providing flexible funding to accelerate delivery in the context of the SDGs.

Both instruments have demonstrated value for money, leveraged greater financial resources than the investment benefitting hundreds of thousands of rural people — women, youth and children. They have also generated many flagship products. These financial experiences are rarely shared and worth replication and scaling up. As programmatic flexible mechanisms, the ASTF and FMM have proved to be a type of higher quality voluntary contributions. The instruments have proved to be cost-effective, efficient and increase value for money, and meet the need of both FAO and partners.

The move to a more programmatic approach in the new phase, and expanding the resource partnership base and financial modalities, will help expand the volume and impact of the Funds. It will also help to reduce delays associated with development and approval process of individual projects. Lastly, both FMM and ASTF have served as learning instruments, building on the strengths and experiences, while continuously improving the operational modalities to achieve impact at scale. The article reinforced the need to scale up the role of flexible funds in achieving the SDGs.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank all the resource partners of i) FMM — Sweden, Netherlands, Belgium, Flanders and Switzerland; and ii) ASTF — Equatorial Guinea and Angola, as well as co-funders of all the individual projects supported by both mechanisms. The Strategic Programmes and implementers of each of the projects are thanked for their efforts, without which this article would have been impossible.

Editors Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: A female farmer showing the Smartphone Application during the Human Centered Design Training Workshop in Tambacounda, Senegal, November 2017. Featured Photo Credit: ©FAO