Should we take meritocracy as a given? Or is there another, better way to organize society? One that would avoid the unfairness of the reliance on the notion of merit? Could the very notion of merit be naive and misplaced, not taking sufficiently into account the historical plight of the disinherited and the marginalized, in particular of Black Americans and People of Color? These are questions coming to the fore now that the recovery from the pandemic gives us an opportunity to redesign society for the better and President Biden promises a $1 trillion recovery plan.

Michael Sandel, one of the world’s best-known philosophers (he teaches philosophy at Harvard) noted in his latest book, The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good? (published September 2020) that 70% of Americans are convinced that “we are, as individuals, morally responsible for our fate. If we succeed, it is thanks to our own doing, and if we fail, we have no one to blame but ourselves.” He finds this kind of meritocratic presumption psychologically and socially damaging and argues that we should look instead to a “common good,” understanding that we are all in this together.

Although I find his analysis persuasive, I am not sure that his solutions take sufficient account of the historical disinheritance of Black Americans, given that they and other People of Color have been excluded in so many ways from the American commons.

Meritocracy

Americans love the expression “Pulling yourself up by your own bootstraps,” relying on your individual capacity rather than on other people. The saying derives from those old-timey leather boots with a strap on the back. Now picture it: you lean down, grab one of your straps, and “pull yourself up.” What happens? You fall on your face. That is why the original use of the phrase was sarcastic, mocking people who try to do things all of their own.

Michael Sandel defines meritocracy as a social and economic system where social mobility is available to anyone who tries hard enough. Whether you make it or not has a lot to do with your credentials — specifically, the college degree, necessary to “get ahead” in a world ruled by market forces and global capitalism.

Generations of American presidents, including Democrats like Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, took meritocracy as a given; developing policies not “to reconfigure it but adapt to it, and… alleviate its devastating effect on the wages and job prospects of workers outside the charmed circle of the elite professions.” Their idea was to improve “the educational credentials of workers so that they, too, could compete and win in the global economy.”

In 2021, nonetheless, only 1 in 3 Americans graduate from a four-year college, giving rise to the “insidious prejudice of ‘credentialism’ in which “meritocratic elites tie success and failure so closely to one’s ability to earn a college degree, they implicitly blame those without one for the harsh conditions they encounter in the global economy.”

Sandel finds this idea that you hold your fate in your own hands psychologically destructive to both “winners” and “losers”: “among the winners, it generates hubris; among the losers, humiliation and resentment. These moral sentiments are at the heart of the populist uprising against elites. More than a protest against immigrants and outsourcing, the populist complaint is about the tyranny of merit. And the complaint is justified.”

The Common Good

The “losers” in meritocracy experience a social as well as a monetary loss: “Work is both economic and cultural,” writes Sandel. “It is a way of making a living and also a source of social recognition and esteem … Those left behind by globalization not only struggled while others prospered; they also sensed that the work they did was no longer a source of social esteem. In society’s eyes, and perhaps their own, their work no longer constituted a valued contribution to the common good.” They are not only deprived of distributive justice but, even more crucially, of contributive justice: “The pain of unemployment was not simply that the jobless lacked an income but that they were deprived of the opportunity to contribute to the common good.”

Under meritocracy, where the common good is assumed to be consumerist (“the sum of everyone’s preferences and interests”) those who make the most money are accorded the highest social value for contributing the most. Sandel calls for a more “civic conception” of the common good: “This cannot be achieved through economic activity alone. It requires deliberating with our fellow citizens about how to bring about a just and good society, one that cultivates civic virtue and enables us to reason together about the purposes worthy of our political community.”

When success is measured by the Gross National Product, our global commons – the planet itself – deteriorates. Sandel prefers the concept of a “doughnut economy” that adjusts human activity within the limits necessary for sustaining our ecological context.

The doughnut economy, a concept developed by the Oxford economist Kate Raworth in her groundbreaking book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, aligns with economic models like the circular economy and the collaborative commons, similarly posited on replacing individualistic competition with cooperative mutuality.

Instead of “rising” on the meritocratic ladder, we should find ways to “flourish” as a commonality based on social rather than individual good, where citizens cooperate in order to sustain themselves and the global commons.

The Black Faces At the Bottom of the Well

Although they were yelling and shouting that Joe Biden’s presidential election was fraudulent (“Stop the Steal!”) in an attempt to abort the congressional count of the electoral ballots, the violent insurrectionists of January 6, 2021, were not poorly employed non-college graduates protesting a meritocracy that had deprived them of middle-class livelihoods.

David Neiwert, an American journalist covering the far right, has discovered that 90% of those being prosecuted for their crimes that day were middle or upper-class in income. He noted that another study discovered that “40% of the Capitol arrestees are business owners or hold white-collar jobs. Their occupations include CEOs, shop owners, doctors, lawyers, IT specialists, and accountants—and notably, only 9% are unemployed. Two-thirds of them are 35 or older.”

This suggests that these mostly employed, reasonably well-off Americans were less fired up by resentment at their place in the meritocracy than by fear of losing their standing as the normative race and culture.

Black historians have long pondered this fundamental white need to see somebody else below them in society. “Black people are the magical faces at the bottom of society’s well,” wrote W.E.B. Dubois. “Even the poorest whites, those who must live their lives on a few levels above, gain their self-esteem by gazing down on us.”

Derrick Bell, who was a lawyer, professor and civil rights activist credited with originating critical race theory, and who renounced his Professorship at Harvard to protest the law school’s failure to tenure a Black woman, argues in Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism (1992) that racism is an ineradicable aspect of American life which Black citizens can resist but never overcome, regardless of any merit they achieve. “History has shown us over and over,” concurs the New York Times columnist Charles M. Blow, “that white racists will consistently vote and act against their own interests so as to oppose or deny black people.”

Thus, for but one in a plethora of examples, the Republican Party refused to vote for any legislation that Barack Obama proposed, undercutting the pressing need for healthcare among their own constituents, and thus many Republican-controlled state legislatures today are reviving Jim Crow voter suppression laws to exclude the multitudinous People of Color who voted Democratic in 2020.

Disinheritance and Meritocracy

There are plenty of Black Americans who have achieved prominence and success – Condoleeza Rice, Michelle and Barack Obama, Susan Rice, and Colin Powell, just to name a few – who belong to what used to be called the “talented 10th,” (I suspect their percentage is a lot higher now) and whose parents, in the best meritocratic/credentialist tradition, urged them throughout their childhoods to get the best educations available.

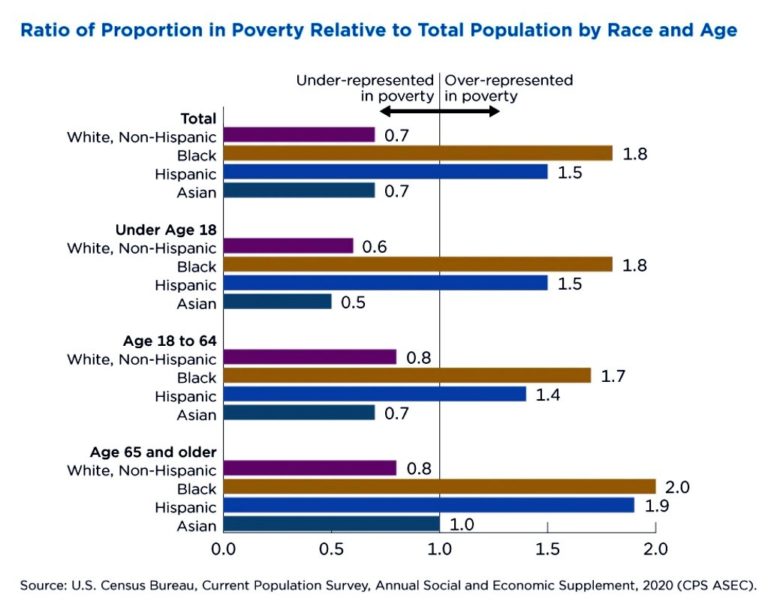

Nevertheless, Black poverty is still out of proportion to the Black population, which represents “13.2% of the total population in the United States, but 23.8% of the poverty population.”

Is this the result of Black economic failure? Definitely. Is Black Economic failure the result of innate racial inferiority? A lot of Whites think so: the Southern Poverty Law Center reports that 49% of Americans today believe that “people of color are more likely to be poor because of a lack of work ethic.”

Sandel’s critique of meritocracy helps us dismiss the insidious presumption that if you haven’t made it economically it is your own fault. Nonetheless, the meritocracy is far less accessible to Blacks and to people of color than to Whites, because Blacks carry the weight of generational disinheritance.

For example, after World War II a white soldier could use the GI Bill to get a college education. A Black soldier could not. The white veteran could go to a bank to get a loan for the mortgage on his first house. In the north as in the south, Blacks have been consistently denied bank loans for housing or to start a business.

Having missed out on generations of real estate equity, many Black people today still can’t afford to make that first significant investment in their own homes. Should they happen to own one, their property is still devalued along racial lines: Just last week, a Black woman asked a white friend to help secure a new mortgage on her house. When the Black woman was taken as the owner the appreciation came in thousands of dollars lower than when her white friend applied.

Blacks are forced by “redlining” – mapping off Black from white housing, a widespread practice in the north as well as the south – to live in segregated areas and send their children to underfunded schools. Black neighborhoods are often “nutritional deserts,” with no grocery stores where fresh meat and produce can be purchased for miles and miles around. This leaves Blacks with a higher proportion of diabetes and heart conditions and with significantly lower life expectancy than other Americans.

Stopped by police for no reason at all – shopping while black, driving while Black, jogging while Black, walking through a white neighborhood while Black – join daily personal microaggressions to undermine Black psyches with anxiety and dread.

J.M. Holmes’ short story “Children of the Good Book, ” describes the life of a Black man, Bull, a huge proponent of hard work although he “worked the darkest part of the night cleaning offices where he couldn’t get hired.”

“You liked to talk about honest work, but what you never understood, Bull, is there ain’t no such thing in a dishonest system….As you sweat in the halls of that last building, scouring the white man’s refuse from his corporate temple, was it on your mind? …..You’re not the first of us that’s lost himself and you damn sure won’t be the last. They’ve been dragging us deeper into the desert for four hundred years.”

The Common Good – Utopian Dream or Practical Possibility?

Clearly, Black Americans have never been fully included in the American commons. As we approach a “majority minority” demographic, with more Black citizens voting and achieving political prominence, the greater the white backlash. I will never forget Civil Rights Hero Jesse Jackson’s tears of joy in Grant Park, Chicago, when Barack Obama strode out to accept his presidential victory; I will never forget the mob of 70,000 “Tea Party” protestors a friend and I encountered rallying on the Washington mall soon after his election, roaring their intent to “Bury Obama”.

Will racial inequality, as Derrick Bell suggests, continue as a permanent economic and social determinant in American culture? There was that terrible event in Charlottesville when their raging faces lit by Tiki Torches, White Supremacists chanted the Nazi slogan “YOU WILL NOT REPLACE US!” as they marched through the night.

There was that wonderful video when Biden’s nomination vote was gathered in from the states, displaying American citizens in the glorious panorama of our diversity.

Carrying through after his election on a promise to build an economy based on diversity rather than exclusion, on distributive and contributive justice for the many rather than on competition-based profit-taking for the few, President Biden has taken to winding up his speeches, gazing out on his widely diverse audiences, with the declaration that “THIS IS AMERICA!”

Sandel argues that focusing on the Gross National Product following an ethic of meritocracy will destroy us, while a transition to an economy based on the good of the whole will save us. Bidenomics, which puts money in the pockets and education within reach of every American citizen, widens the common good to include all Americans.

White Supremacists, who violently attacked the Congress to prevent the certification of Biden’s election, now dominate the Republican Party and are determined to vote down everything he proposes. They have no political policies at all – they did not even bother to present a party platform in their 2020 primary – but are motivated by a fierce dread of racial replacement combined with a fascistic lust for retaining power.

The two slogans – YOU WILL NOT REPLACE US! and THIS IS WHAT AMERICA LOOKS LIKE! – divide our Congress right down the middle. One looks to a democratically achieved, diverse and inclusive future, the other to racial exclusion and voter suppression.

It is left to those of us who believe in a common good achieved through the rule of law to strengthen our political will and defend the common good. Open it up to all people alike, Black Americans and People of Color. At the same time, we need to remain constantly alert to the powerful fascist and racist currents that are threatening to undercut democracy itself.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com contributors are their own, not those of Impakter.com Featured Image: Low Memorial Library on Columbia University’s 2005 Commencement, on 18 May 2005 Photo by © Jorge Royan / http://www.royan.com.ar / CC BY-SA 3.0