Alicia Eggert, is an American interdisciplinary conceptual artist, whose artworks in the form of kinetic, electronic, interactive sculpture and installations focus on the relationship between language, time and image.

Alicia’s artworks have been exhibited at different local and international museums in Beijing, Milan, Sydney, Leuven. Her recent solo exhibitions took place at The MAC in Dallas, T+H Gallery in Boston, Harvard Medical School in Boston, and Artisphere Arlington, VA.

Impakter Magazine had an interview with Alicia Eggert, in which she shared her story, inspiration, challenges and what is behind her installations.

Impakter Magazine: How and when did you discover your passion for art? What is your story?

Alicia Eggert: I was born in New Jersey and raised in a strict Evangelical household, and I always was (and still am) the black sheep of my family. My father was the minister of a Pentecostal Church, which practices speaking in tongues, and my parents were missionaries to South Africa from 1986-1990. We lived in a suburb of Cape Town during those last few years of the Apartheid, and I went to an all-white public school while my father started a multiracial church in the city. We returned to the United States shortly after Nelson Mandela was released from prison, and my father became the head pastor of a church in New Jersey, where I spent the remainder of

my childhood.

I began questioning the Christian faith in high school, and I became an atheist in college, but as an adult, I have realized that my upbringing in a religious and politically active family is seminal to my work as an artist. I have come to believe that art, religion, and science, which are often thought of as opposing, have something really important in common: wonder.

Wonder is both cognitive and spiritual. It’s the curiosity that drives us to learn new things about the world around us, but it’s also the feeling we get when we encounter things that are beyond our understanding.

My art practice is founded on my own sense of wonder, and my goal is to create objects and experiences that inspire a sense of wonder in others.

IM: Your artworks are primarily kinetic, electronic and interactive sculpture and installations, focusing on the relationship between language, image and time. What has triggered you to choose exactly this direction of art?

A.E.: It wasn’t until my senior year in college at Drexel University, where I majored in Interior Design, that I took a sculpture class that introduced me to conceptual art. The fact that art could be based on an idea and not on process or technical skill pretty much blew my mind. I decided at that point (I think I was 21 or 22) that I wanted to be an artist, but it took me several years to work up the courage to give myself that title. Although I was always a creative person, even as a child, I had never thought of myself as an “artist,” and I felt the title was something I had to earn. After college, I worked as a designer at an architectural firm in New York for several years, making art on my spare time, before eventually quitting my job so that I could focus on building a portfolio for graduate school. I eventually went to Alfred University to get an MFA in Sculpture/Dimensional Studies.

Although I consider myself a sculptor, my primary concern is with the fourth dimension, time, because time is synonymous with existence. It serves as a constant reminder of our mortality. So I think the motivation behind most of my work is an existential one. I try to reconcile the linear and finite and nature of human life within a cyclical and seemingly infinite universe. We experience time as a continuous progression from the known past to the unknown future, yet we often struggle to forget the past and predict the future. In my work I attempt to blur the distinction between absence and presence, and to regard the past, present and future as a whole. Much of my inspiration is derived from scientific research – scientific data, theories such as relativity, and current explorations of deep, cosmic time. I’m especially interested in the relationship between time and space.

I consider language my primary sculptural material, and this largely stems from the fact that I am a conceptual artist. It’s probably also tied to my religious upbringing in some way. So much of my childhood was spent studying the Bible, and listening to people give sermons that basically picked different scriptures apart word by word, in order to define them and find meaning in them. When I am trying to understand something like time, I start with the words we use in our everyday language. I deconstruct and then words like “now” and “eternity” conceptually and also physically, the way another sculptor would deconstruct a found object like a chair. Incorporating the element of time into my work, through the use of kinetic mechanisms like motors and sensors, was an obvious step for me because it is exactly what the work is trying to figure out.

“Unless you see signs and wonders,” it says in John 4:48, “you will never believe.” The religious community in which I was raised believes strongly in signs and prophecies, which might be why I am drawn and the forms and strategies associated with commercial signage and advertising. Most signs we encounter in our daily lives don’t necessarily tell us what to believe or why we exist, but rather what to eat and drink, how to spend our money, and where to exit the highway. My artwork co-opts these familiar forms and employs them to encourage thoughtful introspection and reflection, to ask unanswerable questions, and to highlight the wonders that can still be found in our everyday realities.

IM: What is an installation that you are very proud of?

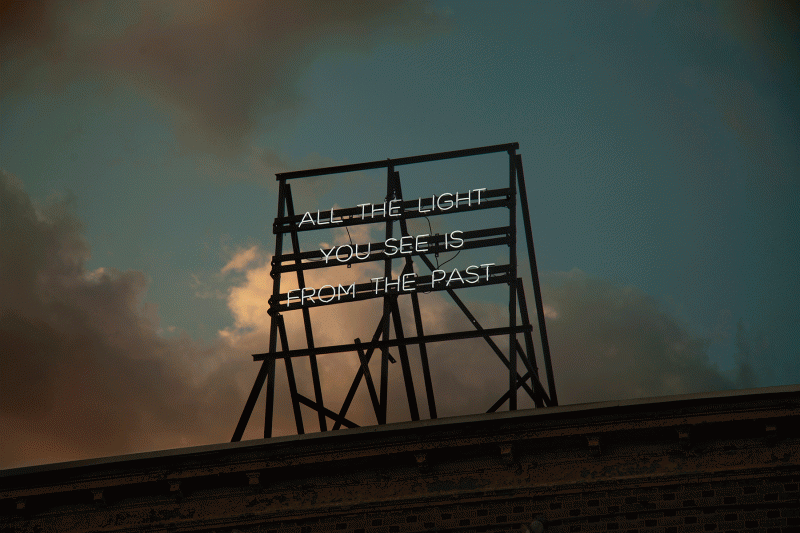

A.E.: One of my most recent ones – “All the Light You See” (2017)

I was invited by a curator in Philadelphia named Ryan Strand Greenberg to create custom neon signs for an abandoned building in a gentrifying neighborhood Philadelphia. The building used to be a beer distributor, and it had recently been bought by a developer who planned to demolish it in order to build apartments. The building had a pre-existing steel sign structure on its rooftop, onto which I could temporarily mount some neon letters. The flashing neon sign I put up cycles through the statements “All the light you see is from the past” and “All you see is past” before turning off completely.

It speaks to the fact that light takes time to travel, so by the time it reaches your eyes, everything you are seeing is technically already in the past. Light from the moon left its surface 1.5 seconds ago; sunlight travels for 8 minutes and 19 seconds before it touches your skin. The farther out into space we look, the farther back in time we can see. This sign, and the building it sits upon, is an image of what was. It will be demolished sometime this spring. I have been given permission from the developers to leave the neon installed during that process so that it, too, will be destroyed. I intend to film the sign’s demise, and to document and collect its remains.

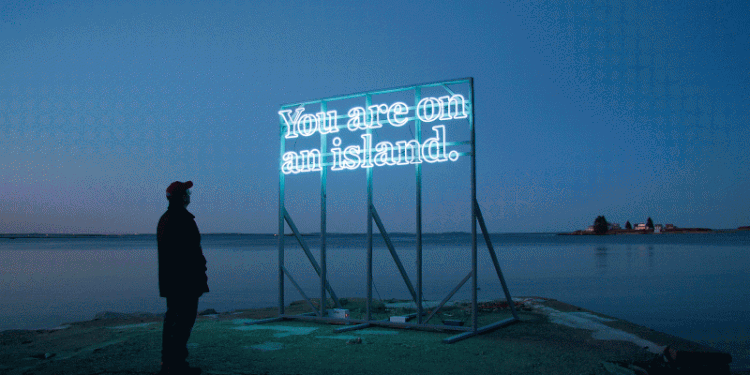

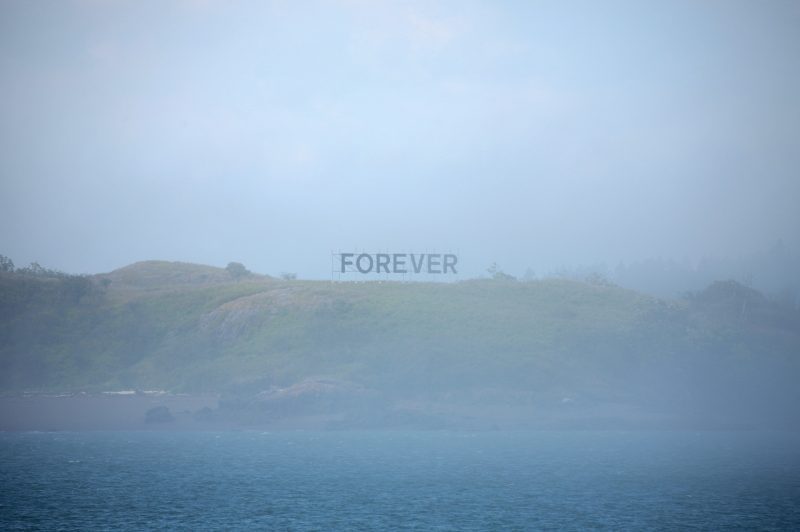

IM: Your conceptual art installation “You are on (an) island” triggered a vivid discussion. Installation brings 2 messages, it might includes several different interpretations. What is your interpretation? What impact did you aim to bring to the person, who sees this installation?

A.E.:“You are (on) an island” was originally created in 2011 for The Sacred and Profane art festival on Peaks Island, Maine. The flashing of the word “on” was meant to transform an initially obvious and literal statement into a reflective and philosophical inquiry. The sign suggests that you as an individual are, like an island, isolated from other human beings in both your body and your mind. However, the word “on,” when it appears, reminds you of your place in the world. By constantly flipping between these two statements, You are (on) an island prods you to think both inside and outside of yourself, inviting you to marvel at the world you inhabit and the role you play in it.

Since its initial debut on an island in Maine, the sculpture has been shown in lots of different places around the world: the Malta Arts Festival in Birgu, Malta, Sculpture By the Sea in Sydney, Australia, and the DUMBO Arts Festival in Brooklyn, NY. It has also been presented as a mobile sign, mounted on the back of a flatbed truck and powered by a generator. It was taken on a “guerrilla sculpture tour” of the UK in early 2013, a project which was sponsored by Neon Workshops in Wakefield and funded by a Kickstarter campaign, and which culminated in the release of a limited edition publication. It later toured around Arlington, Virginia and Washington DC in conjunction with my 2013 solo exhibition at Artisphere. And in these locations, the kind of “island” people find themselves on is not necessarily the geographical kind. More likely, people (especially right now in the US) are on political or ideological islands.

IM: What challenges have you faced during your creative process?

A.E.: Installation process can be stressful, especially when I am working with a fragile material like glass that might break. It’s also sometimes stressful that, because I am a conceptual artist, I find myself always working outside of my technical comfort zones, having to learn to do new things in order to bring new ideas to life. I am a jack of all trades but master of none, because the materials and processes I work with from project to project vary tremendously. But the older I get, the more I become comfortable admitting, even to my students, that there is so much I don’t know, so much I have yet to learn, especially these days, with the constant development of new digital fabrication tools and techniques. The umbrella of sculpture is so big, and the field encompasses so much, that it’s impossible to be an expert in everything.

IM: In another interview you said that your most successful projects “are those that were made in collaboration,”. Can you share with Impakter readers with your collaboration tip?

A.E.:I think it’s because I am a conceptual artist that I enjoy making work in conversation. I’ve always said that I believe ideas only get better when they are bounced around a bit, like a good pair of jeans. I enjoy working with people who have a technical expertise that I don’t possess, like Alex Reben’s engineering background and the way our individual strengths and research interests were able to combine in such a beautiful way to create Pulse Machine. But even when I am not collaborating with another artist, I enjoy bouncing ideas off of my friends and student assistants, and asking people for their opinions. I also believe that the art world has hung on to the idea of the solitary artist genius for far too long. Many successful artists have assistants and fabricators these days, but most artists don’t give those people credit for their work. It’s my hope to change that culture, and create a way to give credit to all the people involved on a project, the way musicians list all the artists who wrote and played the songs on their album, and the way the film industry has a long credit roll at the end of every movie. I’m not sure what the equivalent would be in the visual art world, but at the very least we should list all this information on the wall labels in exhibitions. Whatever the solution, it’s time that we figure it out and stop pretending that only one person is responsible for creating something that was most likely the product of so many peoples’ efforts.

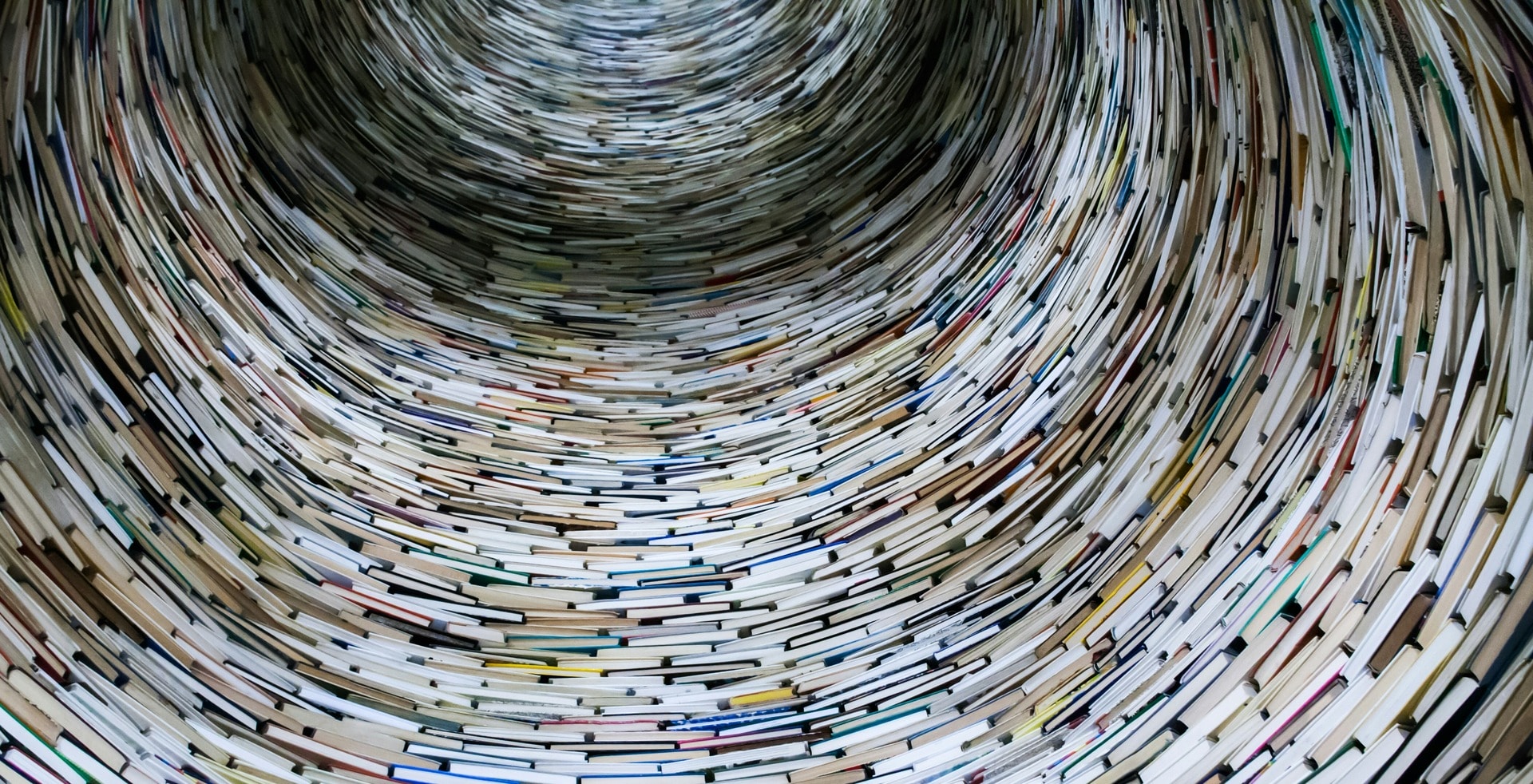

Where do you find inspiration?

A.E.:I find inspiration all around me, especially in signs that I see on the highway or driving through small towns. I find it in scientific theories like relativity and wave-particle duality. I find it in science fiction novels by Octavia Butler and Philip K. Dick, and in nonfiction books about time and language, like The Information or Time Travel: A History by James Gleick, or The Clock of the Long Now by Stewart Brand, and all the writings by Georges Perec. And I am always inspired by the work of other artists.

What is your philosophy behind your installations?

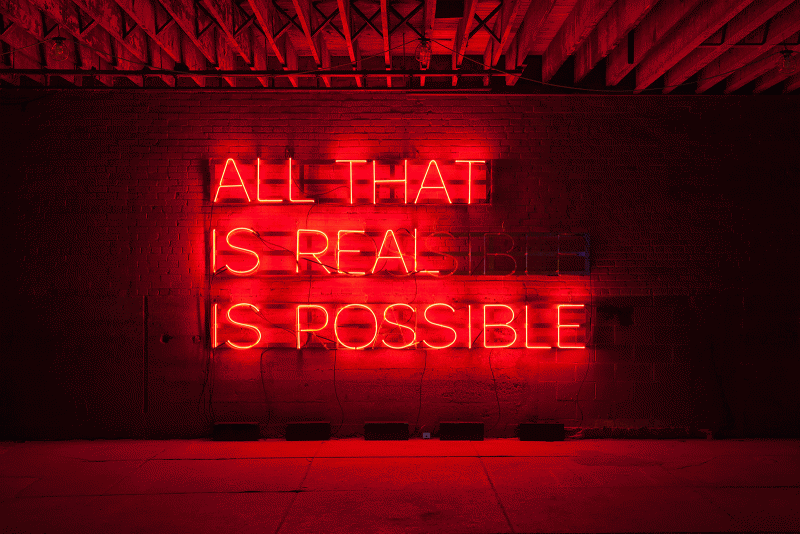

A.E.:The future of our planet and our species is now uncertain in a way that it never was before. Our ecological clock is ticking. I am inspired by a quote from Immanuel Kant’s Logic of Pure Reason, that if all that is real is possible, then all that is possible is also real (I made a neon sign inspired by this for the True/False Film Festival). This idea is kind of like Schrodinger’s multiverse hypothesis – that an infinite number of universes and each universe contains an alternate reality, the idea being that everything that was ever possible, anything that ever could have happened actually did, in a different, parallel universe. So, what do these other realities look like, and if that reality is what we want to live in, how can we make this reality look more like that reality? My hope is to generate an open dialogue about what we value as individuals and as a society, and to encourage people to focus not just on what is real, what is possible – a personal dream or goal, or the hope for a better and more peaceful world. If all the light we see is from the past, then the hope for a brighter and more peaceful future lies in our ability to imagine it first, and then work towards making it so.

What are your plans for the next year? Are you planning to experiment with new materials?

A.E.:I plan to film the demolition of my “All the Light You See” sculpture in Philadelphia, and present that video along with a recreation of the sign as an infinity mirror for a solo exhibition at Galeria Fernando Santos in Portugal in the summer of 2019. I am also working on a temporary public art project for the City of Arlington in Virginia titled “You Are Magic.” It will involve a making giant inflatable sculpture that will be activated by the action of people holding hands to complete an electrical circuit. It will travel around Arlington for week in May of 2018. I am also working on a large-scale flashing neon sign for the City of Dallas that says NOWHERE (and it will flash on and off to reveal the words NO, NOW, WHERE, HERE). And last but not least, I am working with a computer programmer friend named Charlie Hoey to create a holographic sculpture of the moon that waxes and wanes in real time. A large percentage of each of those projects involves learning how to do things I’ve never done before… and that’s a little scary, but that’s also what makes it fun.