Editor’s Note: A special acknowledgment goes to Jane Madgwick, CEO of Wetlands International , one of the authors of the report referenced below: Water Shocks: Wetlands and Human Migration in the Sahel.

Agreed upon in a flurry of optimism in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) ambitiously promise a fair and just world for people and the environment. We were one of the organisations feeling optimistic as the SDGs were agreed upon – wetlands are mentioned in two of the targets and they are relevant to at least eight of the 17 goals. We were pleased to see this strong link between wetlands and the SDGs.

Wetlands occur where water meets land. This includes marshes, peatlands, rivers, lakes, deltas, floodplains and flooded forests. Just as wetlands link and regulate water throughout the landscape, from the mountains to the sea, they are also an indispensable link within the SDGs. They provide a wide range of benefits to society, including clean water, food and fish, unique nature, improved local economies, and coastline protection. They regulate water flows to prevent desertification, droughts and floods, and remain Earth’s greatest natural carbon stores. Clearly, safeguarding and restoring wetlands will go a long way in achieving the SDGs.

Just as wetlands link and regulate water throughout the landscape, from the mountains to the sea, they are also an indispensable link within the SDGs.

Optimism, however, can be hard to sustain. The recently released Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017 shows that some progress has been made towards the 2030 Agenda: the global rate of extreme poverty has fallen, undernourishment has declined, and the proportion of urban populations living in slums has fallen. But overall the report shows progress has been too slow to achieve the SDGs by 2030. For the millions living in poverty and precarious situations in Africa’s Sahel region, the report’s statistics offer little hope of an immediate improvement in their situation and many are taking matters into their own hands. In the last two years, there has been an exodus of people from the Sahel crossing the Mediterranean in overcrowded and unseaworthy boats.

Photo Credit: Sea Watch Org/Judith Büthe

There are many factors behind this migration but we believe that a link can be made between poor water management, wetland health, disrupted livelihoods and involuntary human migration. This year in May we published the report Water Shocks: Wetlands and Human Migration in the Sahel in order to further establish the links in this chain.

Sahelian Wetlands are the Beating Heart of the Region

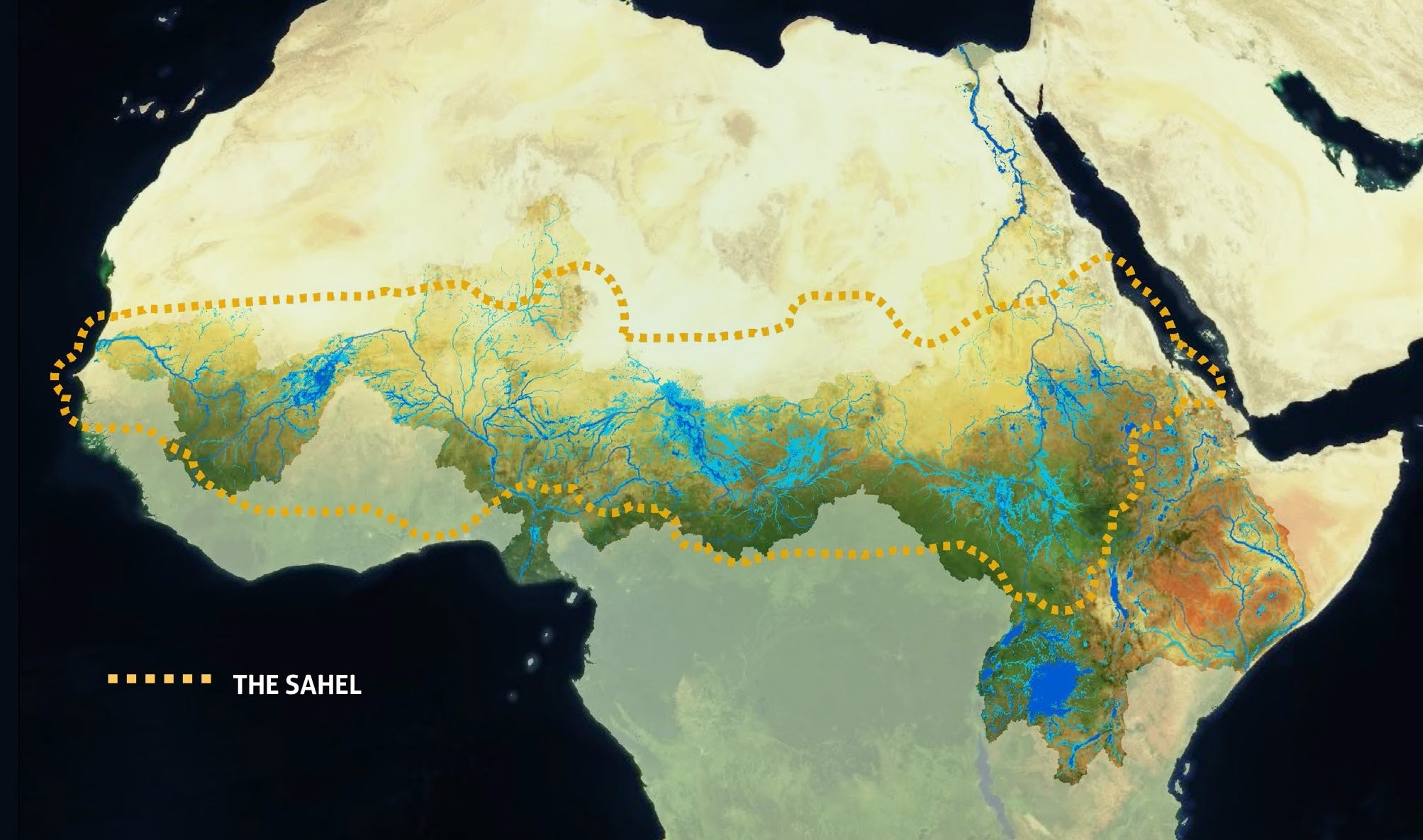

The Sahel is a semi-arid region extending across Africa from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea. Dotted across this landscape are green oases – wetlands that expand during the wet season and shrink during the dry season. They are a lifeline for the region’s poor, who depend on them for food, fuel and water.

However, in recent decades many of the Sahel’s rivers have been dammed to store water and control water flows for hydroelectricity and irrigation. These dams have benefits for urban electricity users and some farmers, but they have had a profound impact on those who depend on wetlands for their livelihoods. As the report states, “In very low rainfall years, when the wetlands all but disappear, the result is a humanitarian disaster.”

Photo Credit: Wetlands International

The Root Causes of Migration

Migration from Africa to Europe has increased and European governments are starting to pay attention. In 2015, the European Union promised €1.8 billion to tackle the root causes of migration. But what are those root causes?

Growing populations, development projects, and ethnic tensions compel those who can to leave. At the same time, many are drawn to the cities and Europe by job opportunities, the allure of new lifestyles, and family and friends who have already migrated. But there is strong anecdotal evidence that the environment also plays a role in migration.

Related Article: “SMALL-SCALE FISHERIES: SUSTAINABLE COASTAL DEVELOPMENT’S URGENT (AND UNKNOWN) FRONTIER“

We explored this in the Water Shocks report through four case studies: the Senegal River, the Niger Delta, Lake Chad and the Lorian Swamp. In all four cases the story is the same. Diverting water impacts those living downstream who depend on wetlands for their livelihoods. Without water to grow crops and pastures for feeding cattle, farmers and herders simply cannot live off the wetlands anymore.

Photo Credit: Wetlands International

The Senegal River

In 2016, journalist Fred Pearce took a journey along the valley of the Senegal River and spoke to people living in villages there. Since the 1970s OMVS (Organisation for the Development of the Senegal River) has built two dams on the Senegal River and its delta. The Manantali dam in Mali holds back the floods. But it is precisely this flood pulse that farmers, herders and fishers depend on.

Pearce interviewed Seydou Ibrahima Ly, a teacher in the riverside village of Donaye Taredji, who starkly stated the problem his village is facing, “Compared to the past, there aren’t many fish. Our grandparents did a lot of fishing but we don’t… In the past, the rivers had a flood that watered wetlands where fish grew. Now there is no flood because of the dam.” Around 100 people have already left Ly’s village and in other villages almost everyone has left.

Since the drought of the 1970s, many Senegalese moved to cities. Recently, however, more and more are fleeing, going across the Sahara to Libya and then by boat to Europe.

Photo Credit: Eddie Wymenga

Increasing Conflict in the Region

We also see a link between environmental degradation and increased social breakdown and conflict. This is particularly evident around Lake Chad, where Boko Haram has been killing and abducting people, displacing more than 2.3 million who are fleeing the violence. Many have joined those migrating to Europe.

Poverty, civil conflict and the spread of terror groups have been blamed. But the fact remains that Lake Chad has lost 95 percent of its surface area since the early 1970s. Rivers feeding the lake are being abstracted for irrigation. Farmers, fishers and herders are competing for limited resources, causing tensions, conflict and migration to ensue.

Photo Credit: Lake Chad 1972/2007 UNEP

Photo Credit: Lake Chad 1972/2007 UNEP

Opportunities for Change

Many of the SDGs, if implemented with proper wetland management in mind, could contribute to reversing this trend of increasing social conflict, poverty and migration in the Sahel. Goal 13, Climate Action, will play a vital role. We argue in Water Shocks that climate change and drought are not the primary reasons for diminishing wetlands. However, if governments respond to rising temperatures and increased uncertainty over rainfall by building more large-scale dams and irrigation schemes, the situation in the Sahel will worsen. Instead, governments should invest in the natural systems, such as wetlands, that buffer climate extremes.

Goal 2, Zero Hunger, aims to end hunger. The Sahel’s wetlands are a vital source of food in the region. For instance, the Inner Niger Delta in Mali provides pastures for a third of the country’s cattle and sustains 2 million people, 14 percent of the population. Its fish are exported across West Africa. Governments of Sahelian countries should be working to protect these wetlands and avoid food production strategies that will damage them. After all, increased food production does not necessarily equate to food security: More for some can mean less for others.

Photo Credit: UNHCR/F. Noy

Goal 6, Clean Water and Sanitation, includes a target specifically mentioning wetlands: By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including… wetlands. But conventional policies to improve water security have long relied on dams and irrigation schemes. Meeting targets for drinking water access and sanitation have also undermined the water security of the most vulnerable.

It is promising that the SDGs acknowledge the role of wetlands, but including wetlands in development plans requires that governments and responsible departments have the capacity, knowledge and willingness to do so. What’s more, the benefits of wetlands often remain invisible. That’s why we are calling on civil society, businesses and governments to act now for wetlands.

Authored By: Naomi Racz

Naomi Racz has an MA in Nature Writing and has been a Communications Officer at Wetlands International since 2015. Through web, social media, newsletters, video and infographics she tries to answer the questions: what are wetlands and why do they matter? Naomi has been working on wetlands and the SDGs since they were finalised in 2015 and is currently helping to organise a stakeholder meeting in India in 2018 on investing in wetlands for Agenda 2030.

Naomi Racz has an MA in Nature Writing and has been a Communications Officer at Wetlands International since 2015. Through web, social media, newsletters, video and infographics she tries to answer the questions: what are wetlands and why do they matter? Naomi has been working on wetlands and the SDGs since they were finalised in 2015 and is currently helping to organise a stakeholder meeting in India in 2018 on investing in wetlands for Agenda 2030.