In a televised interview in 2020, anti-mafia writer Roberto Saviano criticised then-Deputy Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s policy of not rescuing migrants in the Mediterranean. In a move that has press rights activists from around the world concerned, Giorgia Meloni, now Italy’s Prime Minister, is suing Saviano for criminal defamation.

The freedom of the Italian press is at stake in this case, in which a private citizen and journalist is being threatened with incarceration due to comments aimed at government officials and their policies.

Intimidating and threatening journalists is a common practice in Italy and one that is threatening the very existence of a free and independent press in the country. Italy ranked 58th in the 2022 World Press Freedom Index published by Reporters Without Borders, the lowest level in western Europe.

Who is Roberto Saviano?

Roberto Saviano’s 2006 book “Gomorrah: A Personal Journey into the Violent International Empire of Naples’ Organized Crime System” named high-level members of the Italian organised crime group Camorra.

The book was commercially successful and led to the hit TV series Gomorrah.

However, many of the mafiosos who were identified by Saviano faced charges and were convicted as a result of the book, which led to Saviano receiving death threats and other forms of intimidation.

Due to these threats, then-Minister of the Interior, Giuliano Amato assigned police protection to Saviano from Oct. 13 2006, and Saviano has lived under protection ever since.

He continues to be an outspoken anti-mafia journalist, writer, and human rights activist, although he has admitted: “I am aware that I am not brave when I say, if I went back in time, I would act more cautiously.”

To many Italians, Saviano is seen as a modern hero and champion of justice for the Italian communities that have lived under the informal tyranny of these criminal organisations for decades.

In December 2020, Saviano appeared on the political TV chat show “Piazzapulita” and was asked to comment on the recent death of a six-month-old baby from Guinea during a shipwreck in the Mediterranean a month earlier.

Saviano gave the following statement in response:

“All I can say is: they’re bastards – Meloni, Salvini… How is it possible, over such desperation? They have a policy, legitimately, which opposes that of reception [of migrants] – but surely not in the case of an emergency in mid-sea.”

In response to this public outburst, Meloni issued a writ for criminal defamation in November 2021, when she was leader of the opposition. Now as the prime minister, she continues to stand by the case and her claims.

Migrant Rescue: A Divisive Issue in Italian Politics

The Mediterranean is the world’s deadliest border and has witnessed 1,200 deaths in 2022 and a staggering 25,000 since 2014.

Italy’s position as a peninsula stretching out into the middle of the Mediterranean means that it has been the recipient of the greatest portion of migrants attempting to traverse the sea since 2014. To say that immigration has become a divisive topic within Italy and its political landscape would be an understatement.

It wasn’t always so. In the early 2000s, Domenico Lucano, the Mayor of Riace, a small town in Southern Italy, developed a remarkable model to welcome refugees which, by giving them housing and work in the local economy, would help integrate them into Italian society. Right-wing parties in Italy vocally and endlessly criticised Mayor Lucano’s migrant projects.

Not only did Riace’s pro-migrant policies cease after the Right rose to power in 2020, spearheaded by the right-wing populist political party Lega Nord led by Salvini, but on October 2, 2021, Lucano himself was convicted of fraud, embezzlement, criminal association, and abuse of office by the court in Calabria.

He was given a jail sentence of more than 13 years. The conviction caused public outcry and was called “the gravest repressive attack on the culture and the practice of solidarity in our country.”

In the Italian 2022 general election, Giorgia Meloni ran on a platform that included, among other traditionally right-wing positions, a total end to immigration into Italy. She suggested that this be done by means of a naval blockade along the coast of North Africa.

Salvini, now the Deputy Prime Minister, has also centred his political career on anti-immigration sentiment. In one comment from a past interview, Salvini went so far as to explicitly relate the migrant crisis to his own concern for the future racial purity of Italy, saying:

“My objective is to give economic serenity to Italians to encourage them to have children. I refuse to think of substituting 10 million Italians with 10 million migrants.”

In July 2019, Meloni discussed the issue of migrant rescue on the same TV channel, La7, that would later host the interview with Saviano. She stated that the law of the sea directed the rescue of drowning people only in “occasional” circumstances when the ships in trouble were engaged in “inoffensive passage, as distinct from passage prejudicial to the peace and security of nations”. She continued to explain that ships engaged in “the illegal transport of human beings” into Italian waters “are not inoffensive passage” and, therefore, rescue was not a legal requirement.

Currently, in her new role as prime minister, Meloni is trying to enact a ban on receiving migrant ships in Italy.

Related Articles: Killing the Journalist Won’t Kill the Story | Illegal Pushbacks in Greece Are Costing Refugees Their Lives | Why Populism is Dangerous: The False Migrant Crisis and the Real One

The European Commission, after being asked if such a ban is legal under EU law, stated that it had “no competence to decide which boats can or cannot enter a country’s territorial waters.”

Italy’s refusal to accept migrant ships caused friction with France last week, as French President Macron reluctantly accepted boats that had been turned away from docking in Sicily and harshly criticised the Italian government’s choice not to allow the boat safe harbour.

1/2 🔴Breaking: At around 11:30 am, the #Humanity1 was asked to leave the port of #Catania with 35 survivors on board. The captain has refused this order. Maritime law obliges him to bring all those rescued from distress at sea to a place of safety. pic.twitter.com/SiyjCOjtR3

— SOS Humanity (international) (@soshumanity_en) November 6, 2022

Meloni is not alone in her position. Many EU member countries, including the more “illiberal” governments of Hungary and Poland, have refused to accept migrants. A continuing lack of solidarity among EU members and a widespread reluctance to modify the Dublin Regulation is preventing the EU from making progress towards a solution that might satisfy, or at least pacify, all of its member nations.

How Free is the Italian Press?

As mentioned above, Reporters Without Borders found that in 2022, Italy ranked the lowest of any nation in Western Europe for freedom of the press. Given that an independent press is fundamental to a fully functional democracy, this finding raises serious concerns about the current status of both freedom and democracy in Italy.

Saviano continues to defend his remarks and has said regarding the charge and upcoming trial:

“From Meloni and Salvini came ferocious and inhuman anti-migrant propaganda. Meloni speaks of these NGO ships as pirates; she’s said they should be sunk, their crew arrested… In the light of this, and the libel charge, do you really think mine were such offensive words? Defining [a category of people] as delinquents, rapists and drug pushers? And now a ‘residual burden’? That’s what I call offensive…to ruin people’s lives with propaganda.”

In Italy, 9,479 defamation proceedings were brought against journalists in 2017 alone according to data from the Italian National Statistics Institute (ISTAT).

Although libel would constitute a civil law case in many countries, in Italy, defamation can be a criminal charge that has a maximum sentence of up to three years. The criminal code also provides for higher penalties to be applied if a political, administrative or judicial body has been defamed.

Observers say that these defamation trials are demonstrative of a culture in Italy in which public figures, typically politicians, are able to erode the existence of a free and independent press by intimidating reporters with repeated lawsuits.

PEN International has written an open letter to Meloni expressing support for Saviano and concerns for the future of the Italian press:

“As the Prime Minister of Italy, pursuing your case against him would send a chilling message to all journalists and writers in the country, who may no longer dare to speak out for fear of reprisals.”

Grazie al @pen_int per il suo supporto. Per il Pen, uno scrittore portato a processo da ben tre ministri di questo governo (Meloni, Salvini, Sangiuliano) è una minaccia alla libertà di espressione nel nostro Paese. Intimidirne uno per intimidirne cento.https://t.co/pg9i6oZvnI

— Roberto Saviano (@robertosaviano) November 8, 2022

Italy’s Constitutional Court has actually ruled that jail time for such cases is unconstitutional and should only be resorted to in cases of “exceptional severity”. In 2020 and 2021, they urged the Italian parliament to rewrite the law.

Meloni’s lawsuit against Saviano is the second time that the anti-mafia writer has been charged with defamation by an Italian political figure.

In 2019, Matteo Salvini, then-interior minister and current right-hand man to Meloni, charged Saviano for criminal libel. Saviano had called Salvini “Il Ministro della Mala Vita” or “the minister of the criminal underworld”, a phrase used by anti-fascist intellectual Gaetano Salvemini in 1910 against the the prime minister of the time.

By chance, Saviano named both Salvini and Meloni in his comment to Piazzapulita, for which he is being taken to court by Meloni on Tuesday. However, Salvini’s charge of defamation is separate and unrelated to the Piazzapulita interview; the trial for that case is set for February of 2023.

How Does the Future of Journalism Look in Italy?

Free press activists and international human rights organisations alike have expressed concern at this latest move from Meloni.

Saviano himself noted:

“It will be even more difficult (for journalists) to report on what is happening and express an opinion if the prospect is having to defend one’s freedom of expression in court and seeing your words put on trial when they criticise power and its inhuman policies.”

The international spotlight on the upcoming trial has called renewed attention from European institutions and intellectuals on the situation of the press in Italy, with most calling for the end of the use of criminal law for cases of defamation.

Mexican-American Jennifer Clement, president of PEN International, said:

“Roberto Saviano has repeatedly risked his life to expose the truth about Italy’s criminal networks… and today he faces up to three years behind bars. Italy should end the use of criminal law in regard to defamation.”

Roberto Saviano sacrificed his freedom and safety to expose criminals who terrorise and threaten Italian communities. His actions are emblematic of how important a free press is to the welfare of a nation’s citizens.

By pressing criminal charges for these statements, both Meloni and Salvini continue to contribute to the erosion of free press in Italy and show that their concern for the citizens of Italy is almost as low as for those who seek to take refuge there.

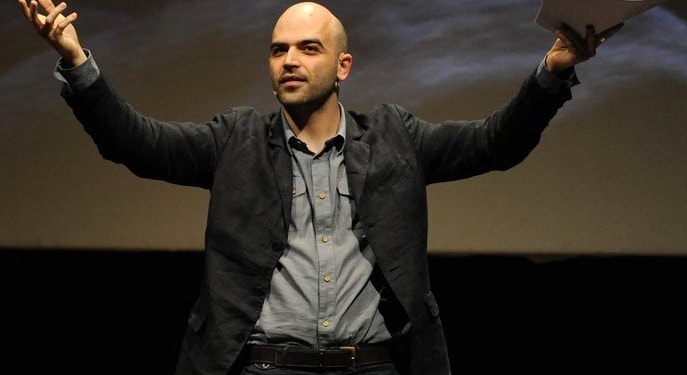

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: A photo from 2011 of Roberto Saviano, the author and journalist being sued by Meloni. Featured Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.