Recycling has been a commonly practiced form of waste disposal for decades, an eco-friendly option for getting rid of our unwanted goods or packaging, and a way to make new products without having to source raw materials.

We are taught to believe that everything we put out into a recycling bin will be turned into something new, and avoid the ever increasing colossal landfill piles that our non-recyclable waste is dumped on and sits for eternity.

But is our common form of household waste disposal really as green as we think it is?

Where does recycling waste go?

According to Statista, the USA is the world’s top producer of plastic waste, the UK is second and South Korea is third.

Let’s take a look at what percentage of this waste is recycled, what percentage is supposedly recycled, and how much of it is ending up in landfill.

The British Plastics Federation (BPF) estimates that 46% of the UK’s plastic waste is incinerated, 19% is exported to other countries and 17% goes to landfill.

However, according to the governments reports, 44.2% of the UK’s plastic packaging waste was recycled in 2021.

Furthermore, Greenpeace have estimated that over 50% of all UK plastic waste is sent to countries such as Turkey and Malaysia, exceeding the 19% estimation from BPF.

Whether it’s 19% or 50%, exporting waste to third countries is clearly a cop-out, and the reason invoked for doing it is that the UK does not have the capacity to hold the amount of waste it is producing.

Moreover there are a huge amount of different estimates floating around, which strongly suggests that the facts may be purposefully being covered up; and in any case, it may be difficult to get to the bottom of it without carrying out an independent evaluation by some serious research entity and making the findings available on a credible peer-reviewed publishing platform such as IOPP.

The USA, as reported by Statista, are the largest producers of plastic waste per capita, and along with the UK and EU countries, have been previously known to send a huge amount of that to China.

However, in 2018, China imposed a ban on these imports, as large quantities of what was being sent to them to be recycled was dirty and contaminated, and had to go to landfill sites.

China had been importing waste from different countries since the 1980’s to use as a replacement for raw materials that were in short supply.

This 2018 ban from China is one of the reasons for the shift of plastic waste from the UK ending up in countries such as Turkey and Malaysia.

The USA is asking China to lift its ban, and the EU is looking to impose a tax on plastics to discourage people from using them. This is due to the fact there are no longer so many options to get rid of the waste.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, an average of 32.1% of all waste produced in the USA was recycled.

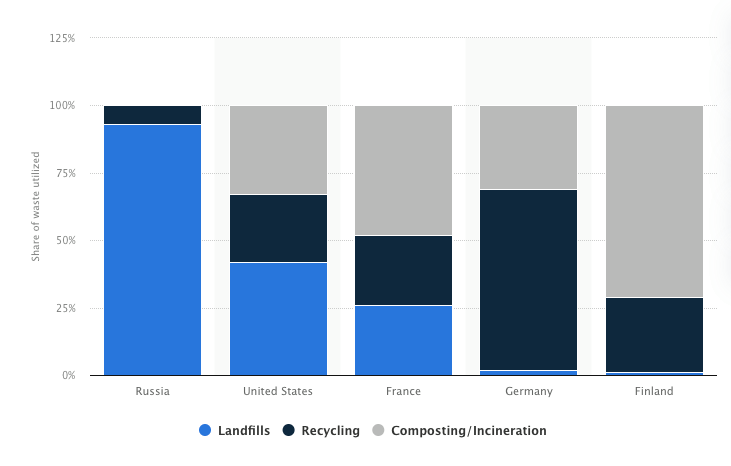

How is recycling practiced differently across the planet?

Germany is considered the country with the highest recycling rate in the world, recycling 66.1% of its waste.

Though it must not be forgotten that Germany also came in 4th place on the Statista data above, showing countries that produce the most overall plastic waste in the world.

We must not mistake the correct disposal of waste as a form of compensation for overconsumption in the first place.

On the other hand, the graph below shows that African countries such as Chad and Sudan, produce very little plastic waste, but because they do not have the facilities to recycle it all, they are not considered “game changers” like Germany in the recycling economy.

What is evident is that countries with fast-moving, strong economies such as Germany, are producing the most waste in the first place, but are congratulated for what they do with it.

Whereas countries in economic difficulty, that do not have the luxury of consumption, are not seen as environmentally beneficial.

Which of the three R’s are most effective? Reducing, reusing, or recycling?

The consumer culture of today has led us to believe that so long as we dispose of our waste correctly, organizing it into the correct colour coded bins, washing out bottles before trashing them, that there is no guilt to be felt about consuming these products in the first place.

We are taught that our responsibility lies in the correct disposal of products, not the consumption of them.

We forget about the energy used to create things, so long as we recycle these things afterwards, not to mention the energy involved in some recycling methods, such as the melting of plastic and glass to make new products out of the material.

Flore Berlingen, director of environmental NGO Zero Waste France tells Politico “The message about recycling is so positive that it becomes an incentive to consider that recyclable waste is not really waste”(bolding added).

Professors at Boston University, Monic Sun and Remi Trudel, looked at how people reacted to recycling awareness campaigns, and found that “The positive emotions associated with recycling, can overpower the negative emotions associated with wasting”.

This shows that the guilt of consumption and disposal are instantly removed as soon as that empty bottle is placed in the recycling bin, out of sight out of mind.

Of course, the energy used to recycle old things and turn them into new, is less than if all products were made from raw materials.

Related Articles: Plastic Recycling: Ditch it or Improve it? | Green Earth Creations: Recycling Waste in Namibia and Supporting Country’s Economic Development | Exxon Doubles Down on ‘Advanced Recycling’ Claims That Yield few Results

However, simply reusing things avoids the entire process of recycling, there is no need for waste collecting, zero energy used for the melting of material, and less new products created because the old ones are being reused time after time again.

So is the traditional form of recycling by melting things down really the best we can do?

An example being, a comparison of the glass bottle disposal system in the UK and Germany.

In the UK, glass bottles are disposed of in recycling bins, taken to recycling centres and melted down to be turned into something else.

Almost every glass bottle that is bought from a shop, no matter what it contains, is a new bottle; it may be made from recycled materials, i.e. old bottles that have been melted down to create a new one, but the bottle itself is a new product.

However in Germany (and a multitude of other countries around the world too), you bring any glass bottles you have used back to the shop, and the shop will pay you (around 20 cents, depending on the bottle) for every item that is returned.

The bottles are then washed, and refilled. Keeping their original structure, and not using up any energy to be made into a new, different shaped bottle.

The concepts of reducing consumption and creating less brand new products by reusing things are ideas that go hand in hand, both methods support each other.

What future for recycling?

On the other hand, recycling can be seen as a separate practice. It can be beneficial for the creation of brand new products, but we must keep in sight the fact that it still encourages consumption and has a higher environmental impact than reducing plastic consumption in the first place, or reusing what has already been created.

Consider the most advanced and sophisticated approaches to recycling as was presented in a recent article published by IOPscience in 2021, “Analysing the Sustainability of Cascade Recycling in Plastic Manufacturing” by Karl Tanti, Arif Rochman and Paul Refalo. Let us note that the authors are affiliated to the Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Malta – in short, they are engineers.

In this study, using as an example a plastic cosmetic packaging company, they endeavored to show that a “three-cascade recycling approach” – referring to a recycling process where materials are reprocessed and reused in a series of three cycles – would help “further sustainability”. After assessing the three reprocessing cycles from product quality, environmental, financial and social points of view, they concluded that this approach did not negatively affect the quality of the produced parts and resulted in significant cost and carbon footprint reductions when compared to a no-recycling scenario.

That sounds very positive until one realises what their basis for comparison is: a no-recycling scenario. But that is surely not the only or the best comparison. As we have seen above, re-use, if correctly organised, is always a possibility. And packaging using non-plastics such as plant-based materials.

There is a glowing future for plant-based packaging materials, made from renewable biomass sources such as corn, sugarcane, wheat, and other crops. One type of plant-based plastic is polylactic acid (PLA), which is made from corn starch, tapioca roots, or sugarcane and can be used for plastic films, bottles, food containers, and other packaging applications.

Many companies are now exploring the use of plant-based materials for their packaging needs. For example, Tetra Pak was the first company in the food and beverage industry to make 100% plant-based milk carton packaging. The carton is made of plant-based polymers, fully traceable to its sugarcane origin. Coca-Cola has also made a 100% plant-based polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic bottle produced from natural sugars found in plants.

Indeed, plant-based plastic bottles could become “the new normal”. This said, in light of the hype and strong role given to recycling in the so-called new “green economy” – a role that nobody can deny, as a recycling scenario is of course better than a no-recycling scenario – one may well wonder whether the launching of real, fully sustainable alternatives to plastic packaging can ever occur that easily, or even become anytime soon the new normal.

We need to remember that recycling is certainly part of the solution, but it’s never going to be, nor can it be the whole solution. There will always be space for alternatives and they should be welcomed.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by the authors are their own, not those of Impakter.com — In the Featured Photo: Old Glass Bottles Featured Photo Credit: Oleksandr Pidvalnyi.