Insects are affected by climate change. In many ways. Some increase in numbers, others migrate or learn new ways to adapt, but most worryingly, many disappear. An insects biomass collapse could lead to an ecological armageddon. This is but one aspect of the start of the Earth’s sixth mass extinction, with huge losses already observed in large animals. Here is a look at what we know so far about insects, as explained in an article on our sister publication, Impakter Italia, authored by Eduardo Lubrano.

Grasshoppers spotted here, locusts over there. Flies and mosquitoes, insects flying in from the South in above-average quantities. Animals that invade cities. What is happening? Should we get weapons and kill them all? Contact pest control bellevue to know how to proceed.

One study conducted in the United Kingdom on data from the last 50 years, has found, for example, that insects have “no place to hide” due to climate change. Bugs cannot regulate their internal heat. Forests and woods, whose shade should have protected species from heating, are influenced by climate change just like the more open grasslands.

The research examined the recordings of the first spring flights of butterflies, moths and aphids and the first layings of bird eggs between 1965 and 2012. As average temperatures increased, aphids are now emerging a month earlier and birds are laying eggs a week before. English scientists say this could mean that animals are going “out of sync” with their prey, which has potentially very serious consequences for ecosystems.

Biomass Collapse

Researchers are increasingly concerned about the drastic decreases in insect populations, which are the basis of a great part of nature. Such relapses could lead to what the WWF’s 2018 Living Planet Report calls a “catastrophic collapse of natural ecosystems”.

Recent data in Europe is deeply worrying. There has been rising evidence of the widespread loss of pollinating insects in Britain in recent decades.

In the video: Climate Change and Bees, a key species for agriculture, threatened with extinction.

Other studies, carried out in Germany and Puerto Rico, have shown that the numbers have been falling over the last 25-35 years. For example, researchers in Germany, over 27 years of study, found that in 63 nature preserves there was an estimated seasonal decline of 76%, and a mid-summer decline of 82% in flying insect biomass. Yet another research has shown that in the Netherlands it has decreased by at least 84% in the last 130 years.

James Bell, at the Rothamsted research institute, which led the research on woods, said: “With global warming one would expect woods to offer some protection for insects, a buffer against change. But we have not seen it. It’s the biggest surprise and it’s disturbing. There really is no place to hide against the effects of global warming if you are an insect in the UK”.

Another surprise was that insects and birds living on farmland are emerging later in the spring, not earlier than expected. “We can only assume that this has to do with other non-climatic factors,” Bell said. The loss of wild areas and the change in crop types could play a role, he indicated, along with the decline in food availability leading to a delay in breeding. James Pearce-Higgins, of the British Trust for Ornithology, noted in this connection: “Birds are at the top of many food chains and are sensitive to the impacts of climate change on the availability of their insect prey.”

Another separate study has found that bird populations dependent on insects for food have fallen on average by 13% across Europe between 1990 and 2015, and by as much as 28% in Denmark, where scientists have carried out a national case study. Omnivorous birds, on the other hand, did not show a similar decline.

In short, climate change is one key factor causing insect biomass collapse. Spraying of pesticides is another.

The primary research article by Bell et al., published February 2019 in the journal Global Change Biology, found that global warming has advanced the timing of biological events. Factors explaining change included the type of habitat, altitude and how far the species lives in the north. For example, aphids reproduce very quickly and can adapt quickly to temperature changes. Their first flight is now an average of 30 days earlier than it was 50 years ago. Birds, butterflies and moths appear a week or two earlier.

Bell said the changed timing was affecting agriculture, with aphids coming earlier, but potato crops being planted later due to wetter winters. This combination meant that aphids, which transmit viruses, attacked much younger plants. “Plants are just like children, with a very poorly developed immune system, so when a virus is transmitted to a young potato plant it has a much greater effect,” he explained.

Other Animals Follow the Fate of Insects

The observations so far applied to insects are also true according to some ethologists for certain animal species that are increasingly seen in cities. Wild boars are now roaming Rome, foxes are trapped in many urban areas, even bears and moose can be found outside their normal habitat.

“In fact, the phenomenon is frequent. First of all it must be explained that these animals do not generally attack humans, rather they stay away as much as possible, “says Giovanni Amori of the Institute for the study of ecosystems (Ise) of the Italian Research Council CNR. He explained: “For a correct analysis of the phenomenon, however, it is necessary to overturn what is the common point of view because it is not the animals that invade the city but it is the man who increasingly invades the habitat of these animals.”

There are many examples of such invasions. He pointed to the case of Bakersfield, California, where, many years ago, the rapid urban development impinged on the ecosystem of a small local endemic fox, whose few thousands of specimens now remaining almost all live within the city.

Many species face an anthropization of their environment, as a result of the intense urbanization of rural and wooded areas. Animals often find themselves trapped between the borders of small and large centers, Amori explained. Some species manage to adapt to this new situation, as he pointed out: ”the fox is able to build dens even in urban parks; the wild boar easily finds in the city important quantities of food. And the seagulls manage to survive in any environment. But there are also species incapable of adapting to which, due to urban expansion, migrate or gradually disappear from areas where they used to live.”

From insects to animals to ecological collapse. Whose fault?

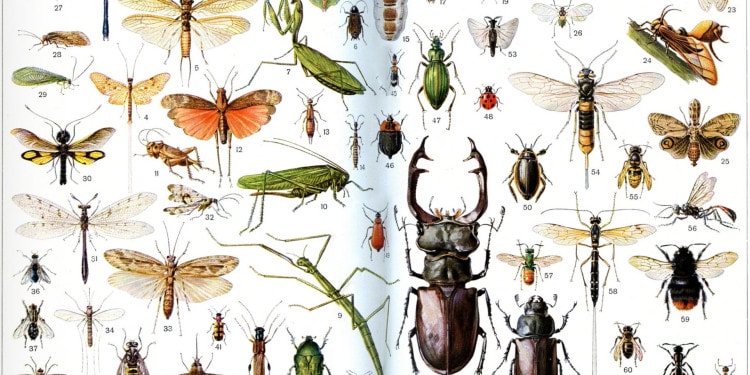

Featured Image: Insects in Brockhaus, 1937 (German table) Source: Impakter Italia