Since time immemorial, Indigenous communities have acted as caretakers of mother nature, protecting land, conserving biodiversity and passing down traditional knowledge that can help us better understand the environment and its needs. Today, Indigenous resistance has been integral in keeping the world in line with climate targets.

Taking conservative measures, a recent study has revealed that victorious and ongoing Indigenous resistance in America and Canada has prevented the emissions of 1.587 billion metric tons CO2. That sum totals 24% of annual emissions from the two countries.

To put it into perspective, 1.587 billion metric tons is roughly equivalent to the pollution produced by 400 new coal-fired power plants, more than are operating in Canada and the U.S. at the time of writing. It’s also equivalent to 345 million passenger vehicles, again more than all vehicles on the road in the two countries.

The report, jointly published by the Indigenous Environmental Network and Oil Change International, actually underestimates the influence of Indigenous resistance as it focuses on the largest and most iconic projects whilst excluding some other major projects to avoid potential double counting.

The colossal achievements were won through physical demonstrations, legal challenges and shifting public perception. Focusing on just 21 fossil fuel projects, the report details the persistence and ingenuity of Indigenous communities as they have fought to defend their rights and the scarce resources they have been left with after centuries of colonisation.

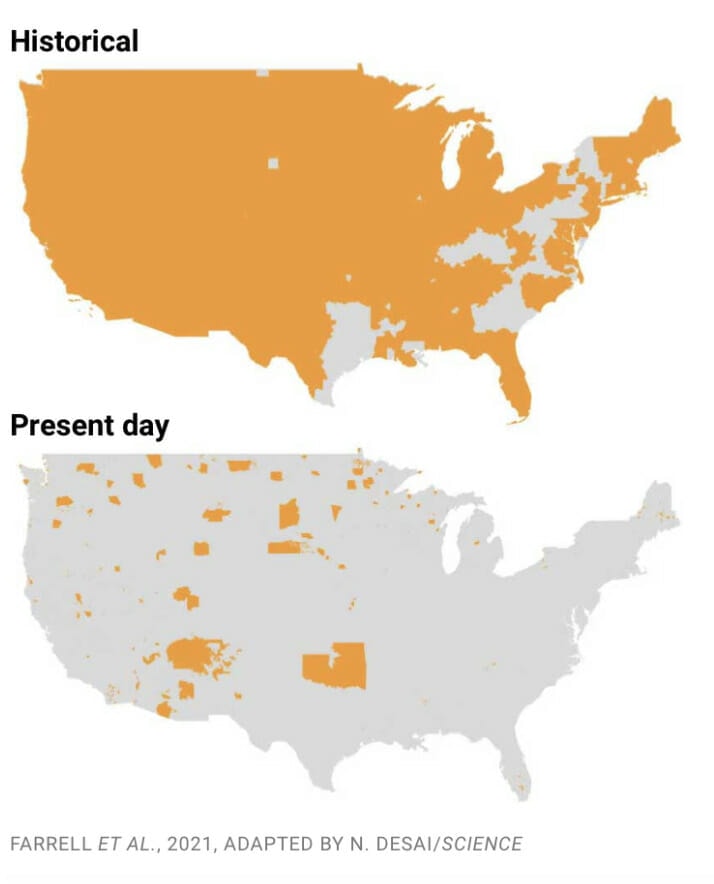

Indigenous People across the United States have lost 98.9% of their historical lands, and almost half have no recognised land today. Colonisation not only dispossessed Indigenous communities of their land, it often forcibly displaced them to land that was less valuable and currently faces more risk from climate change. “It’s not correct to talk about ‘historical’ colonialism” as if it belongs only in the past, says Kyle Whyte, co-author of the report revealing the catastrophic land dispossession.

As Whyte writes, “Colonialism and land dispossession are present factors that increase vulnerability and create economic challenges for tribes.”

Indigenous communities face higher risk from crises. The extreme heat many communities face is pushing Indigenous People into poverty and resultantly into urban areas, further eroding Indigenous culture and language.

You’re disconnecting their umbilical cord — their tie to the land, and to the elders

-Nikki Cooley, co-manager of the Tribes & Climate Change Program at Northern Arizona University, told the New York Times.

As the climate crisis increasingly existentially threatens Indigenous communities, they receive threats for attempting to avert this crisis. Since world leaders signed the Paris Agreement in 2015, over 1,010 land and environmental rights defenders have been killed. A Global Witness report found that four environmental defenders are being killed every week and this is an underestimate.

Related Articles: I Joined Native American Tribes Pipeline Protests | The Con-Game of Canada’s Oil Pipeline Crisis

The fight against the Dakota Access Pipeline

Indigenous resistance against the Dakota Access Pipeline began in early 2016. The pipeline was set to transport some 470,000 barrels of crude oil every day, whilst representing a threat to water resources, treaty rights and sacred cultural sites. Indigenous resistance to the pipeline garnered support from roughly 10,000 demonstrators at its peak.

The violence inflicted upon Indigenous defenders caught public attention as it became clear that local officials used military tactics and hired a mercenary private contractor, TigerSwan. TigerSwan described peaceful gatherings as “jihadist” and “terrorist,” responding with military-grade weapons and tactics. Water protectors were arbitrarily arrested and harassed, physically assaulted, attacked by dogs as well as water cannons in freezing conditions.

During the protests, two Indigenous women lost their eyes due to tear gas canisters and one non-Indigenous supporter had to have her arm amputated. Hundreds were left with arrests on their permanent records, a trend seen across America as over 35 states have enacted anti-protest laws.

Indigenous resistance should not have required such sacrifices nor been quashed so brutally. The international standard of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is central to Indigenous resistance and is enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

FPIC allows Indigenous communities to grant or withhold permission to projects that may affect them or their territories. However, it is seldom implemented properly. The modus operandi in the U.S. and Canada is to “consult” with Indigenous groups. This often doesn’t take place until construction has already started, but even if it does, consultation is categorically distinct to consent and often does not recognise or follow through with the wishes of Indigenous communities.

Indigenous resistance as a playbook for climate action

Indigenous resistance and traditions have undeniably delayed climate change and helped avert some of its worst consequences. Despite representing just 5% of the global population, Indigenous communities protect 80% of global biodiversity, an often unrecognised safeguard against a catastrophic crisis.

Through physically disrupting construction, court cases and the general protection of the environment, Indigenous resistance has directly stopped projects across the U.S and Canada that would emit 780 million metric tons of greenhouse gases every year. Today, across America and Canada, Inidigenous resistance stands between us and a potential 800 million more metric tons of greenhouse gases.

As leaders and climate experts from around the world gather in Glasgow to discuss the fate of our planet, it is clear that Indigenous resistance deserves respect, acceptance and inclusion. Together, these communities and their supporters have rapidly decreased emissions whilst their settler nation-state leaders have continued to subsidise and authorise construction and production of fossil fuel infrastructure.

Authors of the “INDIGENOUS RESISTANCE AGAINST CARBON” report hope that the data will lead to the recognition of the impact of Indigenous resistance and leadership in confronting the climate crisis and its primary drivers. They ask for settler nation-state governments to recognise and fulfill their duty to consult and obtain consent from Indigenous Peoples whilst acknowledging that the fossil fuel era cannot continue. Recognising the state of the environment, they urge:

Our climate cannot afford new oil, gas, or coal projects of any kind; phasing out existing fossil fuel infrastructure will already be a monumental challenge. Indigenous resistance to carbon is both an opportunity and an offering — now is the time to codify the need to keep fossil fuels in the ground, to safeguard both the climate and Indigenous Rights.

Furthermore, Whyte hopes that data exposing the dispossession of Indigenous land and their increased exposure to climate change will compel leaders to rectify this damage.

The emission targets with which leaders headed into COP26 put the planet on track to heat up by 2.7 degrees Celsius by the end of the century. A world that overly criminalises land defenders and protectors whilst subsidising and securing fossil fuel megaprojects doesn’t look like one we will survive. The efforts and successes of Indigenous resistance must be recognised. In fact, it should be held as a shining example of climate leadership and action in a world that has seen dangerously little.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed here by Impakter.com columnists are their own, not those of Impakter.com. — In the Featured Photo: Protesters at a Minnesota solidarity rally showing support for the protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline. Featured Photo Credit: Fibonacci Blue